Story highlights

New study finds odd or changeable work hours linked to impaired cognitive abilities

Working antisocial hours for more than a decade ages the brain by 6.5 years, it says

The decline in cognitive abilities can be reversed if shift work stops -- but it takes time

The researchers warn such impairment "may have important safety consequences"

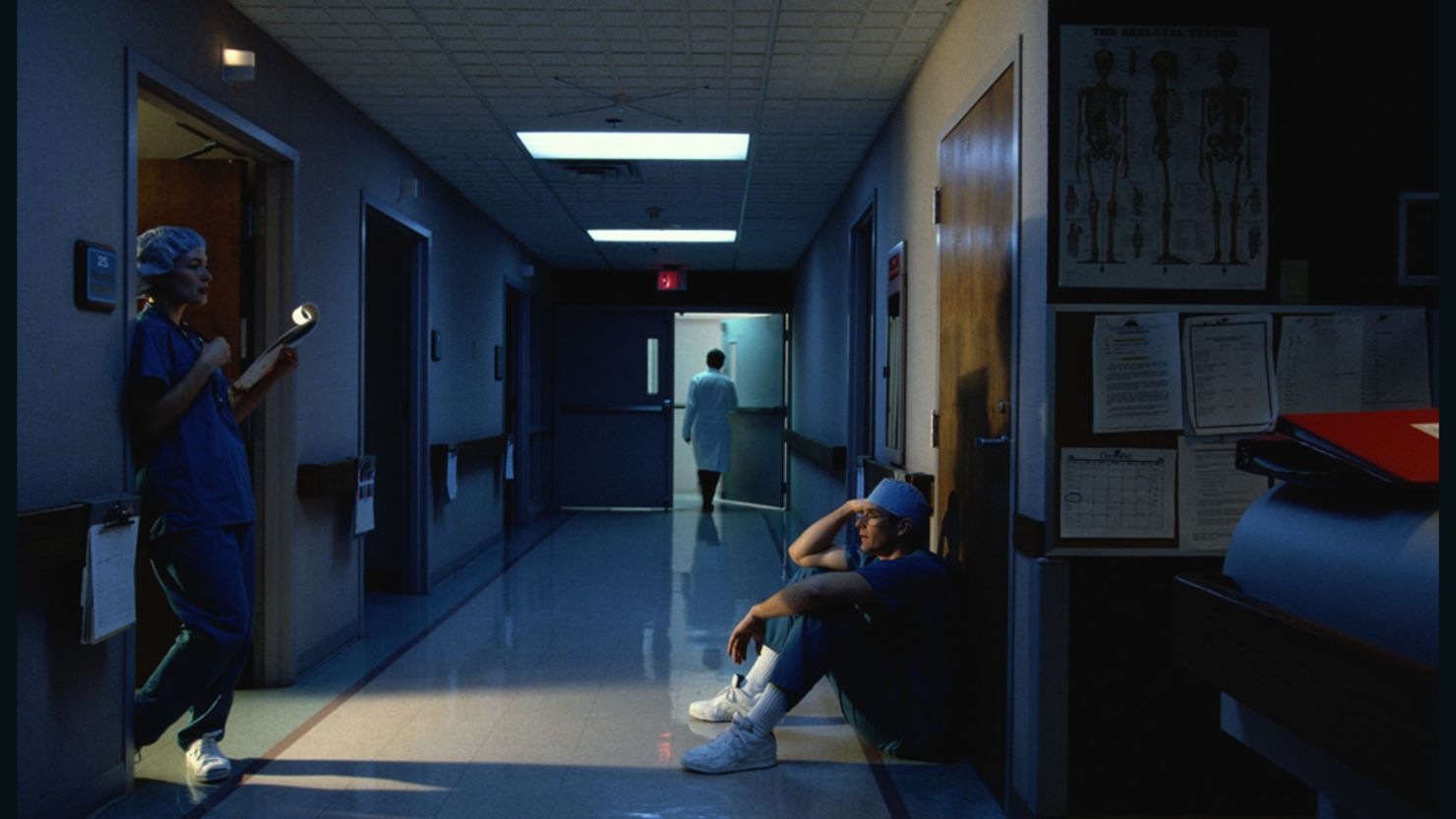

It’s not the news that any shift worker wants to hear. Not only is working irregular hours bad for your social life and likely your health, but it has a chronic effect on your ability to think, a new study has found.

The study, published in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine, looked at the long-term impact on people’s cognitive abilities of working at odd hours or with frequently changing shifts.

Researchers in France and the United Kingdom followed employed and retired workers in southern France – some of whom had never worked shifts, while others had worked them for years – over the course of a decade.

They found that shift work was associated with impaired cognition, and the impairment was worse in those who had done it for longer.

The impact was particularly marked in those who had worked abnormal hours for more than 10 years – with a loss in intellectual abilities equivalent to the brain having aged 6.5 years.

The only encouraging finding for shift workers is that the decline can be reversed by a switch to regular hours. The bad news? It takes at least five years, the findings suggest, except for processing speeds.

Rotating hours

The authors say their research is the first published study into the reversibility of the chronic impact of shift work on the brain after the shift work finishes.

For the study, the participants were asked to carry out cognitive tests intended to assess long- and short-term memory, processing speeds and overall cognitive ability on three occasions, in 1996, 2001 and 2006.

Just under half of the sample, 1,484 people, had worked shifts for at least 50 days of the year.

Participants were aged exactly 32, 42, 52 and 62 at the time of the first set of tests. In all, just under 2,000 people were assessed at all three time points.

Around a fifth of those in work and a similar proportion of those who had retired had worked a shift pattern that rotated between mornings, afternoons, and nights.

Daylight may improve office workers’ health

Normal sleep a ‘privilege’ for night workers

Circadian rhythms

The researchers, from the University of Swansea and the University of Toulouse, say this is an observational study so no definitive conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect.

However, they suggest that disruption to the body clock could “generate physiological stressors, which may in turn affect the functioning of the brain.”

Humans are wired to sleep at night by their circadian rhythm, a 24-hour cycle that brings about physical, mental and behavioral changes in the body. The circadian rhythm affects sleep cycles, hormone releases, body temperature and various processes. Besides the intellectual impact, disrupting it has been associated with health problems including ulcers, heart disease and breast cancer.

Other research has also linked vitamin D deficiency caused by reduced exposure to daylight to poorer thinking skills, the researchers say.

“The cognitive impairment observed in the present study may have important safety consequences not only for the individuals concerned, but also for society as a whole, given the increasing number of jobs in high hazard situations that are performed at night,” the researchers warn.

At the very least, the findings suggest that monitoring the health of people who have worked shift patterns for 10 years would be worthwhile, they say.

It’s a message that merits attention.

It has been remarked that accidents tend to happen late in the night or in the early morning – as with the Three Mile Island disaster in 1979 and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.