Story highlights

Some of our greatest presidents were skillful liars

Machiavelli said a leader must be a "great pretender"

The difference between good vs. bad lies

Why one honest president should have learned how to lie

“I cannot tell a lie.”

That’s the signature line from a classic American story. When the nation’s first president was asked as a boy if he had chopped down his father’s cherry tree, he didn’t say “I can neither confirm nor deny those reports,” or “it depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

George Washington told the truth even if it got him in trouble. The moral of the story – Washington was a great leader because he would not lie, and all presidents should be as honest as our founding father.

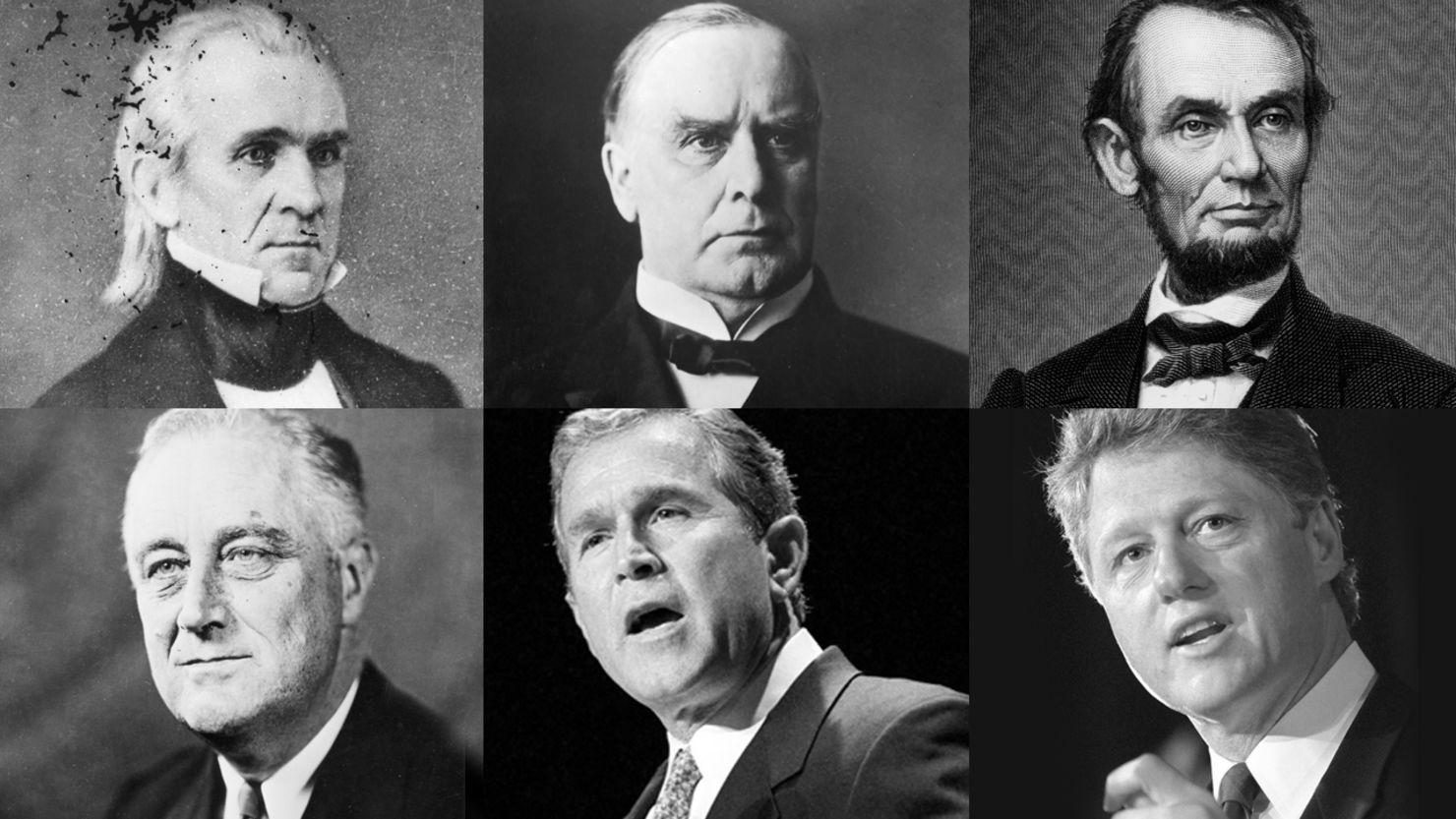

Well, guess what? That story about Washington and the cherry tree is a lie. Never happened. And the notion that a good president doesn’t lie to the American people – that’s an illusion as well. Historians say many of our greatest presidents were the biggest liars – and duplicity was part of their greatness.

“Every president has not only lied at some time, but needs to lie to be effective,” says Ed Uravic, a former Washington lobbyist, congressional chief of staff and author of “Lying Cheating Scum.”

Presidential lying is a hot topic because of a promise made by President Obama. While promoting Obamacare, Obama told Americans that they could keep their health insurance if they wanted to. That turned out to not be true for some, and Obama has been accused of lying.

Some political pundits warn that Obama’s “lie” will undo his second term. They say Americans won’t forgive a president who violates their trust. It’s a good sound-bite, but it’s bad history. A great leader must “be a great pretender and dissembler,” Machiavelli said in “The Prince.” And so should a president, some historians say.

You might say lying is the verbal lubricant that keeps the Oval Office engine running. Some of our most popular presidents told the biggest whoppers, say historians, including Benjamin Ginsberg, author of “The American Lie: Government by the People and other Political Fables.”

While preparing the country for World War II, Franklin Roosevelt told Americans in 1940 that “your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”

President John F. Kennedy declared in 1961 that “I have previously stated, and I repeat now, that the United States plans no military intervention in Cuba.” All the while, he was planning an invasion of Cuba.

Ronald Reagan told Americans in 1986, “We did not, I repeat, did not trade weapons or anything else [to Iran] for hostages, nor will we,” four months before admitting that the U.S. had actually done what he had denied.

Even “Honest Abe,” whose majestic “Gettysburg Address” the nation commemorated this week, was a skillful liar, says Meg Mott, a professor of political theory at Marlboro College in Vermont.

Lincoln lied about whether he was negotiating with the South to end the war. That deception was given extended treatment in “Steven Spielberg” recent film “Lincoln.” He also lied about where he stood on slavery. He told the American public and political allies that he didn’t believe in political equality for slaves because he didn’t want to get too far ahead of public opinion, Mott says.

“He had to be devious with the electorate,” Mott says. “He played slave-holders against abolitionists. He had to lie to get people to follow him. Lincoln is a great Machiavellian.”

6 things presidents wish they hadn’t said

Forgivable vs. unforgivable lies

Presidential lies fall into two categories: forgivable vs. unforgiveable.

Forgivable lies are those meant to keep the nation from harm. Some consider the National Security Agency’s lies about the scope of domestic spying to be in this category because they protect us from terrorists, says Uravic, author of “Lying, Cheating Scum.”

Unforgivable lies fall into the Nixonian “I am not a crook” category, Uravic says.

Those are lies meant to cover up crimes, incompetence or protect a president’s political future. President Lyndon Johnson, for example, kept the full cost of spending on the Vietnam War from Congress and the public to preserve his political power, Uravic says.

“The American people remain forgiving of their politicians, as long as those politicians put the people first and deliver tangible benefits for all of us,” says Uravic, who also teaches at the Harrisburg University of Science and Technology in Pennsylvania.

The ultimate test of whether the American public will accept a lie from a president is if the nation determines that the lie serves the national interests.

That distinction is why Bill Clinton remains popular, and George W. Bush remains reviled for his “lie,” says Allan Cooper, a political scientist and historian at Otterbein University in Ohio.

In a nationally televised address in 2003, Bush said that invading Iraq was necessary “to eliminate weapons of mass destruction.”

“Intelligence gathered by this and other governments leaves no doubt that the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised,” Bush said.

Clinton told the nation that he did “not have sexual relations with that woman.”

“Clinton’s lies about a sexual affair were understandable given his interest to protect his marriage and to shield the nation’s children from having to ask their parents to explain the phenomenon of oral sex,” Cooper says. “Bush’s lies led to the death and injuries of thousands of Americans.”

Obama’s statement will be judged by the same standard: Did it help the country, or did he say it just to save his bacon?

Obama apologized for saying people could keep their insurance if they like it. But some Americans who buy policies on the private market recently received cancellation notices because their plans don’t meet Obamacare requirements for more comprehensive care.

Americans may forgive Obama if Obamacare improves their lives, says Christopher J. Galdieri, who teaches a course on the U.S. presidency at Saint Anslem College in New Hampshire.

“Ultimately, this is going to come down to whether the federal [health care] exchange improves, and whether people come to view that as a successful and viable option for buying insurance for themselves and their families,” Galdieri says.

Will George W. Bush’s reputation ever recover from the accusation that he led the nation into war under false pretenses? It’s hard to say from history.

Several presidents were accused of deceiving the American public to sell military action, says David Contosta, a history professor at Chestnut Hill College in Pennsylvania.

President James Polk lied to Congress in 1846 – claiming Mexico had invaded the United States – because he was determined to take the Southwest from Mexico. That lie led to the Mexican-American War, Contosta says.

President William McKinley lied to the American public in 1898 when he insisted that Spain had blown up the USS Maine warship in Havana Harbor, Cuba, although he had no evidence. That lie led to the Spanish-American war.

One popular president got caught telling a lie about a failed military action but his popularity remains intact.

“President Dwight Eisenhower denied that the United States was flying U-2 spy planes over the Soviet Union, until the Soviets shot down one of the planes, capturing the pilot, and he was forced to admit the truth,” Contosta says.

Some presidents were so deceitful that they even lied to their friends.

Franklin Roosevelt was such a president. Roosevelt led the nation out of the Great Depression and through World War II. But even his allies couldn’t bank on honesty.

Roosevelt told three different men that he wanted them to be his next vice president during the Democratic national convention in 1944. Then he picked a fourth man, Harry Truman, for the office, says David Barrett, a political science professor at Villanova University in Pennsylvania.

“He did it with such skill that all three men were completely convinced that Roosevelt was behind him.”

The lost art of the quotable speech

Why we need a president who lies

Roosevelt’s deceitfulness hasn’t stopped historians from widely picking him as one of nation’s three greatest presidents, along with Lincoln and Washington. Perhaps they and ordinary Americans forgive presidents who lie because there’s something in human nature that believes a leader needs to be cunning.

Sure, we tell our children about Washington cutting down the cherry tree. The 19th century writer Parson Mason Weems inserted that fable into his 1800 biography “A Life of Washington.”

But then we close the children’s book and turn on the TV to admire the lethal duplicity of a leader like the mafia patriarch Vito Corleone in the classic 1972 film “The Godfather.”

We want our presidents to have a little gangster in them. It’s the presidential paradox that scholars Thomas Cronin and Michael Genovese talked about in their recent book, “The Paradoxes of the American Presidency.”

They wrote:

“We want a decent, just, caring, and compassionate president, yet we admire a cunning, guileful and, on occasions that warrant it, even a ruthless, manipulative president.”

The most sublime execution of presidential deception comes when a president discovers that he doesn’t have to lie to deceive. Why lie when a simple misimpression will do, says James Hoopes, an ethics in business professor at Babson College in Massachusetts.

These presidents learn from Machiavelli, who said that the Prince must be a “fox and lion” – a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify enemies who would trap him, Hoopes says.

President Andrew Jackson foxily campaigned on a lie insisting that he was for a “judicious tariff” which to Southern ears in the 1828 presidential election meant a low tariff. After Jackson was elected, though, Congress passed a high tariff that prompted outraged Southern leaders to talk about nullification and secession, Hoopes says.

The fox then became the lion, Hoopes says of Jackson.

“Like the lion he was, Jackson faced down the challenge with threats of force, threats that had the ring of truth, coming from a former general who summarily executed enemy civilians and hanged mutinous soldiers under his command,” Hoopes says.

If you still think you want a leader who is always honest, consider the fate of one recent president.

He vowed during his presidential campaign that “I will never tell a lie to the American people.” He wore a sweater during a nationally televised speech from the Oval Office because he had turned down the White House thermostat to conserve energy. He brought peace to the Middle East and even taught Sunday school.

He was also swept out of the Oval Office after one term.

“The country fell apart,” Mott says of this president’s time in office. “He was too noble, too pure. He didn’t know how to play people against one another. He should have read his Machiavelli.”

That president was Jimmy Carter. He won the Nobel Peace Prize after leaving office, and he’s been widely praised for his humanitarian efforts around the globe. He still builds homes for the poor around the world.

No one ever labeled Carter a liar while he was in office.

But then hardly anyone calls him a great president today.