Editor’s Note: Follow CNN’s space blog, @CNNLightYears, on Twitter

Story highlights

New images from a space telescope allow scientists to map how the universe evolved

Planck space telescope shows with better-than-ever precision first light of universe

The light is technically from 380,000 years after the Big Bang

New data suggest universe is 100 million years older than scientists thought

How cute was our universe as a baby? We now know better than ever: The picture of our early universe just got sharper and tells scientists with greater precision many important facts about how the universe evolved.

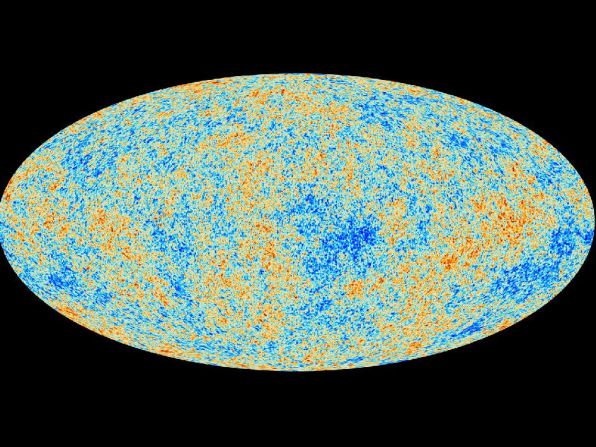

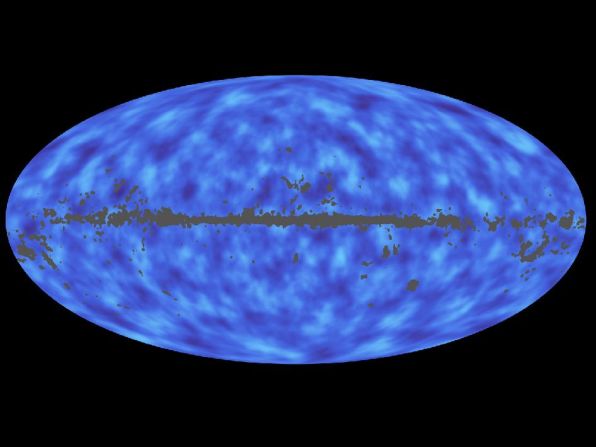

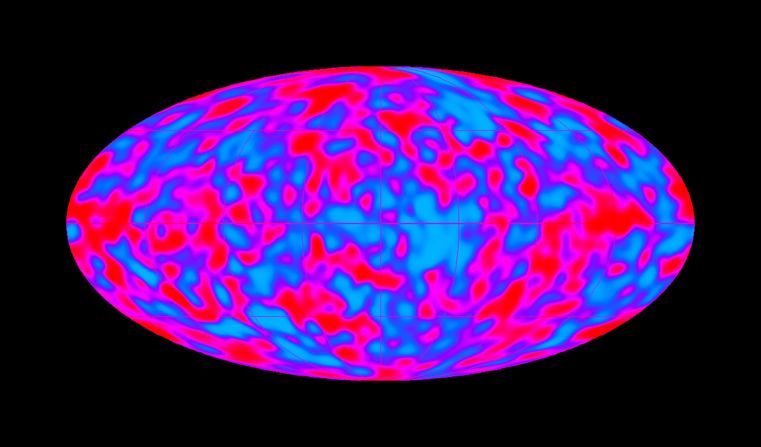

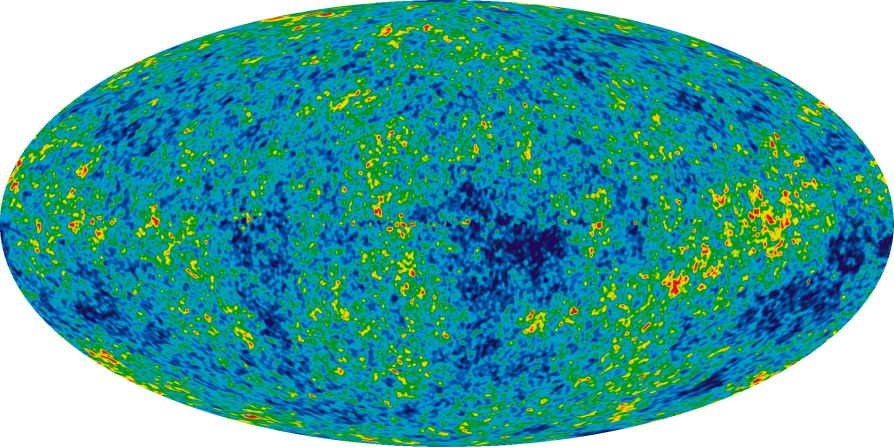

This new photogenic moment, released Thursday, comes courtesy of the European Space Agency’s Planck space telescope, which detects cosmic microwave background radiation – the light left over from the Big Bang. Scientists used data from Planck to create an artificially colored map of temperature variations across the sky in the early universe, in more detail than ever before.

“It’s a big deal,” said Charles Lawrence, Planck project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a news briefing. He added, “We can tie together a whole range of phenomena that couldn’t be tied together so well before, and the sum total of that, the impact, is felt in many, many ways.”

The light is technically from 380,000 years after the Big Bang, but that’s still infancy when you consider that, according to the new data, the age of the universe is about 13.8 billion years.

“By the matching observations from Planck to predictions from models, we can assemble a surprisingly detailed picture of the universe as it was one nano-nano-nano-nanosecond after the Big Bang,” said Marc Kamionkowski, professor of physics and astronomy at John Hopkins University.

Kamionkowski compared the Planck map to the Human Genome Project in terms of its importance for cosmology.

After analyzing the new data, scientists now believe that the universe is about 100 million years older than they thought.

The universe’s light started out as a white hot glow and would have been blindingly bright if anyone had been around to see it, Lawrence said.

But since the Big Bang, that hot light has cooled significantly, and the universe itself has expanded by a factor of 1,100. The light has cooled so much that we can’t see it, but Planck can detect subtle variations in temperature, which give scientists a wealth of information. By subtle, we mean about one-hundred-millionth of a degree.

The colors in the temperature map image that scientists released Thursday were arbitrarily chosen to show these intensity variations, Lawrence said. Red means a little bit warmer than average, blue means cooler than average, and white is average.

Planck data also suggest that our universe has more dark matter than previously thought. A full 26.8% appears to be dark matter, an invisible phenomenon that scientists have only been able to detect indirectly; experiments both in space and at the Large Hadron Collider are hoping to pin it down.

How particle smasher and space telescopes relate

It appears that ordinary matter – all of the stuff that we can see, such as planets and stars – makes up only 4.9% of all the universe.

The rest of the universe is an even more mysterious phenomenon called dark energy, which has also never been detected and appears to be in less abundance than researchers thought.

Scientists said the rate at which the universe is expanding, based on these observations, is 67.15 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a unit of vast distance in space (1 megaparsec = 3.3 million light years). That’s significantly less than what had been calculated previously (73.8 km/sec/Mpc). This number, known as the Hubble constant, describes the acceleration of the stretching of spacetime.

The discrepancy between these Hubble constants will likely attract a lot of attention in the scientific community and is one of the most exciting parts of the new data, said Martin White, a scientist with the Planck mission based at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The hope would be that this is actually pointing toward some deficiency in the models, or some extra physics that we’re not aware of, and maybe spark a whole new research direction,” White said.

One theory that could be explored is that the nature of dark energy, which scientists think is causing the accelerated expansion of the universe, is different from the simplest human-calculated models. Is dark energy increasing with time over some volume of space? That’s a radical theory, though, White said, and there are other possibilities.

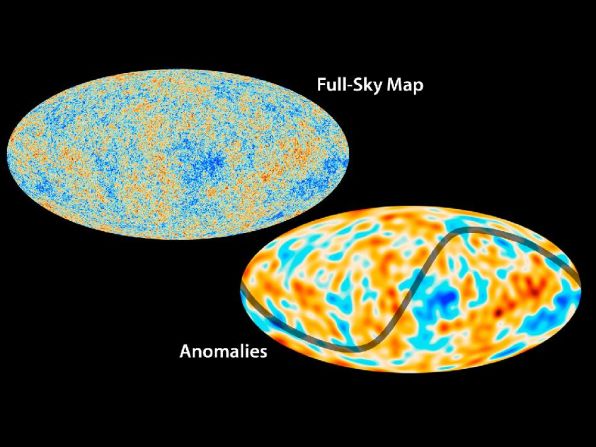

Another anomaly of these results is that temperature fluctuations are not uniform across the sky map. There are more variations in one direction than in another.

“Perhaps we could say that our universe has thrown us a curve ball, and it rarely fails to surprise us,” said Krzysztof Gorski, Planck scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Scientists ran 10 million computer simulations and chose from among them the best match to the new data, White said. Out of those, they found a good match describing important statistics about the universe.

The Planck telescope is aboard a spacecraft that launched in May 2009. It is not circling the Earth but orbits a point in the Sun-Earth system called the second Lagrange point.

The Planck mission helps to nail down many of the parameters that other experiments must know to explore aspects of the universe, such as its expansion history, White said.

New analyses are based on the first 15.5 months of data from this mission, which is run principally by the European Space Agency. NASA is a partner of the project.

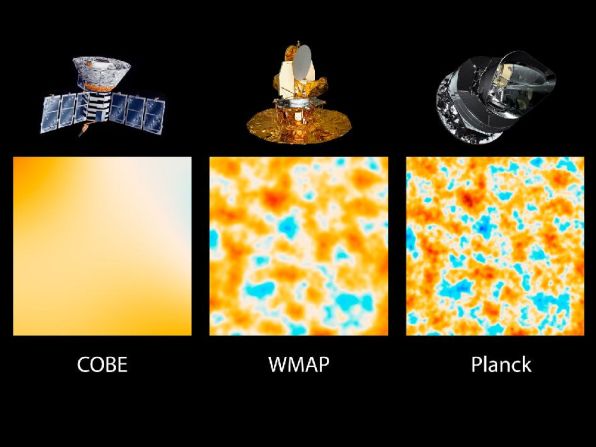

Planck represents the third generation of attempts to map the cosmic microwave background. The first was COBE, launched in 1989, followed by WMAP, launched in 2001. Comparing the resulting maps shows just how much better the maps have gotten with each successive satellite.

“This is a beautiful illustration of how science works,” Lawrence said. “Make a measurement, learn from it, make a better measurement, learn from it.”