Editor’s Note: Tom Hayden writes and advocates for peace, justice and the environment. A member of the editorial board of The Nation, he is author of 18 books and has been a visiting professor at many universities. He served 18 years in the California legislature. Hayden was a founder of the Students for a Democratic Society, and the principal author, in 1962, of the group’s manifesto, the Port Huron Statement. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Shocks and jolts of 1960s transformed Tom Hayden from student advocate to radical

Early activists of '60s stayed true to belief that system could be changed from within, he says

Hayden says disillusionment grew over Vietnam, repression led to underground outside law

Most activists re-entered everyday life after decade's key battles won, he says

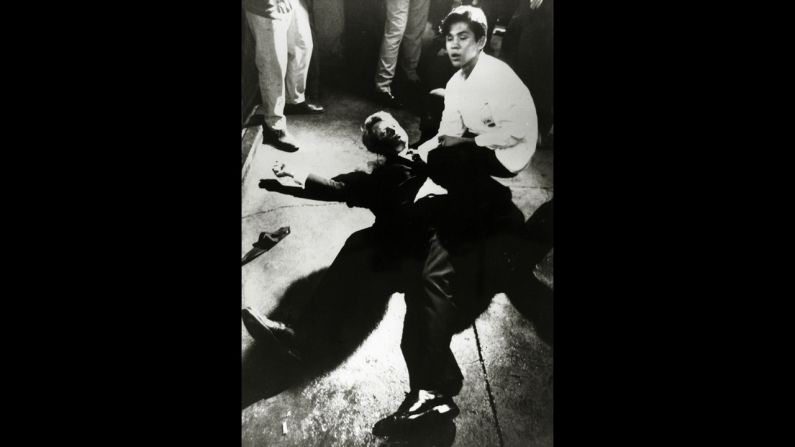

Shortly before he was murdered, Robert Kennedy was underlining this passage from Ralph Waldo Emerson:

“When you have chosen your part, abide by it, and do not try to weakly reconcile yourself with the world. … Adhere to your own act, and congratulate yourself if you have done something strange and extravagant, and broken the monotony of a decorous age.”

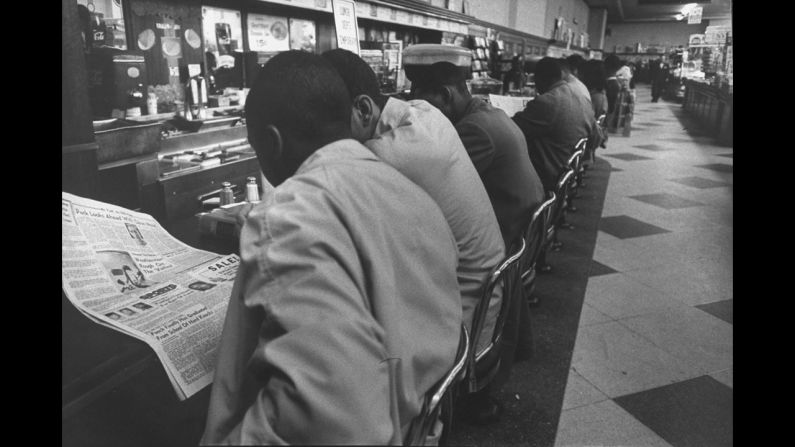

These were the questions we all asked ourselves in the tumult of the 1960s: Whether to “weakly reconcile” to the status quo of our parents’ world, or break the monotony by actions that might seem “strange and extravagant.” Like sitting quietly at a Greensboro lunch counter while frothing racists pushed cigarettes into unbent necks.

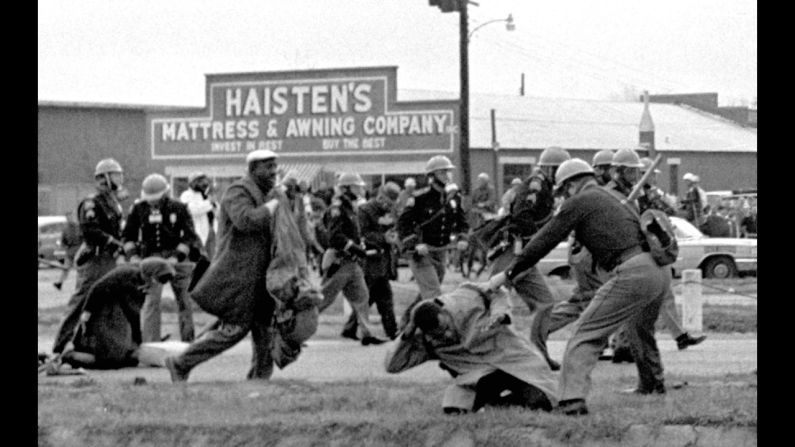

Or striking a match to our draft cards when we saw Buddhist monks burning themselves in Vietnam. Or coming out of one closet after another. Or facing baton-wielding troops driving jeeps with barbed wire toward 20-somethings at the 1968 Democratic National Convention I asked such questions in my own life back then. I grew up as a Catholic idealist whose innate curiosity drew me to investigative journalism. As a young man, I hitchhiked from Ann Arbor, Michigan, to Berkeley, California, in 1960 on the trail of the Beat Generation.

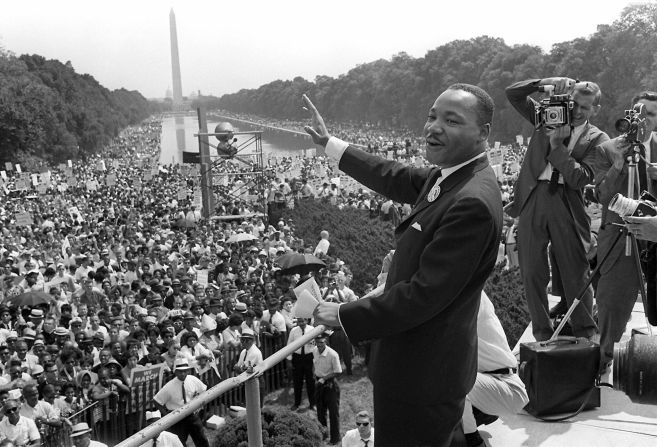

I was most inspired by those young people of my generation who found a cause worth dying for on the civil rights battlefields of the American South. I interviewed a young Martin Luther King Jr. in 1960 while he picketed the Democratic convention in Los Angeles demanding a civil rights plank. Frankly, I wanted to get a front-page story. He was so patient and logical in answering my questions that it made me consider putting down my pen for a placard. Gradually my journalism became advocacy, my advocacy turned to activism.

In 1962, I drafted the manifesto of the Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, known as the Port Huron Statement, defining young people as agents of social change and calling for participatory democracy. I was enlisted as a Freedom Rider in Georgia, then became a door-knocking community organizer in the slums of Newark, New Jersey, and for 10 years an angry opponent of the Vietnam War. In eight years, I was transformed from being a student editor advocating for the Peace Corps to a dangerous menace in the mind of the FBI.

The government responded to protests such as mine with accusations of terrorism and prosecution for conspiracy. As the repression grew, so did the length of my hair and my sympathies toward revolution.

Similar to a natural birth, the birth of the ’60s contained the joyous power of creation. And like all births, there was blood and danger. As Albert Camus wrote in “The Wager of Our Generation”:

“Yes, there was the sun and poverty. …Next the war and resistance. And, as a result, the temptation of hatred. Seeing beloved friends and relatives killed is not a schooling in generosity. The temptation of hatred had to be overcome. And I did so.”

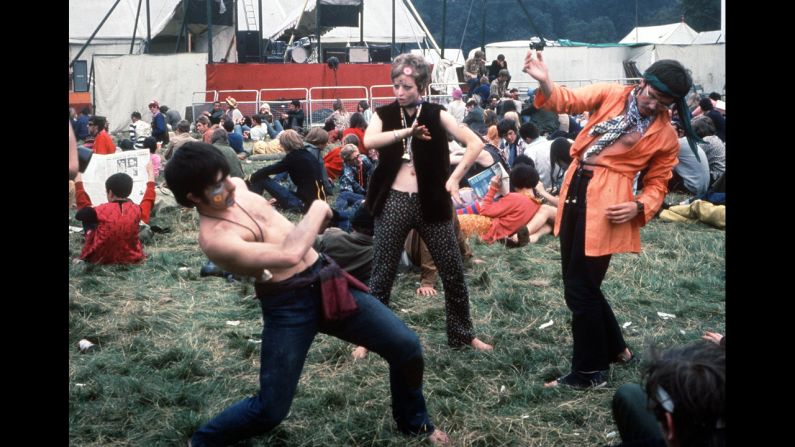

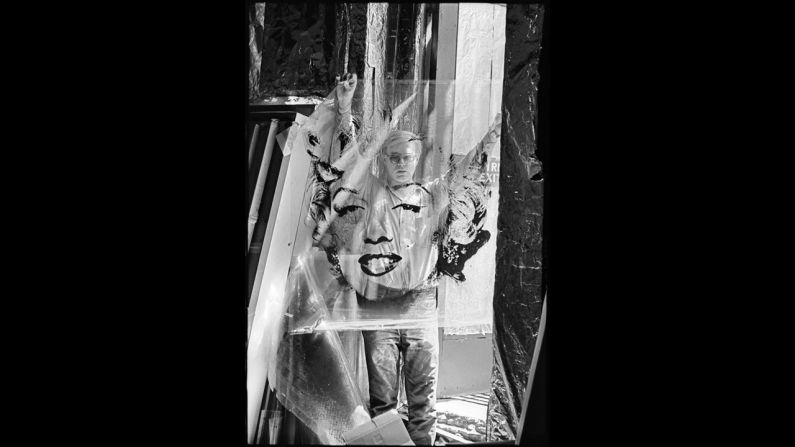

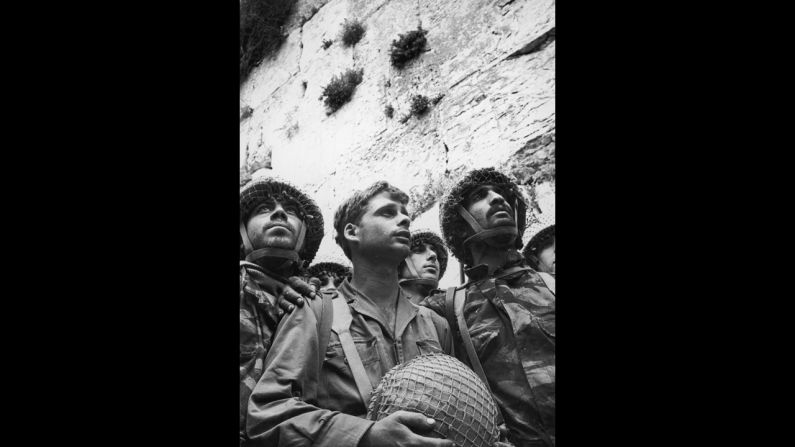

This was a social revolution led by middle-class students but propelled by “the wretched of the Earth” in places such as Cuba, Vietnam, Belfast, Selma and Oakland. The rising started without a press release and little press notice. Allen Ginsberg read “Howl” at a poetry reading in San Francisco because he, along with Jack Kerouac and now-famous others, were having trouble getting poetry published.

Neither was there any significant coverage of the February 1, 1960, sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina. The four students at the Woolworth’s counter had “no plan whatever.” The student civil rights movement simply announced itself.

Our elders’ most common response to our actions was repression and force. “Howl” and its City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti were prosecuted for obscenity in 1957. The FBI infested the campuses with thousands of agents searching for secret communists – or, it turned out, gays, lesbians, philandering professors and alcoholics among the Berkeley faculty. The white-collar Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission worked with the hooded Ku Klux Klan to terrorize people wanting to vote.

Despite these shocks and jolts, the first generation of activists in the 1960s stayed largely true to the hope that our elders were somehow mistaken, that the institutions could be reformed from within with just one more push. That hopeful pragmatism renewed itself with each new wave of protest, for example through the “Clean for Gene” volunteers tramping through the New Hampshire snow for moderate anti-war candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy in 1968.

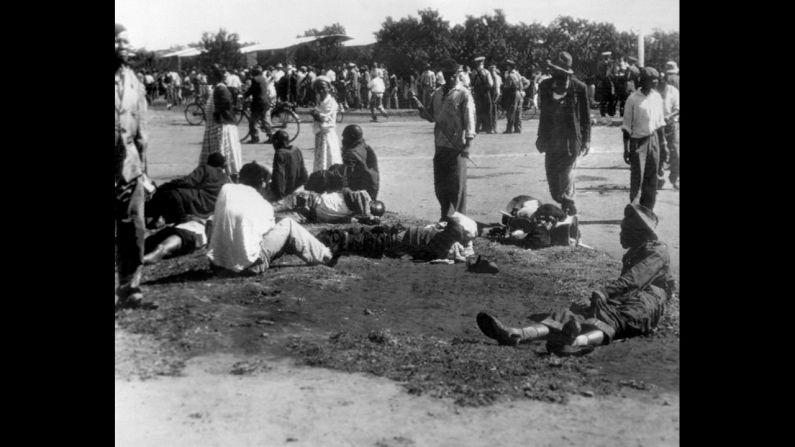

But a deeper disillusionment sank in with each assassination of an elected leader, each photo of a napalmed Vietnamese child, each body dredged from Southern swamps and bayous.

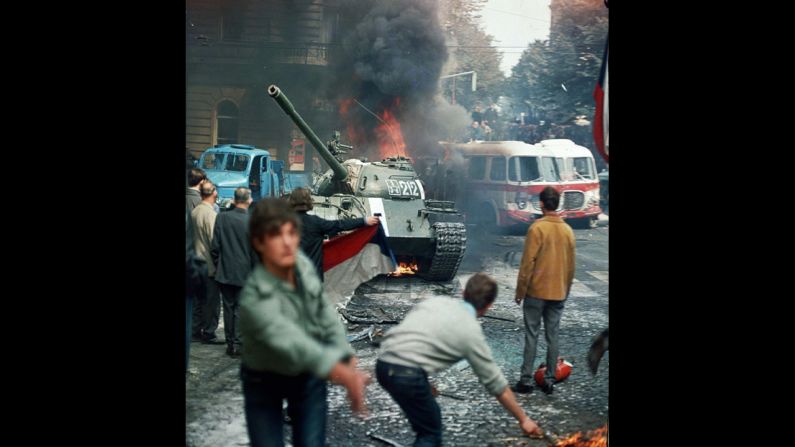

The “temptation of hatred” predicted by Camus seeped in with Vietnam. The first U.S. aircraft bombed North Vietnam in August 1964, even as some of us were burying the three civil rights workers killed in Mississippi.

A few months later, after the SDS supported Lyndon Johnson because he promised to send no “young American boys” to Southeast Asia, the President did just that. More than 100,000 were sent into combat that first year.

The Vietnam draft got young Americans’ attention like nothing before. White students in the North sensed in that moment what it was like to be a black student in the South. And it must not be forgotten today, when lying politicians are taken for granted, that this was the first time a young generation elected a president who lied about sending its own brothers to their deaths after promising not to.

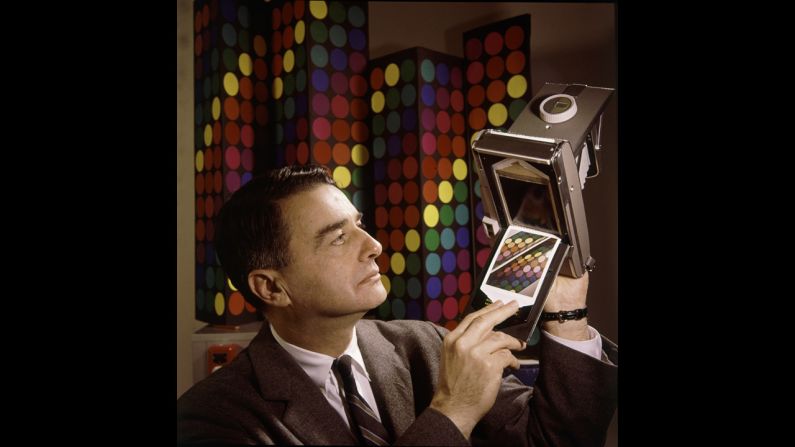

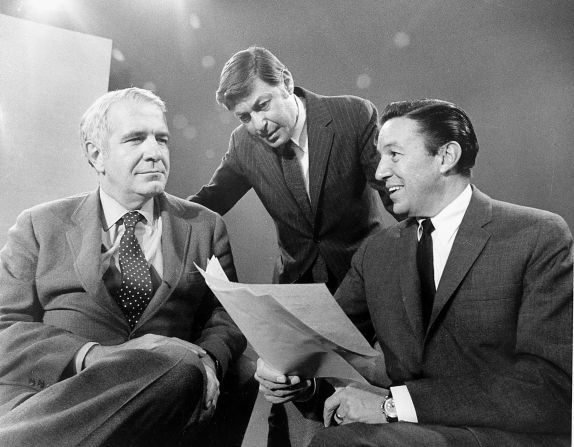

Watch ‘The Sixties’

If innocence wasn’t dead already, its headstone now read: “Died in Vietnam, 1965.”

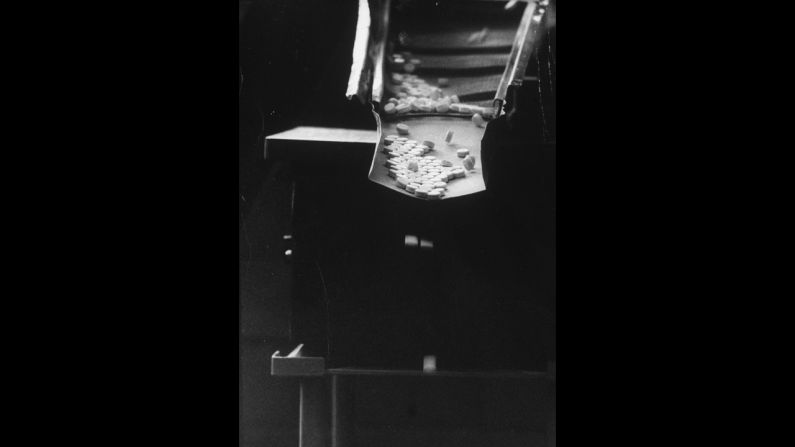

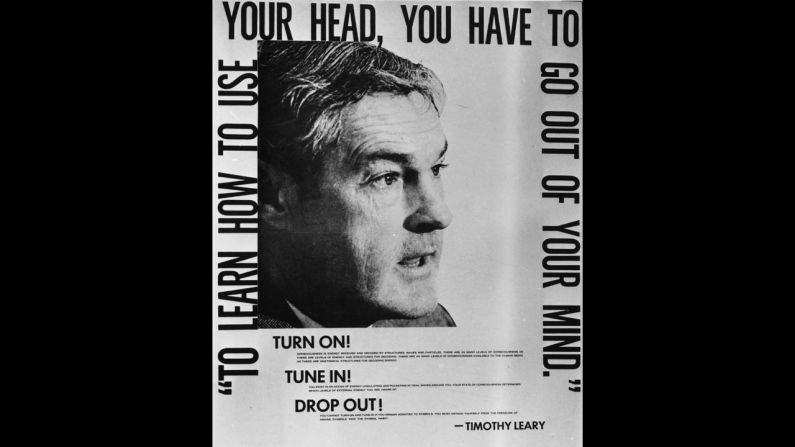

It was perhaps only accidental that the CIA began covertly distributing LSD in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco the same month that those ground troops were shipped off to Vietnam. A mistake gone out of control, it later said. “Mistake” would become the designation for one dysfunctional disaster after another, Vietnam being the greatest. There were no apologies.

The question remains: Why did so many 20-year-old students recognize that Vietnam was a mistake from the beginning – from the first campus teach-ins of March 1965 – while our liberal and conservative elders were so certain that it was a necessary, winnable and affordable war against communism? It was certainly not because the peaceniks and beatniks and women’s libbers were connected to the Communist Party. Even the CIA rejected that Cold War reasoning in an exhaustive confidential 1968 report to the President.

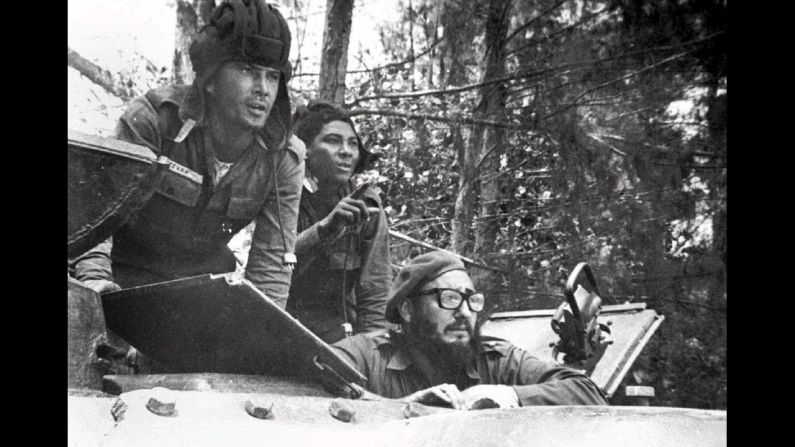

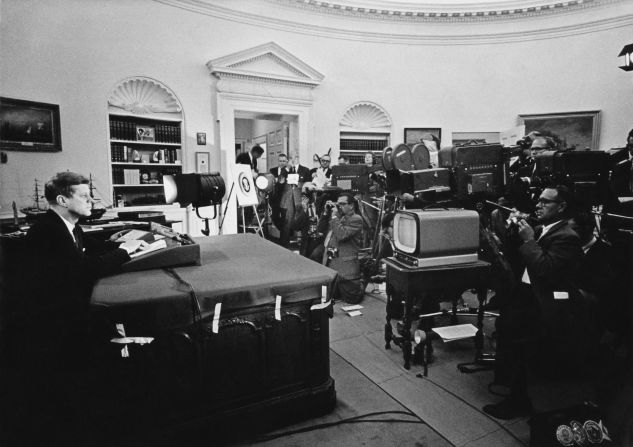

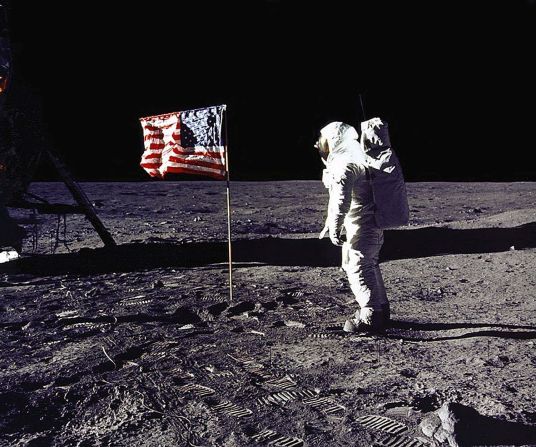

We protested because we went through a collective near-death experience when our government and Moscow came close to nuclear war over Cuba in 1962. Like Cuba, we learned that Vietnam was a proxy in the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union. We instinctively rejected the notion that the world could be divided into two superpower camps.

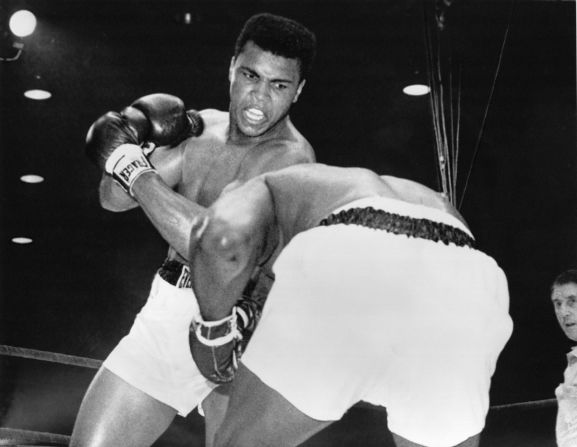

We protested because of our civil rights experience in the South, where a kind of Third World land reform movement was taking place: Those sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta looked awfully like the Vietnamese rice farmers in the Mekong Delta, inspiring our global solidarity. Muhammad Ali drew a compelling conclusion: “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

Resistance to authority grew in the streets by 1966, based more on existentialism than ideology. For those of draft age, the only choices were to serve in a dubious war, take exile in Canada or risk an indefinite prison term.

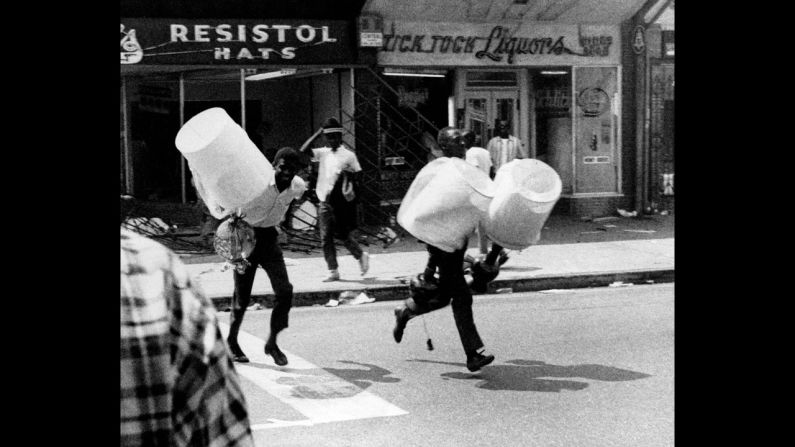

An underground grew up outside the law, including dissidents from draft evaders to Black Panthers on the run, priests and nuns, marijuana offenders and revolutionary saboteurs. The police and FBI caught few of them, and juries refused to rubber-stamp conspiracy charges in the cases of the Chicago Eight, the Catonsville Nine – Catholics, including priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan, charged after they burned several hundred draft files – and many more.

On its side, the state in the late ’60s deployed 1,500 federal Army intelligence officers to surveil 100,000 Americans; another 2,000 FBI agents were dispatched to disrupt legal organizations and “neutralize” protest leaders, myself included.

In 1969 alone, I was grazed by death three times.

First, my closest friend and co-author of the Port Huron Statement, Richard Flacks, was assaulted at his university desk in Chicago with a claw hammer and left for dead (he lived on). Second, Bay Area police used live ammunition without announcement in quelling the Berkeley People’s Park protests; I watched as they killed a young man named James Rector and permanently blinded his friend Alan Blanchard as they sat on a rooftop. Third, during the Chicago conspiracy trial, the police shot and killed two Black Panthers in their sleep; one of them, Fred Hampton, had attended the trial daily as a liaison to Panther leader Bobby Seale.

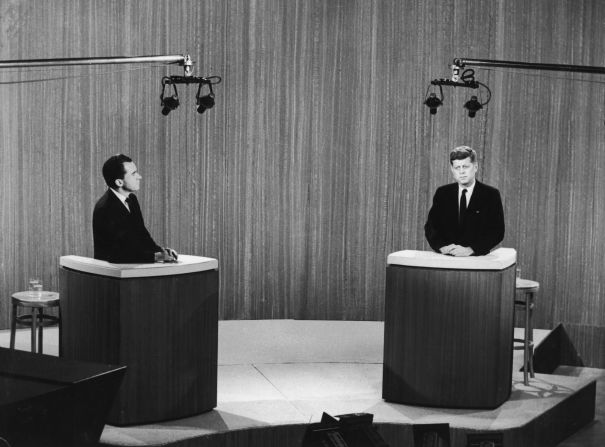

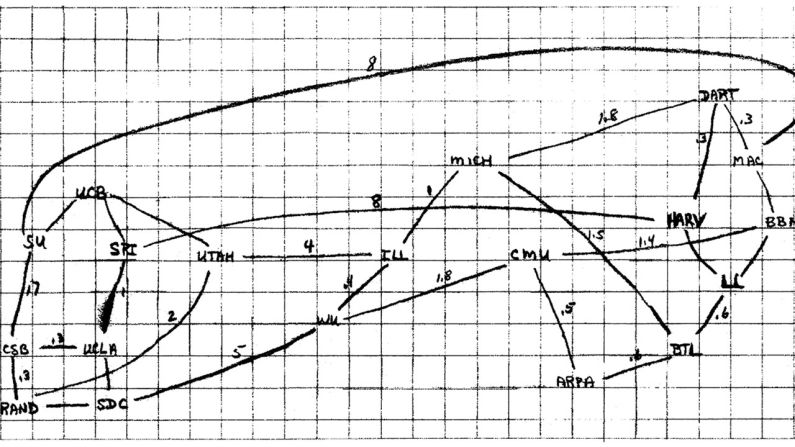

Using available data, one can chart a history of the ’60s in a rising line, starting from peaceful protest, 1959-64, then a sharply ascending trajectory toward violence (bombings, police-Panther shootouts, Weather Underground, Kent State, etc.) until 1975, when the line flattens out once again (end of the Vietnam War, fall of Richard Nixon). That line illustrates the truth of John F. Kennedy’s maxim that “those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable.”

There came a time in the ’70s when the sun surprisingly broke through the darkest storms. Public opinion – our parents’ opinion – began to loosen and shift. As late as 1969, the Gallup survey showed that 82% of our parents wanted student protesters expelled.

Estranged from my own ex-Marine father for a decade, I learned later that he started shouting at the television that Nixon was a liar. Soon the Democratic Party opened its doors to dissenters. Voting rights were implemented in the South. Jimmy Carter gave amnesty to deserters. Charges were dropped against Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo, who leaked the Pentagon Papers.

In addition to the Watergate hearings, Congress woke up and held the first hearings into CIA and FBI law-breaking. The first – and still strongest – environmental laws were passed. The Supreme Court upheld Roe v. Wade, affecting millions of our generation, participation or voting rights were expanded to more of the excluded, to farmworkers, the disabled, the 18-year-olds.

Vietnam vets mostly reconciled with Vietnam resisters around what we had in common: We had all been lied to. I entered the mainstream and was elected to serve in the California legislature for two decades despite Republican efforts to expel me. I teach at colleges today, where the students don’t know me, unless their parents clue them in.

The ’60s ended not because we “grew up,” or because we were effectively repressed, but because we won most of the crucial battles that had mobilized so many for so long. When the movement tides receded, most of us quietly re-entered everyday life in a culture we had changed irreversibly. Despite many premature requiems for the ‘60s, the decade continues to live as legacy.