Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of our series “Life’s Work,” which will feature innovators and pioneers making a difference in the world of medicine.

Story highlights

Dr. Vincent Gott is associated with the first open-heart surgery

He helped develop the pacemaker and now uses one himself

He says he never envisioned that the pacemaker would become so widespread

Dr. Vincent L. Gott was part of an innovative group of doctors who trained with Dr. C. Walton Lillehei, considered to be the father of open-heart surgery.

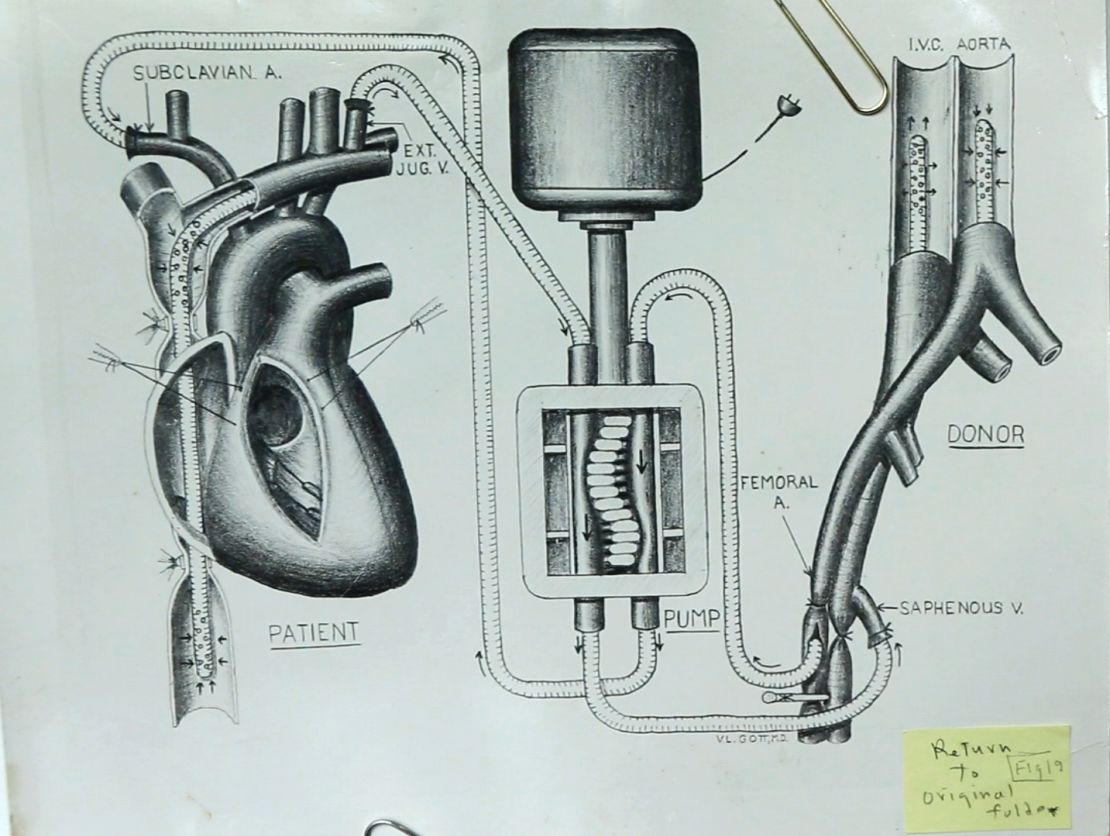

When Lillehei performed the first open-heart surgery in 1954, Gott was observing as an intern. He later drew an illustration of the operation showing the defects in the patient’s heart, which caught Lillehei’s eye. Gott went on to become one of the pioneers in the development of the pacemaker – a device that he himself benefits from today.

Gott stopped operating at 67, but kept working until age 81, seeing patients, teaching medical students and doing research. These days, Gott, 86, is retired and writing a children’s book about the history of cardiac surgery.

Gott met with CNN to talk about his influential career.

Did you originally want to become an artist?

(chuckles) When I was 12, my folks enrolled me in an art class, and I enjoyed it very much. And I continued with my art. Really, when I got to Baltimore in 1965, I took art lessons once a week from a very fine illustrator-artist, Ann Schuler.

So it was helpful and in fact, as you know, I made a sketch of that very first operation of Dr. Lillehei’s little boy’s heart and all, and it was really that sketch that caught Dr. Lillehei’s attention, and got me into his lab and into heart surgery.

I’ve really enjoyed, over the last year and a half, working on a book on the history of heart surgery for young readers. And so I’m just about through with the illustrations. I’m illustrating about 30 different operations and illustrating also about 25 of the most prominent heart surgeons in the world.

Why did you want to become a surgeon?

I had the opportunity of knowing some surgeons in my hometown of Wichita (Kansas), particularly a very prominent plastic surgeon in Wichita and even when I was in high school, I was able to go over and observe his operations. And when I was in medical school, I was able to observe his operations.

I was very influenced at Yale Medical School, when I was a student, by some of the faculty there, the surgeons at Yale. Then when I finished Yale, I thought, well there was no specialty of heart surgery in 1953 when I finished medical school so I decided, well, I want to be a plastic surgeon.

That’s why then I enrolled in a program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis because they had a straight surgical internship, and it was my plan to stay in plastic surgery. And that all changed with Dr. Lillehei’s operation.

You’ve participated in some highly experimental procedures. Do you think it would be harder to do those kinds of procedures today in the current regulatory environment?

That’s a good question. I don’t think so. There’s a regulatory environment, but with cardiac surgery with anything, there’s continual improvement. I’ve seen over my career, tremendous changes and improvements, say, in the management of coronary artery disease.

These procedures we did were not necessarily experimental but they were new, some of the procedures, particularly for the Marfan aneurysm, were new. And I don’t think, sure, we have greater regulation but I think the opportunity for developing new operations has not been stymied or diminished by the new regulations. New regulations, the HIPPA regulations, are really to permit the privacy for the patient in their medical care.

What do you remember about your first heart transplant? Did you think it would work?

Well, first of all, I’d had the opportunity to train with Dr. Christiaan Barnard (a South African surgeon who performed the world’s first heart transplant). Chris Barnard was trained by Dr. Lillehei, so I knew him well. And also the other person who really was active was Dr. Norman Shumway, who was trained by Dr. Lillehei. Dr. Shumway really worked out the technique of heart transplantation (but) wasn’t able to perform it as soon as Dr. Barnard because of our restrictions here in this country on brain death.

We did our first heart transplant, it was in ’67, and was fortunate to have Dr. Harvey Bender, who was on our junior faculty, as he and I performed the operation together. And I remember, we had the donor in one room and the recipient in the adjacent room. In those days, of course, we had restrictions as far as taking the heart from the donor, there had to be brain death before you could take the heart, and that was important.

It was an important day and the operation went well. The patient, as I remember, only lived for about a year. We just didn’t have the great medications or drugs that we have now to prevent rejection. I’ll never forget that day.

LIFE'S WORK AT A GLANCE

How did you get involved in developing the pacemaker?

When Dr. Lillehei was putting these patches in the children to close the ventricaluar septal defect, there’s a critical nerve that runs right along that hole, and it’s invisible. And in about 10% of the patients, the stitch could go around that nerve and then cause the heart rate to go from, say, 100 in a 2-year-old child, to 20, which is not compatible with life.

That was a problem, actually, for almost two years after Dr. Lillehei started his surgery. It was in the fall of 1956 that a young physiologist, Dr. Jack Johnson at the University of Minnesota, said you know, to Dr. Lillehei and the rest of them, ‘I’ve been pacing frog hearts for five years with an electrical stimulator. Why don’t you use that?’

I went over and borrowed this electrical stimulator from Jack Johnson, and we were able to create heart block in a research animal very easily. It’s just a matter of putting a wire in the heart and a wire in the skin, and connecting it up to Dr. Johnson’s electrical stimulator, and it worked. And then Dr. Lillehei started using that in January of 1967, and that was really the start of the pacemaker.

At that time, there was not a portable pacemaker. And these children could not go home with a pacemaker, but Mr. Earl Bakken, who was the president of a small company called Medtronic in Minneapolis, then built a portable, battery powered pacemaker that these children could use.

We never envisioned at that time that there would be literally hundreds of thousands of adults who could benefit from the pacemaker. I in fact received a pacemaker myself five years ago for heart block.

What is the next step in the field of heart surgery?

I think currently the artificial valves that are used are really quite beautifully designed and functioning extremely well, and work for decades. One of the areas that we’re hoping for improvement will be in longevity for patients after a heart transplant. They’re still a problem, and I’ve been out of surgery now for five years so I’m not totally updated on this, but there’s still a problem with rejection of the heart after transplant.

The other major progress as I see as a development is a total artificial heart. Over the last 30 years, there (has) been a lot of research going on in the artificial heart, and we now seem to have an artificial heart that’s certainly fine as a bridge to a transplant. We still, I think, are looking for a better artificial heart that can be implanted and then left as the final heart.

You can see Dr. Gott and other fascinating stories from the world of health and medicine on “Sanjay Gupta MD,” Saturday at 4:30 p.m. ET and Sunday at 7:30 a.m. ET.