Story highlights

A record 1,020 rhinos have been poached in South Africa in 2014

Veterinarians and rangers are relocating rhinos in the country's Kruger National Park

Rhinos are targeted for their horns, which are wrongly believed to have medicinal value

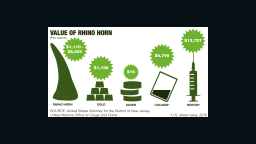

Insatiable demand in Asia means rhino horn is worth more per ounce than gold, platinum

Flying above Kruger National Park, veterinarian Peter Buss steps out onto the helicopter’s skid and aims his rifle; below him a white rhino lumbers across the South African bush. As the helicopter swoops in low, herding the animal closer to the road, Buss looks through the scope and fires a single shot.

A flash of pink on the rump is all it takes to bring the two-ton animal staggering to the ground where fellow veterinarians are ready and waiting, armed with a blindfold.

The Wildlife Veterinary Team works quickly: an oxygen tube is inserted into the subdued rhino’s nostril. Blood, hair and skin samples are taken for DNA.

Then, after another injection to partially reverse the effects of the tranquilizer, the rhino is pulled to its feet and led into a trailer for the journey to safer ground – away from this poaching hotspot along the Mozambique border, to a recently established “intensive protection zone” deeper into the park.

The team’s members are no ordinary veterinarians, but daily captures like this one are quickly becoming the norm for a team tasked with the care of Kruger’s most threatened species. They’ve already conducted more than 30 relocations since last month, and will conduct hundreds more.

They are a key part of a protection plan which has taken on even greater urgency since the country’s environmental minister announced that a record 1,020 of South Africa’s rhinos have been poached this year.

The illegal trade in rhino horn is fueled by an insatiable demand in Asia, where it is prized as a sign of wealth and believed to have medicinal value – though there’s no scientific evidence to support claims that it has healing properties.

Rhino horn is made of keratin, the same protein found in human fingernails, but it can still fetch as much as $5,550 an ounce on the black market – that’s more than the price of gold, more than the price of platinum – and roughly equivalent to the price of cocaine.

Kruger National Park, which is home to roughly 10,000 rhinos – a quarter of the world’s population – shares a 350-kilometer border with impoverished Mozambique, making it a massive target for poachers.

“We were rangers, now we’re at war,” the park’s head of anti-poaching, Major General Johan Jooste, told CNN.

But while new equipment and new technology has helped lead to a record number of poaching arrests this year, it has done little to slow the slaughter.

The general says his enemy has a nearly limitless supply of foot soldiers ready to cross the border and risk it all for small slice of the profit: last month alone, 600 poachers infiltrated the park from Mozambique.

“Once a poacher is in the park, it’s like a burglar in your home,” said Jooste, who admitted that in a park the size of Israel, military-style patrols alone will never be enough to save Kruger’s rhinos, and that much more needs to be done outside the park’s boundaries.

The intensive protection zones will at least give his rangers the chance to establish what the general calls sanctuaries within a sanctuary.

“We made the decision that we are here for the living rhino, not the dead,” Jooste explained.

There was a time when this park, famous and now targeted for its prized rhinos, had none. Several relocations, including one from 1960 to 1972 that introduced 300 rhinos, helped grow Kruger’s population, which reached its peak of 12,200 rhinos in 2010.

“This is exactly what we’ve been doing for the last 30 years,” said Markus Hofmeyr, head of veterinary services at Kruger about this latest round of relocations. “Rhinos have recovered before.”

Slaughtered for a horn that for millennia has been its first line of defense, conservationists are now counting on the rhino’s extreme adaptability to save it from extinction.