Story highlights

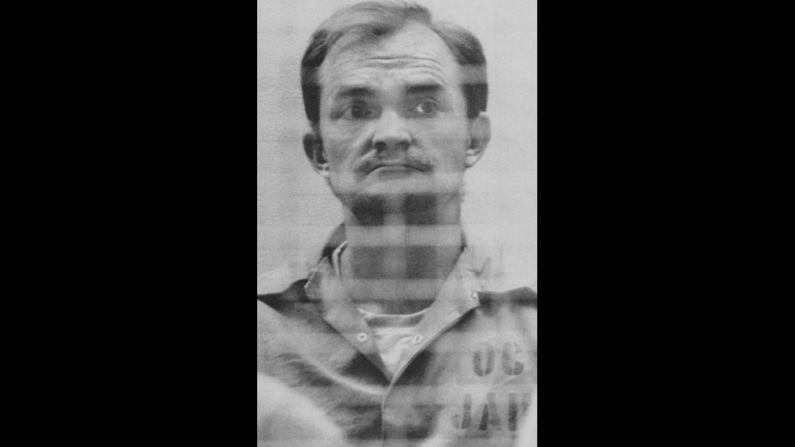

Officials: Anthony DeSalvo's DNA matches evidence from a Boston Strangler killing

The victim was 19 when she was raped and murdered in her apartment in 1964

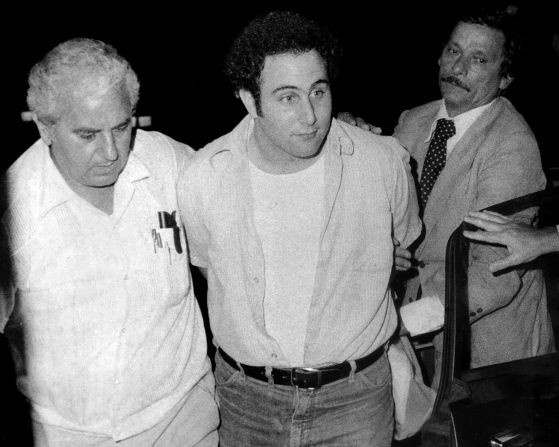

DeSalvo had confessed, then recanted; he died in 1973

His body was exhumed this month so a DNA sample could be extracted

New light has been shed on one of the most famous serial killer cases in history.

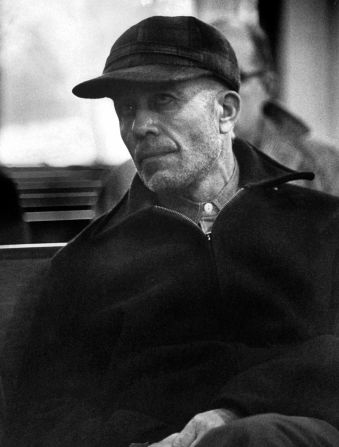

A lab test confirms DNA evidence taken from the body of a murder victim matches Albert DeSalvo, who at one point confessed to being the Boston Strangler, Massachusetts authorities said Friday.

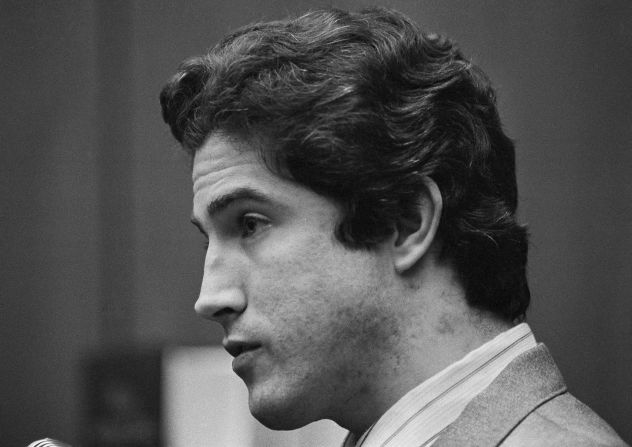

The evidence was taken after Mary Sullivan, 19, was sexually assaulted and strangled to death on January 4, 1964, in her Charles Street apartment in Boston.

DeSalvo had confessed to that crime and about a dozen other murders police attributed to the Boston Strangler. However, he recanted his admissions and was never convicted of any of them before his death.

Although many continued to believe DeSalvo was the Boston Strangler despite his retraction, others expressed doubts.

Now, however, there is an “unprecedented level of certainty” that DeSalvo raped and killed Sullivan, Suffolk County District Attorney Dan Conley said in a news release Friday.

Officials announced the results after notifying Sullivan’s family of the findings, the release said.

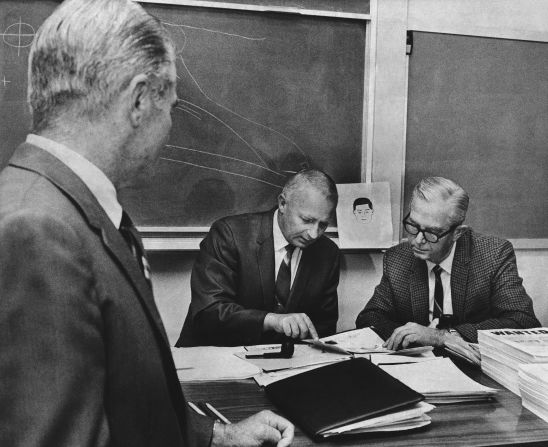

See more: City of fear, photos from the Boston Strangler era

“Questions that Mary’s family asked for almost 50 years have finally been answered. They, and the families of all homicide victims, should know that we will never stop working to find justice, accountability, and closure on their behalf,” Conley said.

Boston Police Commissioner Edward Davis credited “a relentless cold case squad” who “refused to give up, waiting until science met good police work to solve this case.”

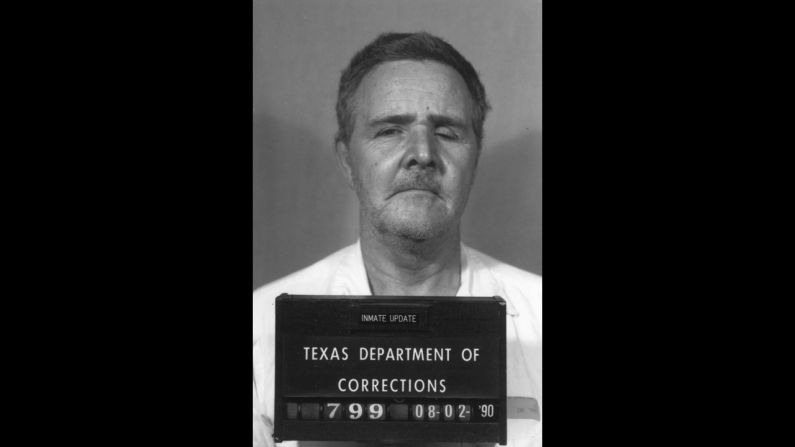

DeSalvo was stabbed to death in 1973 while serving a life prison term for unrelated rapes.

Solving a murder with DNA

Conley said earlier this month that scientists had tried several times in the late 1990s and early 2000s to isolate DNA evidence from semen found in Sullivan’s body and on a blanket. They resumed their efforts last year, after scientific advances had led to a laboratory successfully salvaging DNA from decades-old material.

Boston Police Crime Laboratory technicians were able to extract DNA profiles from both sets of samples, and those DNA profiles matched one another, the news release says.

The DNA profile was uploaded to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System. Known as CODIS, it stores the DNA profiles of millions of known offenders, the release says. But there was no match. That ruled out at least one man who earlier been an unofficial suspect in Sullivan’s slaying, it says.

Investigators then went on a search for any other evidence that might contain DeSalvo’s DNA. But each place that might have had suitable samples – like the Department of Correction, the Massachusetts State Police and others – did not.

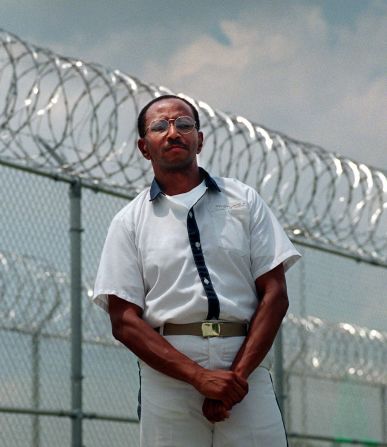

Knowing Y chromosomes are passed down “almost unchanged” from father to son, Boston Police retrieved a water bottle that one of DeSalvo’s nephews drank from and threw away. Police revealed this action earlier in July.

Although the DNA recovered from the bottle was a “familial match” with the genetic material preserved from Sullivan’s murder, Conley said at that time that it wasn’t enough to close the case with certainty.

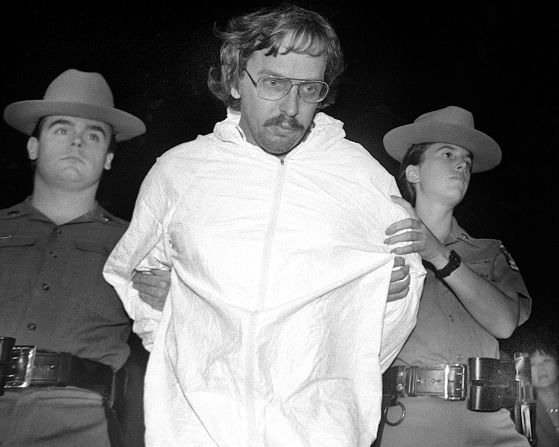

It did, however, lead to a judge approving DeSalvo’s exhumation so a DNA sample could be taken directly from him.

On July 12, DeSalvo’s grave was excavated and his remains were transported to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Comparisons were made, officials said, and the match was confirmed.