Editor’s Note: This story contains language that some people might find offensive.

Story highlights

New documentary captures recollections of Freedom Summer civil rights veterans

Film by MacArthur "genius grant" fellow reveals clash of idealism, casual brutality

"No one felt like he was going to make it out alive," says one volunteer

One volunteer woke up every morning with a sigh, relieved that no one had murdered him in his home the night before. Another expected a bullet from a sniper whenever she strolled down the street. And one young woman was so petrified after an encounter that she urinated on herself in public.

We’ve heard about the inspirational side of the civil rights movement: the rousing marches, freedom songs and electrifying speeches. But these recollections come from a group of civil rights veterans who sound more like combat soldiers who once lived in constant terror.

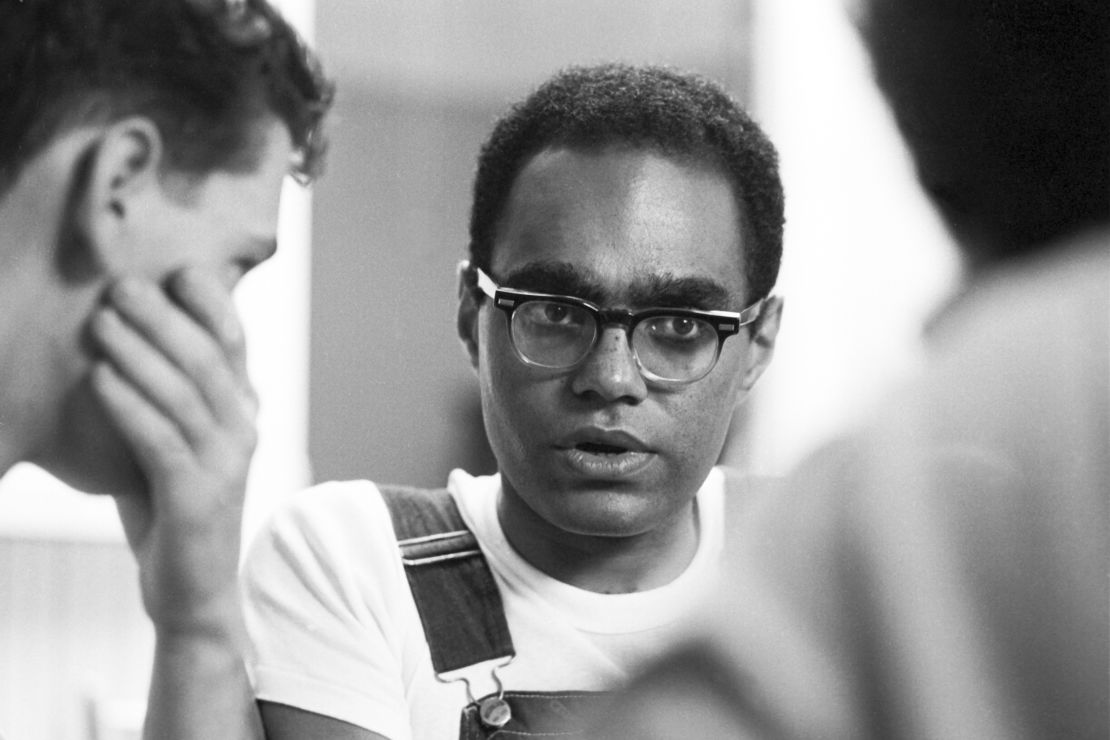

That’s part of the power of the new documentary, “Freedom Summer,” which premieres Tuesday at 9 p.m. on PBS. The “American Experience” film captures the idealism that inspired an interracial group of college students to journey to Mississippi for 10 weeks in the summer of 1964 to register African-American voters.

But it also reveals what happened when that idealism collided with the casual brutality of white Mississippians who saw Freedom Summer as a “nigger communist invasion.”

A terrifying warning

“There is no guarantee that you will get out of this summer alive; just know that,” Bob Moses, a Freedom Summer organizer, told volunteers after learning that three of their colleagues had been killed.

There have been plenty of films on the violence of segregationist Mississippi. Yet “Freedom Summer,” directed by MacArthur “genius grant” fellow Stanley Nelson, goes deeper. Nelson unearths rare film footage, interviews former segregationists, and persuades some Freedom Summer veterans to tell stories they had never before shared in public.

Still, what may be most striking about the film is not what is said but what is implied. Nelson captures the idealism of an era in America that seems as distant as covered wagons. Ordinary Americans believed they could change the world. Most Freedom Summer volunteers were only 19 or 20. They had heard President Kennedy’s challenge to “ask what you can do for your country.” They saw themselves as patriots.

“It was terrifying,” Dorothy Zellner, a former volunteer, says in the film. “But if you cared about this country and you cared about democracy, you had to go.”

The paranoia of white Mississippi

Democracy was on life support in the Mississippi of 1964. Almost half the state’s residents were black, but only 6% were registered to vote. In some counties, blacks made up 70% or more of the population but were barred from voting through a combination of literacy tests, economic intimidation – they could lose their jobs, homes or land for registering to vote – and raw violence.

It may seem odd today that the white power structure in Mississippi was willing to be so brutal just to keep people from voting. The film, though, shows that the whites’ brutality was driven by an apocalyptic fear: Black voters would drive them from office, and from the state.

Some had other fears that had nothing to do with politics. They seethed with fury after seeing white college women, who came to Mississippi for Freedom Summer, interact with black men and live with black families. One white volunteer recounted how segregationists were obsessed with interracial sex; one sheriff even asked her to describe the size of big black men’s penises.

Watch 'The Sixties'

Watch ‘The Sixties’

“We face the absolute extinction of all we hold dear,” Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett thundered during a speech at the time. “We must be strong enough to crush the enemy.”

A brush with death

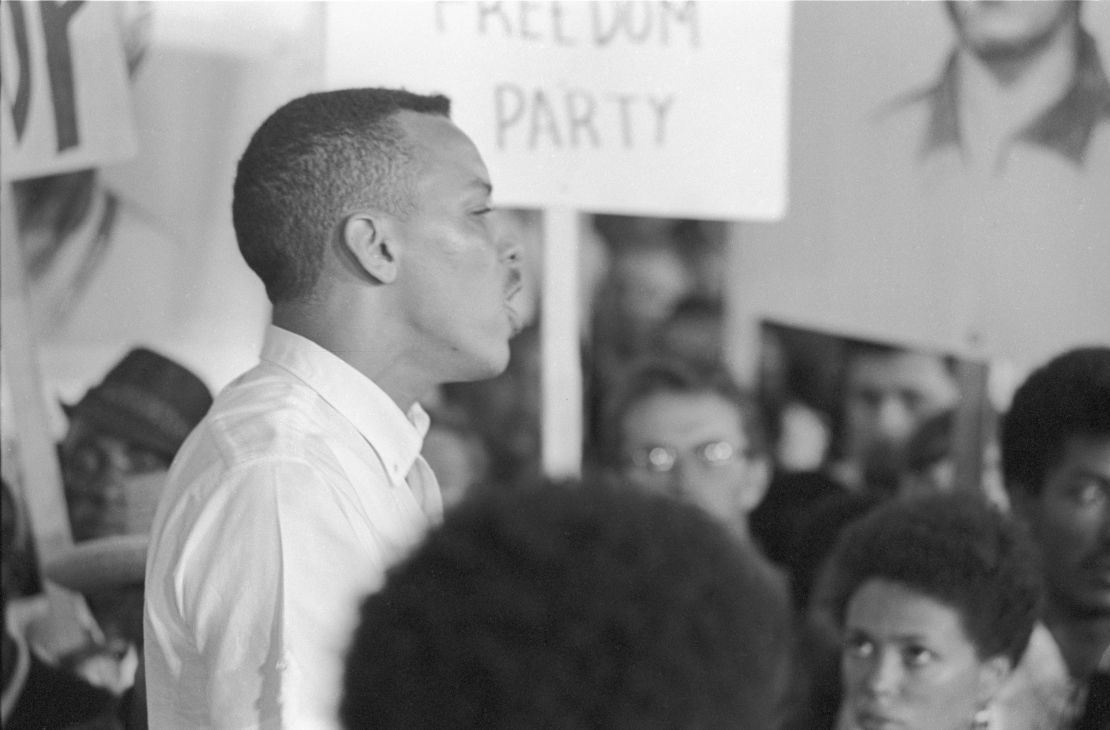

The goal of Freedom Summer, though, was to do more than register black voters. It was to empower blacks as well. The volunteers established Freedom Schools where they taught black Mississippians about black history. They established an interracial delegation to the 1964 Democratic National Convention that made a daring, nationally publicized bid to unseat Mississippi’s all-white delegation.

Some of the most powerful segments in the film, though, come during its smaller moments: A burly white sheriff viciously tries to snatch an American flag out of the hands of a small black boy leaving a courthouse; the boy bravely holds on while he’s swung like a rag doll. A former beauty queen from Mississippi recounts how family members were driven from their homes simply for having dinner with Freedom Summer volunteers. A boy photographed being educated in a ramshackle Freedom School explains how that summer changed the arc of his life; he is now a poised college professor and author.

One of the film’s most riveting moments comes when volunteer Linda Wetmore Halpern tells a story that, until then, she had been too embarrassed to share.

Halpern was walking alone on a Mississippi road one day in her summer dress when a group of laughing white men drove up, surrounded her, and told her they hadn’t killed a white girl yet.

The men grabbed her, tied a noose around her neck and tied the noose to the car. Then they started to drive, forcing her to keep up while calling her “nigger lover.” As they sped up, Halpern says, she thought she was going to die.

The men then stopped, untied the noose from the car and laughed as they drove away. Halpern stood alone in the road petrified.

“I peed all over myself,” she says, her voice shaking years later. “I just stood there and peed.”

Who were the true heroes?

Despite the courage of people like Halpern, most of the volunteers say today that the true Freedom Summer giants were the black Mississippians they worked with. Most of the students would eventually return to college, but the black residents remained to contend with the wrath of segregationists – many for the rest of their lives.

Dave Dennis, one of the Freedom Summer volunteers, remembers one such couple. He recalls seeing an elderly black man and wife pull up to a courthouse in a mule-driven buggy. The man climbed out, walked up to a set of courthouse steps ringed with white deputies, and asked where he could register to vote.

“I’m haunted by the question of what happened to them,” Dennis says. “I know they caught hell. Those to me were the heroes.”

Dennis caught hell as well. He was with Medgar Evers, the head of Mississippi’s NAACP, on the day Evers was murdered in front of his home. Dennis also knew one of the three civil rights workers who were killed that summer. At the funeral for one of the slain workers, Dennis broke down publicly while delivering remarks, shrilly shouting, “I’m tired of going to funerals.”

Dennis says some of his black colleagues from SNCC – the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which organized Freedom Summer – had worked virtually alone in Mississippi for three or four years before white volunteers joined them that summer.

“No one felt like he was going to make it out alive,” he says.

Not only did virtually all the Freedom Summer volunteers make it out of Mississippi alive, they were alive in a way they had never been before. The experience transformed them, made some of them more radical. Many of them had learned to some extent what it felt like to live as a minority. They had to stay with black families that summer and listen to their instructions to remain alive.

“They couldn’t step out of the black community,” says Nelson, director of “Freedom Summer.” “They couldn’t go downtown. They got the hateful looks that black people get all the time. They had people driving by screaming stuff at them. They got a view of race that very few white people get.”

The momentum generated by Freedom Summer led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which removed all the barriers whites had erected to discourage black voters. Last year, a conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court voted to gut a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. Since 2011, 14 states – including Mississippi – have passed voter ID laws, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a public policy institute in New York. Critics say such laws discourage minorities, the poor and elderly from voting.

Nelson, who has directed other PBS films such as “Freedom Riders,” says many of the Freedom Summer volunteers see history repeating itself with the recent Supreme Court decision.

“Everyone feels horrible about it,” Nelson says. “Everyone is so upset.”

Some Freedom Summer veterans have organized voting seminars in an effort to maintain the victories they earned 50 years ago. But some of those victories can’t be erased by any court decision.

Chris Williams, a white Freedom Summer volunteer from Vermont, said though he went South to help black Mississippians, they ended up helping him more. He witnessed acts of courage from poor black Mississippians that stay with him today. And he saw a side of America that few white people see.

“I sincerely hope that I made some small difference in moving the movement forward” he says. “But I don’t have any doubt all these years later that the person who benefited the most from my being in Mississippi was me.”