Editor’s Note: Robin Washington is a research scholar for the San Francisco-based think tank Be’chol Lashon. He lives in Duluth, Minnesota. He was previously the editor of the Duluth News Tribune. You can follow him on Twitter @robinbirk. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

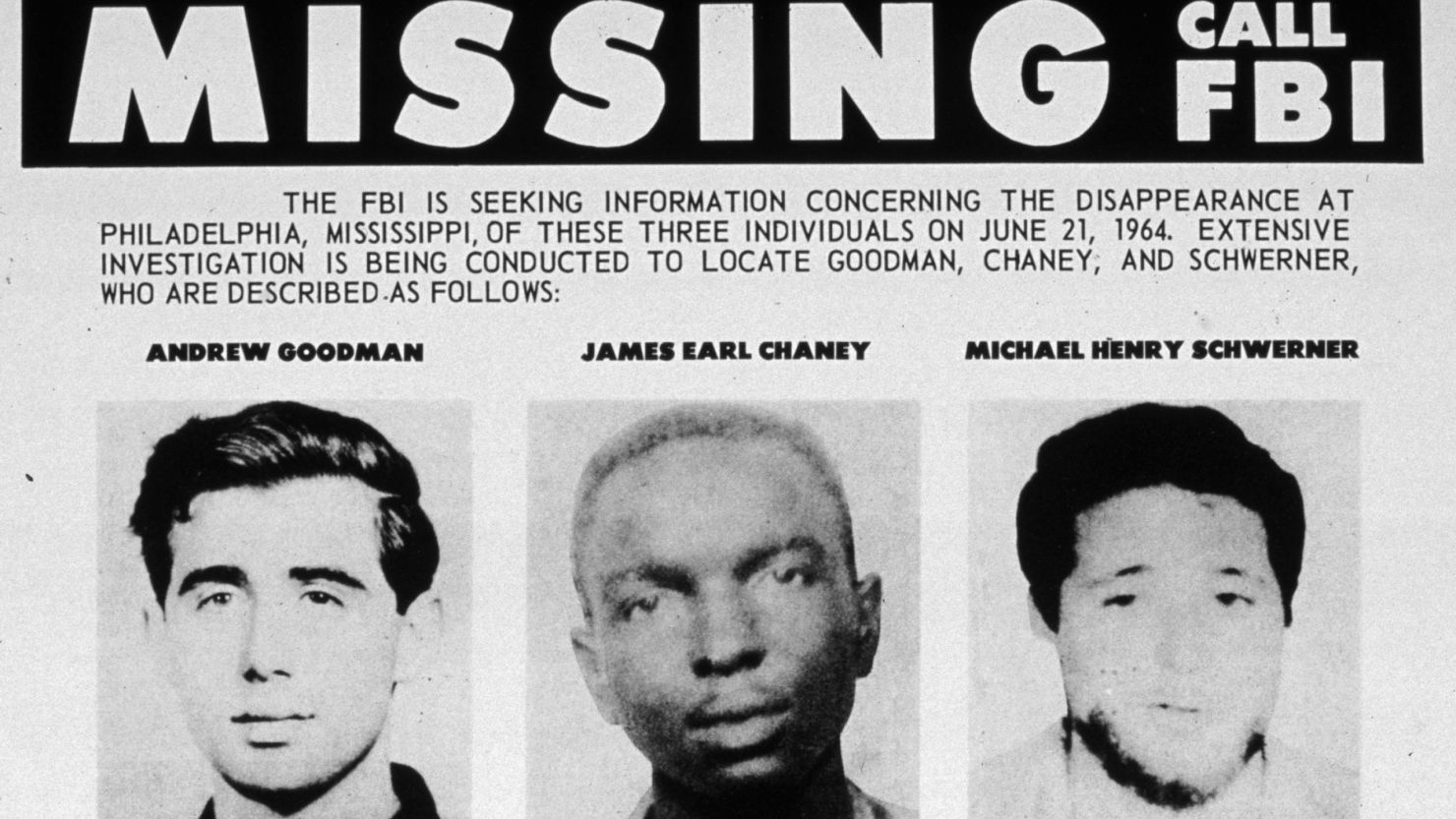

Robin Washington says 50 years after the murders in Mississippi, history repeats itself

Three young men were killed in 1964 while trying to secure voting rights for all

Today, the Supreme Court and conservative statehouses are turning back the clock

In Neshoba County, Mississippi, on the night of June 21-22, 1964, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner went missing. Their bodies would be discovered in an earthen dam 44 days later as the ultimate payment for their efforts to secure voting rights for all Americans.

Yet 50 years later, it’s as if it barely happened.

A right-leaning Supreme Court has decimated the Voting Rights Act, the very law inspired by the deaths of those three young men. Their rulings have given the OK to conservative legislatures and governors nostalgic for the Old South to reinstitute roadblocks to voting.

What happened to learning from history?

You might remember this case was the basis of the 1988 movie “Mississippi Burning,” which starred Gene Hackman as a crusading FBI agent bent on getting to the bottom of killings by the Ku Klux Klan, though it’s hardly historically accurate.

“The movie I love to hate,” Steve Schwerner, Michael’s brother, told me from New York last week. “It makes out the FBI as the hero (yet) the Civil Rights Movement felt that the FBI was the enemy and was working with local law enforcement (who were Klan members) much more than the movement.”

Chaney’s sister, Julia Moss-Chaney, also decried the portrayal of a “hero FBI.”

“Tell me about it,” she said from her home in Willingboro, New Jersey. “If all of that had been invested, it wouldn’t have taken 44 days” to find the bodies.

Or even longer if two of the missing men had not been white. Schwerner and Goodman were white and Jewish from New York. Chaney was a black Mississippian. In a bitter irony of what the three men stood for, it was the notion of white lives being more valuable than black that helped bring their deaths to national attention.

“It’s no secret that had my brother not been with Mickey Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, we would not have known anything of what had happened to him. It’s a painful reality, but it is common knowledge,” Moss-Chaney said.

Schwerner agreed.

“We wouldn’t be talking right now if it was only Jim Chaney or if it was three Mississippi black people. There were many people that had been killed in Mississippi beforehand, and with the exception of Medgar Evers never made The New York Times, never made NBC News. Nobody ever mentioned their names.”

Michael Schwerner had arrived in Mississippi earlier that spring. Teaming up with Chaney, he immediately raised the ire of the Ku Klux Klan.

“He was targeted from the moment he arrived,” Moss-Chaney said. “You know the nature of hate: ‘Let me first make sure I degrade you to the degree in my mind that you are less than human.’ There’s nothing less than human for a white man to be than a ‘n—– lover.’ Once that’s established, then anything goes.”

Goodman joined them on June 20, 1964. They were riding in a blue Ford station wagon the next day when a deputy sheriff stopped them.

“It is sad, heartbreakingly sad, that Andy’s first day in Mississippi was the last day of his life,” Moss-Chaney said, her voice going quiet.

What were they doing that so outraged the good old boys? Aside from just being black and white together, their major work was voter registration, at the time barred to black people unless they could answer impossible questions such as how many bubbles are in a bar of soap.

An FBI investigation did lead to the federal conviction of seven conspirators in the case. Mississippi didn’t get around to prosecuting the case until more than 40 years later, when Klan leader Edgar Ray Killen was convicted and sentenced to three maximum 20-year terms for the murders.

The killings fueled passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act the next year. Yet much of that progress was turned back in 2013 when the U.S. Supreme Court gutted crucial provisions of the Voting Rights Act. It followed that in April with a ruling against affirmative action efforts in higher education.

Part of the justices’ argument was that federal actions to assure equality at the ballot box have been successful, so they’re not needed anymore. But that’s like saying a car rolls well with wheels, so you can take them off. And proof that it doesn’t work is that as soon as those enforcement measures were lifted, voter restrictions returned in the form of less-than-logical Voter ID laws.

One of those allows prospective voters to present gun registration cards as acceptable proof of eligibility, but not student IDs, Attorney General Eric Holder said in December. Is that any less ridiculous or subjectively discriminatory than asking voters to count bubbles in a bar of soap?

Yes, the arc of the moral universe is long and may bend toward justice, but it also makes a couple of back flips along the way.

“We’ve certainly made some progress,” Schwerner said of where the country is now, a half century after the murders. “On a scale of 1 to 10, if you started at 1 when Brown vs. Board of Education came down in 1954, we might be at 4 now.”

For that, three men gave their lives.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.