Story highlights

DR Congo moving ahead with plans to build the world's biggest hydroelectric project

When complete, Grand Inga could have a massive capacity of 40,000 megawatts

Project construction will begin in October 2015

But critics argue that the project will only serve the mining firms and not benefit the rural poor

The world will have seen nothing like it.

It is being hailed as the holy grail for power, the biggest hydroelectric project ever built that would harness sub-Saharan Africa’s greatest river and light up half of the continent.

But will the ambitious plan to tame the mighty Congo River, a mega-project first conceived in the 1970s, finally get going and what will be its actual impact?

Last month, the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo announced in Paris that the construction of the first phase of a new set of energy projects at the country’s Inga Falls would begin in October 2015. The new $12 billion development, dubbed Inga 3, is expected to have a power output of nearly 4,800 megawatts (MW), with South Africa agreeing to buy half of the electricity generated.

But the DRC government’s bold vision ultimately involves five further stages that would complete the “Grand Inga” mega-project, giving it an astonishing capacity of 40,000 MW – that’s twice as much as the Three Gorges dam in China, currently the world’s largest hydro project.

When completed, Grand Inga could provide more than 500 million people with renewable energy, say its proponents.

“A myth dreamed of for 40 years, Grand Inga is becoming a reality with an action plan spread over several plants which will be added in stages,” the DRC government said in a statement after the Paris meeting.

Powerful river

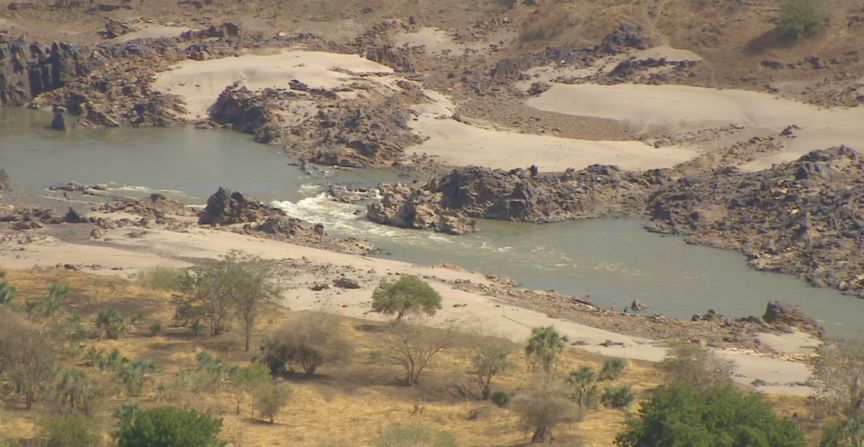

With a length of 4,700 kilometers, the Congo is Africa’s second biggest river, after the Nile, and the world’s second largest river in terms of flow, after the Amazon. At the Grand Inga site, some 1.5 million cubic feet of water flow steadily through a network of cataracts every second, dropping about 100 meters to form the world’s biggest waterfall by volume.

Yet the power potential from the river’s rapids has largely gone unexploited in a country plagued by violence and corruption for decades – just 11.1% of the DRC’s population has access to electricity, according to the World Bank.

Read this: Africa’s new skyscraper cities

So far, the only two projects built to tap Congo’s potential are two smaller dams – Inga 1, commissioned in 1972, and Inga 2, a decade later. Both of them are almost exclusively used to provide energy for the mining companies in the southern DRC’s copper belt but are currently undergoing extensive rehabilitation as they perform far below capacity.

Seeking funds

The DRC government hasn’t yet decided on the developer of Inga 3, but three consortia from China, Spain and Korea/Canada are the frontrunners in the competitive selection process. The financing will come from both public and private sources: the Africa Development Bank, the World Bank, the French Development Agency, the European Investment Bank and the Development Bank of Southern Africa have all been named as potential contributors.

But will the DRC, a country with a risky investor profile, be able to raise enough money to build the mammoth project? Some say that with $12 billion required just for Inga 3 – the entire project has an estimated cost of $80 billion – it’s going to be an extremely tough and complex task to find the huge sums needed.

“It almost defies imagination that this kind of money is going to be available,” says James Leigland, technical adviser to the Private Infrastructure Development Group. He notes that several different players will “have to come to the party with equity,” from multilaterals, commercial and national development banks to the DRC government and the developer of the project.

“It is hard to imagine how all of this is going to fall into place,” says Leigland. “They’ve started, they’ve made a commitment to proceed on the basis that South Africa will take a huge amount of the power, but getting from here to there it’s just a very long road,” he adds.

Transferring power

Indeed, the pledge by energy-hungry South Africa to purchase about half of Inga 3’s future power production is essential for the project to attract finance and get going.

The two countries are currently negotiating a treaty to finalize the details of a power purchasing agreement, including the construction of transmission lines to transfer 2,500 MW of Inga 3’s production to South Africa. The exact routing of the energy corridor is not yet defined, but it is expected to be over land, through different countries in the southern part of the continent.

Read this: ‘Wind of change blowing through Africa’

A World Bank spokesperson told CNN that such power exports could potentially raise considerable revenues for the DRC. “With energy resources on this scale, DRC can play a pivotal role in meeting not only its future domestic energy needs for poverty reduction and economic development, but also the energy needs at regional and continental levels,” said the spokesperson.

“With only one in 10 Congolese households having access to electricity, development of projects like Inga 3 and subsequent Grand Inga is essential for growth, more jobs and improved well-being in Africa.”

Power to the people?

Yet, not everyone agrees. With half of Inga 3’s power traveling south, and nearly all of Inga 1 and 2’s energy bypassing the DRC’s rural communities to be consumed by the mining industry, critics say the country’s poor will see no benefits from the project.

“All the electricity that will be generated from Inga 3 is for commercial purposes and nothing is going to supply the communities,” says Rudo Sanyanga of International Rivers, an NGO working against destructive riverside projects.

“The assumption being promoted is that by developing Grand Inga and exporting, or supplying the mines, will then create jobs in the mining industry and it will trickle down to the community – but it has never worked,” adds Sanyanga.

Read this: ‘Solar sisters’ spreading light in Africa

Instead of pouring billions into mega-schemes, the group argues there are less costly and more effective solutions that can be deployed to tackle the continent’s energy poverty, especially wind, solar and micro hydropower projects.

“They should prioritize decentralized energy and have a combination of grid and off-grid planning,” says Sanyanga. “If they really want to get electricity to the people, not only in the rural areas but as well as in the cities, they have to have another plan which is cheaper than grid development.”