Story highlights

Hollywood studios agreed to movie self-censorship from '30s to '60s under Production Code

Censorship collapsed in wake of "Virginia Woolf," "Blow-Up" and "Bonnie and Clyde"

Led by Jack Valenti, studios and theater owners backed system rating movies in 1968

Movies go by system today despite criticism that ratings inconsistent, easier on violence

It was a “three-piss” movie.

That was studio chief Jack Warner’s review of “Bonnie and Clyde” when he first screened it in 1967. Early reaction from influential critics decrying its violence wasn’t much better.

Making “Bonnie and Clyde” would have been impossible for Warner Bros. a few years earlier. Its portrayal of attractive young killers would have collided with the censorship code, which demanded “the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.”

But Hollywood was undergoing a revolution as social change swept the country in the 1960s. The youth-oriented “Bonnie and Clyde” was one of the final nails in the coffin of the Production Code, or Hays Code, the self-censorship that had ruled American movies for more than 30 years. The industry would soon ditch the strict regulations and adopt ratings that allowed filmmakers more freedom and let parents decide which films their children could see.

The decade was ripe for the ratings system, according to Joan Graves, current head of the movie ratings board. “There was upheaval everywhere. It was a complete reversal of rules,” she says.

The ’60s conjure up images of sex, violence, drugs, and political and social revolt, but few American films then could reflect this tumult.

“The old ’50s Doris Day/Rock Hudson comedies … were thought of as fluffy and too unrealistic. The climate was right for it,” Graves says.

5 surprising things that TV in the ’60s changed

The major studios and theater owners in 1968 finally agreed to the voluntary rating system, which originally classified movies into four categories. Anyone who has come of age since the ’60s has grown up with movie ratings — initially G, M (later PG), R and X and now G, PG, PG-13, R and NC-17. Today, they still determine the way in which movies are released and marketed as well as give parents the responsibility for their children’s viewing habits.

Ratings opened the door to a wider variety of films, says Jon Lewis, a film studies professor at Oregon State University and author of “Hollywood v. Hardcore: How the Struggle Over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry.”

Eventually, the studios came up with “a new range of products that would have been unthinkable before 1968.”

With “Bonnie and Clyde,” Warner, the aging mogul, showed his disdain and lack of interest for what he considered a gangster movie retread with frequent trips to the toilet, according to the Mark Harris book “Pictures at a Revolution.” But younger moviegoers discovered something new in this ’60s take on ‘30s outlaws.

Both it and “The Graduate” appealed to young audiences, precisely what the ratings system intended to help revive the industry, Lewis says.

These two films that captured the decade’s rebellious spirit anticipated the new order.

“Their success made it clear to the studios they needed to make a change,” he says.

No ‘excessive and lustful kissing’

Movies from the Great Society still played by rules from the Great Depression.

The Production Code, ratified in 1930 and strictly enforced by 1934, forbid “excessive and lustful kissing,” “sex perversion,” “miscegenation,” profanity and “indecent or undue exposure,” among other things.

The studios agreed to these rules to ensure religious groups or local and state censor boards didn’t interfere. The studios also owned theaters, so they wouldn’t show an independent film lacking code approval. But once the studios had to sell off their theaters after a Supreme Court antitrust decision in 1948, they could no longer control what could be shown.

TV in 1960s vs. today: Times have changed, right?

By the mid-’60s, the American movie industry faced a dilemma: It was losing audiences to television and to foreign films with more realistic views on sex.

“Movies had to compete. (The studios) had to create products that appealed to a much wider audience,” Lewis says.

The crisis over the out-of-date code came to a head in 1966 as Jack Valenti, a special assistant to President Lyndon B. Johnson and a former advertising and PR exec, took the reins of the Motion Picture Association of America, or MPAA, a trade group made up of the big studios.

“Within a year into my new duties, I was almost drowned by a river of controversy I had not anticipated that tested me as nothing before or since,” Valenti wrote in his memoir, “This Time, This Place: My Life in War, the White House, and Hollywood.”

Before his arrival, “The Pawnbroker” became the first code-approved movie with nude scenes. In the Sidney Lumet film, a Nazi concentration camp survivor (Rod Steiger) recalls the horrors of his wife being stripped naked in the camp in a flashback while a desperate prostitute exposes her breasts to him.

On appeal, “The Pawnbroker” received an exemption to the code as “a special and unique” case that shouldn’t be viewed as “setting a precedent.” The unraveling had begun.

‘Blow-Up’ over censorship

Valenti first had to tackle what he would later call the Fort Sumter in the war over censorship – “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

The adaptation of the Edward Albee play was full of profanity that had never been heard before in an American movie, including “screw you” and “hump the hostess.” In this bruising drama, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton square off as a middle-aged academic couple who invite a young professor and his wife over for an evening of “fun and games.”

Director Mike Nichols didn’t film any cover shots with less salty language, so the movie would be difficult to tone down. Valenti negotiated with Jack Warner for three hours.

“At the end of the meeting, Jack and I had agreed that we would leave in ‘hump the hostess’ but take out three instances of ‘screw you’ and leave one intact,” Valenti recalled in his memoir. “Afterward, I told (MPAA general counsel Louis) Nizer I was thoroughly uncomfortable with the meeting. It seemed silly, even absurd, that grown men could be spending their time on such a puerile discussion.”

Besides watering down language, Warner Bros. agreed the movie would carry a warning that no one under 18 would be admitted without an adult, a precursor to the R rating.

But Valenti recognized that “throwing the Hays Code over the side and replacing it with the warning ‘For Mature Audiences’ was not going to cut it. It was too little and very late.”

MGM soon bypassed the code entirely with “Blow-Up,” distributed through a subsidiary. Michelangelo Antonioni’s film about “swinging” London flouted the censors with nudity, sex and drug use, including a photographer’s romp with two nude teen girls.

Premier Productions was established for “Blow-Up’s” release; code restrictions didn’t apply since it wasn’t an MPAA member like MGM.

“It sent a message that the studios were so fed up they were willing to set up a make-believe subsidiary,” says Lewis, the Oregon State professor.

By that time, “the studios are not on board anymore.”

Ratings system takes shape

Ratings in 1968

MOVIE RATINGS IN 1968G – Suggested for general audiencesM* – Suggested for mature audiences (adults and mature young people)R** – Restricted (Persons under 16 not admitted unless accompanied by a parent or adult guardian.)X** – (Persons under 16 not admitted.)

Fearing the possibility of government action, Valenti became determined to scuttle the code.

His solution was a classification plan, geared toward parents, that the studios had resisted because they thought it would limit audiences.

“The idea was to set up a voluntary movie ratings system, giving advance cautionary information to parents so they could make better decisions about the movies their children went to see,” Valenti wrote in his memoir.

It took Valenti two years to sell the concept, first to industry groups and then to religious organizations, according to Graves, chairwoman of the ratings board, the Classification and Rating Administration.

Movie ratings today

MOVIE RATINGS TODAYG – General audiences (All ages admitted.)PG – Parental guidance suggested (Some material may not be suitable for children.)PG-13 – Parents strongly cautioned (Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13.)R – Restricted (Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian.)NC-17 – No one 17 and under admitted.

Its success was guaranteed when the National Association of Theatre Owners agreed to enforce the ratings, she says. “That convinced people that it would have teeth.”

“They are the first line of defense,” Graves says. “They not only prefer rated films but enforce (them).”

The system went into effect November 1, 1968. Filmmakers could appeal to an industry panel if they objected to the board’s decisions. Critics over the years have contended ratings are arbitrary and tend to be more lenient on violence and tougher on sex and language.

But Valenti always defended his baby.

“It has lived a long, full, useful, and sometimes controversial life,” he wrote in his memoir, published shortly after his 2007 death. “… Nothing lasts very long in this brutal, explosive, unpredictable marketplace unless it is conferring some benefit on the people it aims to serve – in this instance, the parents of America.”

The ratings system is not perfect, says Matthew Bernstein, chairman of Emory University’s Department of Film and Media Studies, arguing it can have the effect of censorship if filmmakers have to make cuts for a certain rating.

But he says it’s important to note the difference between such a system and the old code.

“Classification is different from censorship by its nature. It’s one thing to say you can’t see a film at all,” says Bernstein, also editor of “Controlling Hollywood: Censorship and Regulation in the Studio Era.”

Different kinds ofmovies for a new Hollywood

With the code gone, the decade’s end saw a flood of adult-oriented films. The themes of violence, sex and outsiderness that “Bonnie and Clyde” explored were prevalent in 1969, the first full year of ratings.

In “Midnight Cowboy,” a Texan (Jon Voight) dreams of becoming a hustler in New York and servicing rich women. But he ends up working 42nd Street. Impoverished, he has only one friend, an ill con man (Dustin Hoffman).

“It’s a film about – not a gay prostitute – but he engages in gay sex acts for money,” says Lewis, the Oregon State professor. “I can’t even imagine suggesting that pre-1968.”

Four years after “The Sound of Music” captured the top Oscar, “Midnight Cowboy” became the first X-rated movie to win best picture, although it was later rated R. (Initially, X didn’t carry such a stigma, but it became associated with porn films after the MPAA didn’t copyright it. NC-17 replaced X in 1990.)

“The Wild Bunch” has minimal sex but lots of violence. Whereas “Bonnie and Clyde” faced ambush in a quick, shocking hail of bullets, this R-rated Western comes with bookends of gory shootouts that seem to last forever.

Outlaws ride into a Texas border town posing as soldiers to rob a railroad office and square off against bounty hunters in a ferocious gunbattle.

“Ten years earlier it would have been a climactic scene in a movie,” Bernstein says. “This film begins with it and escalates further in the final shootout with machine guns.”

There, the outlaws get slaughtered in Mexico. “It challenges who’s the good guy and who’s not. You can’t really say,” Lewis says.

The violence continues in “Easy Rider,” a time capsule of late ’60s counterculture. Rednecks fire away at hippies (Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper) on a motorcycle trek in the South. A bike explodes into a ball of fire, evoking images of Vietnam.

It’s open to debate whether the industry was responding to the marketplace with these movies or reacting to changes after years of assassinations, protests and war.

The rating system wasn’t motivated by social transformation, but by money, Lewis contends. “It’s wrong to think of the new ratings as going hand in hand with the Age of Aquarius,” he says, adding that “it was a necessary business move. Within four or five years, Hollywood turned around, and it hasn’t had a bad year since.”

But these movies weren’t made in a vacuum.

“The studios wouldn’t have made these if they hadn’t determined that’s where the audience was,” Bernstein says. “Business informs these decisions. But they also happen in a social context.”

Were ratings a marketing ploy? A response to a demand for greater freedom? Some of both? The answer may be as ambiguous as the movies that signed off that crazy, wild decade that still fascinates and confuses us.

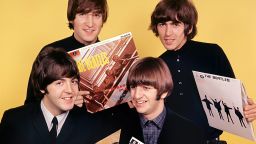

5 things to know about Beatlemania

Gene Seymour: The best summer movie ever