Story highlights

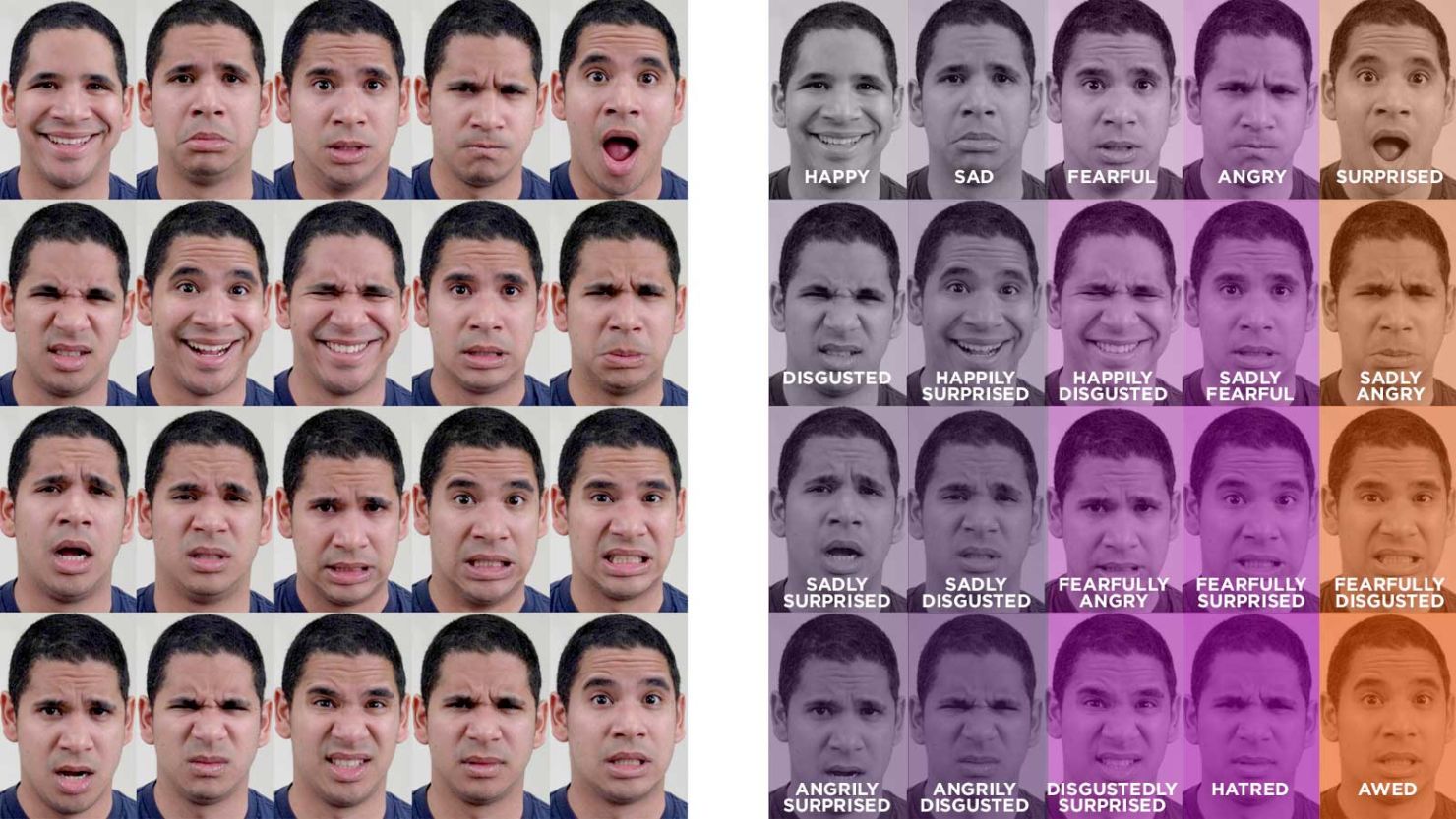

Scientists have identified 15 "compound emotions"

The emotions are expressed by combining the basic human emotions

This could impact future research on psychiatric disorders

Until recently, scientists had only identified six basic human emotions: happy, sad, fearful, angry, surprised and disgusted.

These “emotion categories,” as cognitive scientists like to call them, are defined by the facial muscles we use to express each emotion.

“The problem with that is that we cannot fully understand our cognitive system … if we do not study the full rainbow of expressions that our brain can produce,” says Aleix Martinez, an associate professor at Ohio State University.

In a new study published this week in the journal PNAS, Martinez and his colleagues have identified 15 additional “compound emotions.” These are expressed by combining the basic emotions, much like using the primary colors blue and red to create purple.

These compound emotions are all distinguishable from one another, the researchers say. For instance, “happily surprised” is very different from “fearfully surprised” or “happily disgusted.”

Scientists aren’t sure how much of our facial expression behavior is learned, and how much is innate. But they believe a large part must be biological because all humans use the same muscles to express a specific emotion. For example, when people express “happy” they raise their cheeks, part their lips and pull the corners of their mouth out.

As the two areas of study move forward, Martinez says, we will be better able to understand what happens in our brains when we feel an emotion.

Feeling glum, happy, aroused? New technology can detect your mood

Think of the brain like a computer program we’re trying to decode. In the past, when scientists tried to analyze the brain’s emotional algorithms using only six known emotions, they hit a wall. With 21 emotions, they may have better luck figuring out how it works.

The newly identified emotions could impact future research on psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia or PTSD, the study authors say, as well as research on developmental disorders like autism. It could also be used to create better human-computer interaction systems.

In Japan, for instance, engineers are trying to create a robot that can interact naturally with humans, Martinez says. Japan’s rapidly aging population is lacking young caretakers, and this robot could be a companion to the elderly.

“In order to do that, you need to have a system that can recognize the expressions of the user,” Martinez says.

Identifying new emotions could also help people who suffer from face blindness – a cognitive disorder that prevents someone from distinguishing between different faces or facial expressions.

When Martinez and his colleagues started their experiment, he didn’t expect for all 21 compound emotions to be true emotion categories.

“I was happily surprised,” he jokes.