Story highlights

As a youth, Mandela was a boxer and long-distance runner

As president of South Africa, he helped bring world attention to his country through sports

"Sport has the power to change the world," Mandela said

Mandela was a major factor in South Africa hosting the 2010 World Cup finals

“Sport has the power to change the world,” Nelson Mandela once said – and the South African prisoner-turned-president also provided perhaps the most eloquent supporting evidence for his claim.

“It has the power to inspire,” he said. “It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair. It is more powerful than government in breaking down racial barriers.”

That last sentence was the closest Mandela came to referencing his own role in using sport to unify South Africa, a country that had been separated by skin color and the warped political ideology of apartheid for nearly half a century by the time he became its first black president in 1994.

A year after winning South Africa’s first multiracial elections, and five years after his release from prison after nearly three decades of incarceration for his anti-apartheid activities, the then-African National Congress leader revealed his acute political antennae as South Africa hosted the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

The sport had long been seen as the white man’s game in South Africa, and many non-whites identified the national team, the Springboks, as being synonymous with minority rule. The team’s antelope emblem had been proudly worn by the country’s whites-only sporting teams during apartheid.

As the onetime pariah state found itself in the unusual position of welcoming the world, there were widespread fears of a racial bloodbath. Some groups were keen to avenge the years of racial oppression, while some right-wing whites were plotting violent protests against the new black majority rule.

Despite their readmission in 1992 to international rugby, after years of apartheid-enforced sporting isolation, South Africa used home advantage so well that the debutants reached the World Cup final.

The sporting, political and human drama was told in John Carlin’s book “Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation” and was made into the movie “Invictus,” with Morgan Freeman playing Mandela.

Carlin tells the story of the moment on the day of the final when white South Africans took a man they once considered a terrorist into their hearts.

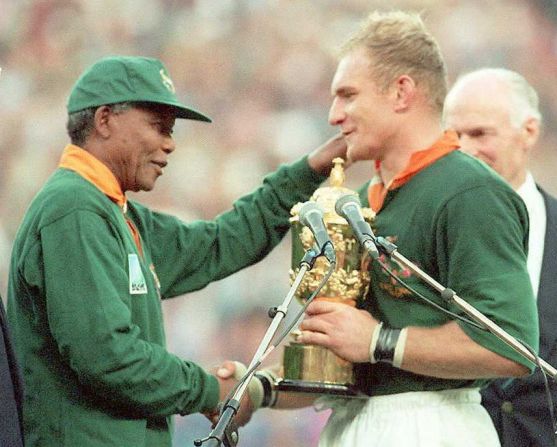

“The day’s crowning moment came before the game had even begun, when Mandela went out onto the field, before a crowd of 65,000 that was 95% white, wearing the green Springbok jersey, the old symbol of oppression, beloved of his apartheid jailers,” he wrote.

“There was a moment of jaw-dropping disbelief, a sharp collective intake of breath, and suddenly the crowd broke into a chant, which grew steadily louder, of ‘Nelson! Nelson! Nelson!’”

Two hours later, the day’s images adopted iconic status as the “Rainbow Nation” beat New Zealand to win the tournament, precipitating widespread celebrations, increased harmony and a mixture of both pride and hope to a South Africa in desperate need of reconciliation.

The photo of team captain Francois Pienaar receiving the trophy from Mandela, who was wearing the No. 6 jersey associated with the Springboks’ Afrikaner skipper, now takes a place of pride at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg.

Nonetheless, Dr. Ashwin Desai, a university lecturer, sociologist and specialist in South Africa’s racial history, believes that the impact of the moment was short-lived and began to crumble within a few months of the final.

“The Rainbow Nation and Mandela’s legacy was supposed to be about the erosion of racial categories, but that has not happened,” said Desai. “This idea that sport can harmonize a nation is a cliché that South Africans use – but we also know that sport can divide. The kindest thing to say about the dream of the Rainbow Nation is that it has been deferred – more realistically though, the dream has been shattered. What we have now is deepening racial division, with racial categories being pre-eminent again.”

Yet one of the most celebrated pages in modern race relations would never have been written had Mandela not saved the Springbok emblem, which was labeled “deeply offensive” by the National Sport Council in the mid-1990s because of its use in the racially divisive past.

Recognizing that whites had lost both their national flag and the elevated status of their national anthem, Mandela understood their need to retain some identity – and so the pacifier persuaded his colleagues that the Springboks’ survival was key to building the new South Africa.

Mandela won the argument despite the Springboks’ history of breaking the international sporting ban that the ANC had successfully forced on many South African teams during apartheid.

Even though he had backed the boycott from his prison cell on Robben Island, Mandela was aware of the sacrifices imposed on his nation’s best sportsmen.

“I wanted my people to know that I became president sooner because of the sacrifices made by our athletes during the years of the boycott,” he replied when asked why he was at a soccer match involving South Africa, rather than a politically themed event, shortly after his inauguration in May 1994.

Two years later, Mandela and South Africa repeated the trick – this time with soccer, the game that was the main preserve of the country’s black community.

With Mandela now draped in the football jersey, South Africa used home soil to win the Africa Cup of Nations, the continent’s premier football event, at the first time of asking.

Yet Mandela’s true football legacy came when South Africa was awarded the honor of staging the 2010 World Cup finals, beating favorites Morocco 14-10 in the final vote.

“The presence of Mandela when we were making our bid was very, very powerful,” said Desai. “We were up against some big, powerful nations, such as Morocco and Egypt, so to beat off Morocco meant there had to be an extra player on the team – and certainly the major game-changer was Mandela.”

“It is thanks to Mandela that the world could finally trust us to deliver this event at a world class level,” Danny Jordaan told the FIFA website. “He gave us a momentum and self-belief that we could achieve what many thought was impossible and we, and this country, will be forever grateful.”

Despite a personal tragedy on the eve of the finals – his great-granddaughter Zenani, 13, died in a car crash – Mandela was ultimately rewarded with a tournament that shone with color, originality and, to widespread surprise outside South Africa, fine organization.

Within Africa, many said they felt an increased sense of belonging as the football World Cup, which dates back to 1930, finally arrived in Africa – the first time the continent had hosted a global event on the scale of the Olympics.

FIFA President Sepp Blatter hailed Mandela as an “extraordinary person” on Thursday and recalled the ecstatic scenes at the 2010 World Cup’s closing ceremony in what proved to be Mandela’s final public appearance.

“When he was honored and cheered by the crowd at Johannesburg’s Soccer City stadium on 11 July 2010, it was as a man of the people, a man of their hearts, and it was one of the most moving moments I have ever experienced. For him, the World Cup in South Africa truly was ‘a dream come true,’” Blatter said in a statement on FIFA’s website.

“Nelson Mandela will stay in our hearts forever. The memories of his remarkable fight against oppression, his incredible charisma and his positive values will live on in us and with us.”

Former South African international, Lucas Radebe also paid a moving tribute.

“The sports history books in South Africa will show statistics and victories. What they won’t show, however, was that it was Madiba Magic that forged those results and performances; and united a country and its people along the way. No doubt, that Madiba Magic will live on. Thank you Tata,” Radebe wrote on his website.

This sense of belonging is one that Mandela maintained with his foundation, the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, which started the Sport for Good program with the aim of using sport as a way of improving the lives of children in both South Africa and Swaziland.

This sporting philosophy had served Mandela himself exceptionally well during his time in prison. In his biography, “A Long Walk to Freedom,” he explained how he followed a highly disciplined exercise regime in a bid to stay both physically and mentally healthy.

“I have always believed that exercise is a key not only to physical health, but to peace of mind,” wrote the once-keen boxer and long-distance runner. “Exercise dissipates tension, and tension is the enemy of serenity.”

“In prison, having an outlet for my frustrations was absolutely essential. Even on the island, I attempted to follow my old boxing routine of doing roadwork and muscle-building from Monday to Thursday and then resting for the next three days.”

The efficacy of his discipline – which also included 45 minutes of running “on the spot in my cell” and extensive anaerobic exercise four times a week – was clear to see in the energy he brought to life as a free man – keeping together the fragile, new South Africa, visiting world leaders and becoming one of the political icons of our time.

After 27 years behind bars, where he was allowed just one visitor a year, perhaps it was only fair that the world then came to visit Mandela in later years – with Pele, Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Alex Ferguson, Tiger Woods and David Beckham prominent among the sporting luminaries to meet the icon.

Like the wider world, sport is unlikely to forget Mandela, not just because of the tournaments and stadiums already named in his honor, but primarily for a day in 1995 when the anti-apartheid activist stole the show during the defeat of a team called, ironically enough, the All Blacks.

Read more: Nelson Mandela’s legacy: How soccer club fell for Africa

Read more: D’Oliveira: The man who took on the apartheid regime

Read more: Pienaar recalls day Mandela transformed South Africa