Story highlights

A new study claims the ruins at Petra, Jordan were built to align with the sun during the solstices and equinoxes

Despite the breadth of the ruins, only 85% have ever been excavated

Little is known about the function of many of Petra's structures

The study's leader hopes his findings will shed new light on how Petra functioned

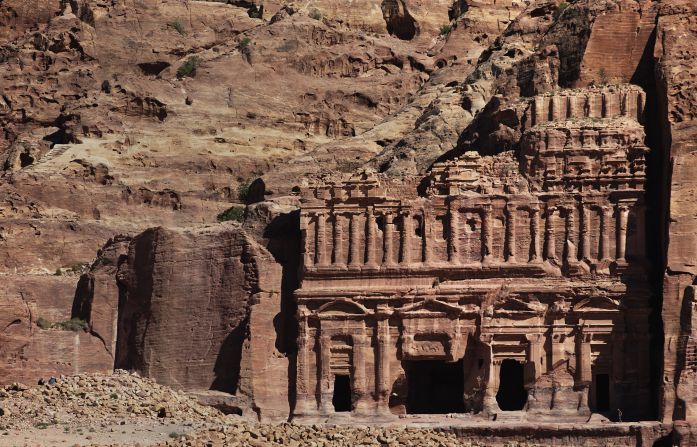

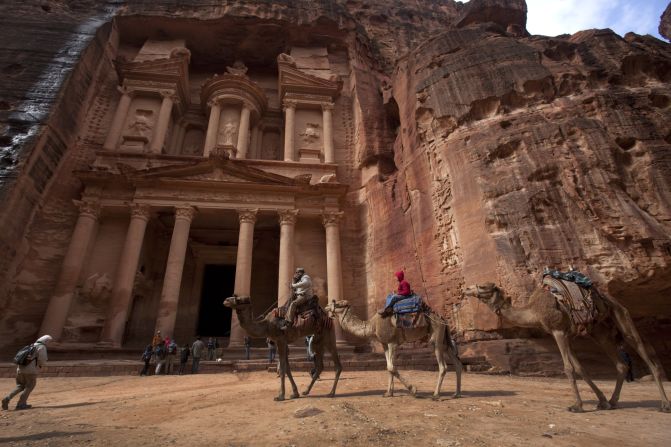

Few ancient civilizations have left an architectural footprint quite as indelible as the Nabateans did in Petra, southern Jordan.

Majestic temples, burial chambers and homes still stand, carved around 2,300 years ago from the rose-hued landscape.

Logic would dictate that the relics strewn throughout the 2.8 million square feet of Petra Archaeological Park would provide historians with a bounty of information about the ancient culture.

In fact, surprisingly little is known about ancient Nabatean life and traditions. An estimated 85% of the area has never been excavated, and there is precious little in the way of written records.

“I don’t think we really understand what significance some of these structures truly had,” says Megan Perry, an associate professor at East Carolina University’s department of anthropology.

Recently, a team of archaeoastronomers sought to gain some insight into the function of these ancient structures by measuring their celestial alignments. Their findings, which were published in the Nexus Network Journal, suggests that the Nabateans purposefully built Petra’s most sacred structures to align or light-up during celestial phenomena, including the summer and winter solstices and the equinoxes.

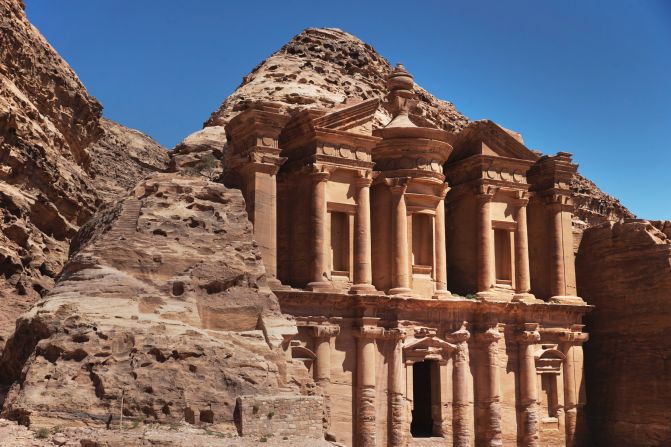

Juan Antonio Belmonte, the study’s leader at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC), notes that the effect is particularly stunning at Ad Deir, also known as The Monastery – one of Petra’s most visited attractions.

“The lighting is spectacular; the sun setting through the gate perfectly illuminates the sacred areas of the deep interior,” he says.

“Apart from the beauty of the situation itself, the effect – which would have been observable only a week or so before and after the winter solstice – also gives you information about the purpose of the building.”

Indeed, there’s been much debate in the archeology community over the exact function of Ad Deir. Why was it built? Was it a tomb? A temple? Prior to Belmonte’s study, there haven’t been any clear answers.

“With such an alignment, it’s now clear that it was certainly a temple with an astral religious character,” says Belmonte.

“This can help us understand the religious beliefs of the Nabateans, and also their way of controlling time. It shows they could monitor the lunar calendar by solar and lunar observation. We’re really finding a lot of utility in these kind of measurements,” he adds.

Perry, who was not involved in the study, but who co-heads The Petra North Ridge Project, says that while she finds the findings plausible, she’s not entirely convinced by the methodology employed.

“I think the idea that the Nabateans could have done this is actually not that surprising; it sort of goes along with other aspects of their religion, and potentially their understanding of place and space,” she says.

Perry has spent a lot of time studying the layout of monuments in Petra for clues as to whether the city was laid out organically, or – as Belmonte suggest – if it was planned.

“The tombs seem to be based on natural topography. Nothing in terms of their layout suggests a tie to any kind of solar orientation. If there was one, they’d all be facing the same way, but they surround the city and face in an infinite number of directions,” she notes.

Belmonte, who measured the alignment of over 30 Nabatean monuments, both in Petra and at other sites throughout Jordan and Israel, says his measurements are too consistent to be a coincidence.

“When you study the alignments, you produce a histogram that has a certain credibility from a statistical point of view. If this is by chance, the probability is very small,” he says.

Read: The nomadic cave dwellers of Petra