Editor’s Note: Laurie Garrett is senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist.

Story highlights

Syria's Assad regime is accused of using chemical weapons on civilians

Laurie Garrett: Sarin probably was deployed; those who die from it suffer terribly

She says sarin was developed in WWII era as a potent form of destruction

Garrett: It would be nightmare for Syrians to experience toxic gas in a litany of despair

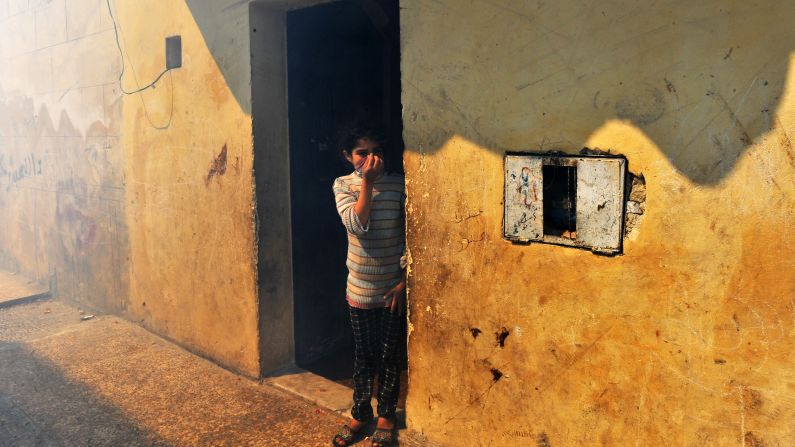

This week, the world is learning that on August 21, Syria’s Assad regime attacked civilians living on the outskirts of Damascus, killing at least 355 of them, including many small children. According to Vice President Joe Biden, there is “no doubt” that chemical weapons were used by the regime – and not, as the Assad government has claimed, by rebel forces.

The victims suffered terrible and painful deaths. Many experts are concluding that most likely a nerve agent such as sarin was deployed. Sarin is a type of organophosphate (OP), a class of chemicals used for making herbicides, insecticides and nerve gases.

The effects of sarin and other OPs on the human body are profound, shocking and can be long lasting. Some exposures have left the surviving victims paralyzed for weeks, with perhaps permanent liver malfunctions and lingering neurological dysfunctions.

OPs disintegrate in a matter of hours. But during their comparatively brief period of volatile danger, the deadly molecules can pass through human skin, nostrils, lungs and eyes to enter the bloodstream and then the brain. If enough of it gets inside the brain to saturate the nervous system, an agonizing death follows.

I first learned about sarin gas in 1978 when I was hired by the California Department of Food and Agriculture to assess the human health impacts of 33,000 pesticide formulations used by farmers and pest eradication companies. Obviously the state wasn’t serious about this. Who hires a 26-year-old graduate student immunologist to, by herself, evaluate so many chemicals?

What I found was that among the tens of thousands of chemicals used by growers and pest eradicators around the world, the most potent and popular were, and still are, the organophosphates. They kill insects by blocking proper regulation of the key chemical used by nerve cells, acetylcholine. (OPs became popular for agricultural use after DDT and some other chemicals were banned because they persist almost indefinitely in the environment.)

But now and then, a farmworker might inhale the odorless, tasteless OP chemicals when unknowingly downwind of a large pesticide spraying, and the ghastly neurological symptoms and deaths would ensue.

To understand how and why such dangerous compounds had come into common use, I dug backwards in the scientific literature, landing on the 1938 invention of the first member of this chemical family, sarin, developed by German chemist Gerhard Schrader.

Though Schrader started down the sarin path in search of agricultural chemicals, he recognized its utility as a nerve gas and aided his military in its development and use during WWII. During the Cold War, the United States, United Kingdom and Soviet Union all developed deadlier forms of OPs, including VX gas.

In 1993, the U.N.’s Chemical Weapons Convention banned sarin, VX and other nerve gases. The CWC also targeted compounds used to make deadly gases, such as methylphosphonyl difluoride – a harmless chemical until mixed with rubbing alcohol, creating sarin. The CWC was signed by 162 nations, including the U.S. and Soviet Union. But Syria has never signed it, and the regime of Bashar al-Assad has stockpiled ready-to-mix methylphosphonyl difluoride in vast quantities.

Three decades ago, I found it shocking to learn that so much OP pesticides used annually in the United States to control insects were, chemically, close siblings to those deployed for genocidal purposes.

But then it came back as a weapon of war.

On March 16, 1988, the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein showered the Kurdish village of Halabja with multiple chemical agents, including sarin, killing several thousand civilians. This was the largest-scale chemical weapons attack in modern history.

Seven years later, the first terrorist use of sarin occurred in Tokyo, carried out by the strange religious cult Aum Shinrikyo. On March 20, 1995, the group released sarin in the city’s subway system, killing 13 people and injuring more than 6000, with many requiring hospitalization.

More recently, an apparently corrupt principal in India fed children in her school cheap, OP-contaminated lunches, killing at least 25 youngsters. Witnesses described the children’s hideous deaths as the pesticides caused their nervous systems to send signals to their muscles, leading to spasms and seizures. And then, in response, their lungs became paralyzed and the terrified children gasped and suffocated until they died.

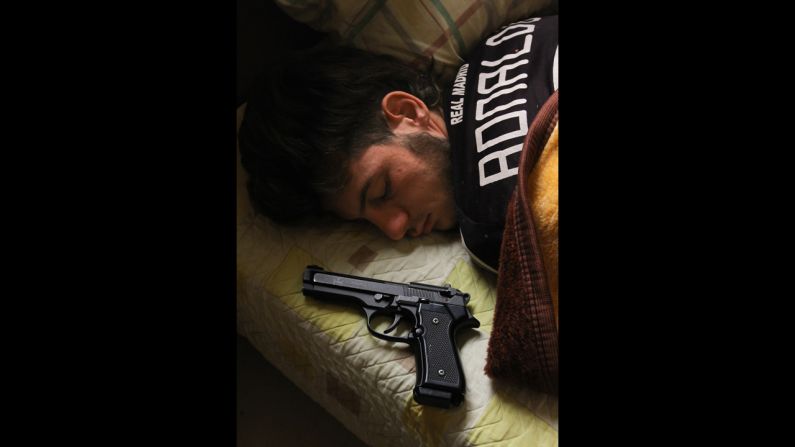

In December, The New York Times and WIRED magazine reported that the Assad government was moving some of its chemical weapons in an apparent preparation for an attack. The deadly stockpile was stored in a safe form. A launchable shell is divided in half by a thin membrane.

On one side is rubbing alcohol, on the other, methylphosphonyl difluoride. Divided, the chemicals pose no hazard and can easily be transported and stored. But upon detonation, the membrane bursts, the chemicals mix, sarin gas is made and it showers upon those unfortunates below.

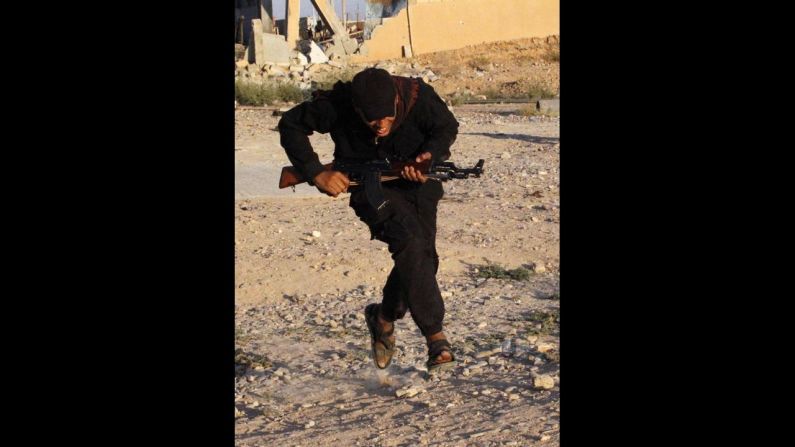

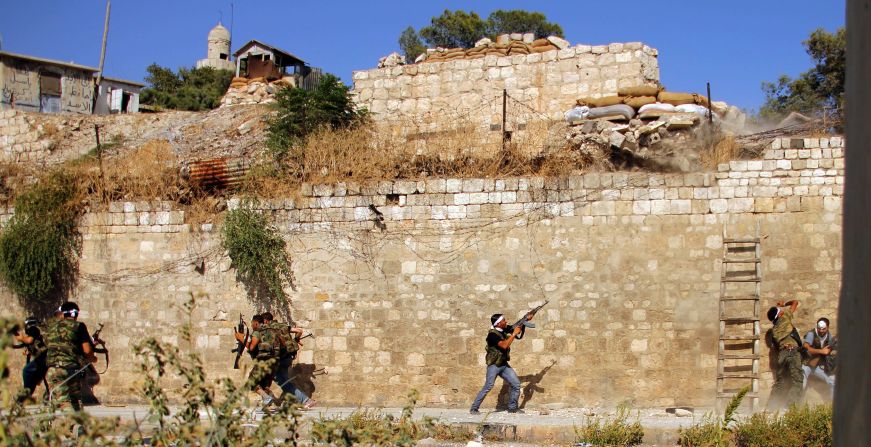

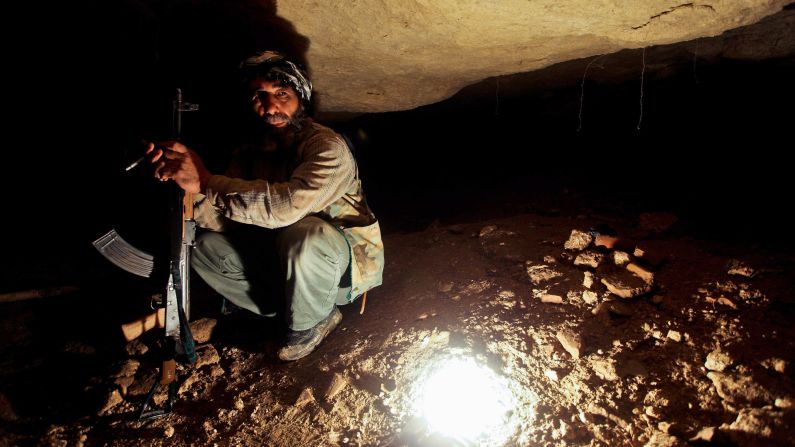

In March, sarin was used in Syria in a small attack. U.N. investigators have testimony that rebel forces may have used it. This month’s attacks outside of Damascus, however, was clearly carried out by the Assad regime, according to the U.S and Britain.

A year ago on August 20, President Barack Obama made his now-famous “red line” remark, stating: “We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized. That would change my calculus. That would change my equation.”

That was the diplomatic line in the sand for the U.S. In October of the same year, Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s foreign minister at the time, addressed the Council on Foreign Relations in New York and drew his line. I asked him, “If the Syrian government makes use of its well-known stockpiles of either biological or chemical weapons, and the wind blows said weapons across your border, claiming Iranian lives, will this be considered a national security threat?”

“Certainly, that situation is a situation that will end everything,” Salehi said. Iran is the key ally of the Assad regime. But what if powerful winds were to carry sarin or other chemical weapons from Syria to the Iranian border?

Salehi added, “that is the end of the validity, eligibility, legality, whatever you name it, of that government. Weapons of mass destruction, as we said, is against humanity. It’s something that is not at all acceptable. And therefore, if your hypothesis, God forbid, ever materializes, I think nobody can justify it anymore, nobody can go along with anybody who has been involved in such act of – I would say inhuman act.”

The Assad regime is playing with regional fire.

While the possibility of a wind carrying sarin to far-away Iran might be ridiculous, the Lebanese border is merely 15 miles from Damascus and Jordan’s is 70 miles away.

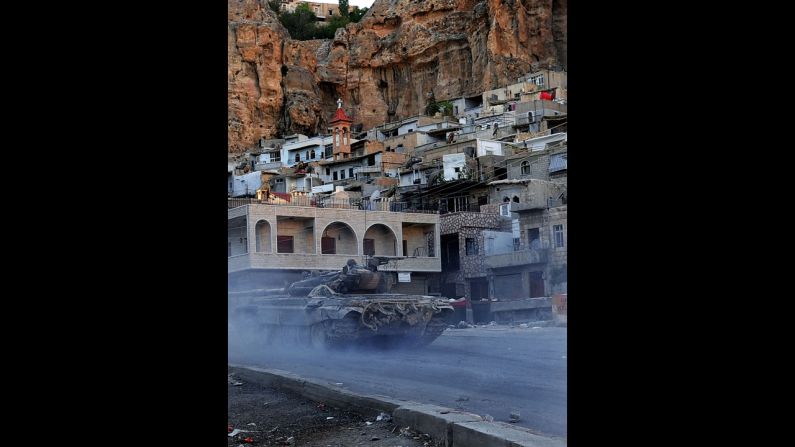

A “new normal” has descended over the Middle East since the 2011 Arab Spring, pushing ever more dangerous boundaries of instability and brutality, mass refugee exoduses, tough military crackdowns, suicide bombings, demolition of mosques and Coptic churches and spread of diseases.

It would be nightmarish in the extreme were use of chemical weapons – deployment for purposes of mass asphyxiation – to join the awful “new normal” litany of despair.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Laurie Garrett.