Story highlights

Racism in Italian football is a complex issue, highlighting different attitudes

"Ultra" fan groups admit targeting their clubs' black opponents with racial abuse

Anti-racism group says official figures about racist incidents are not accurate

Academic urges football authorities to take stronger action against racist offenders

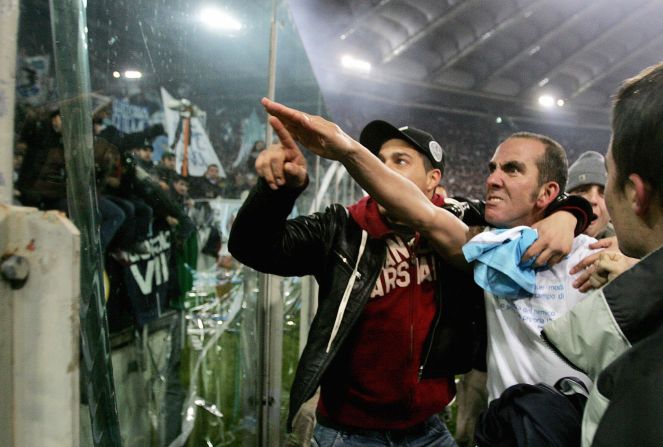

Hardcore Italian football “ultra” Federico is a Lazio supporter who happily admits directing monkey chants at black players.

It is “a means to distract opposition players” says Federico, a member of the Irriducibili (“The Unbeatables”) group which follows the Rome-based team.

“I am against anyone who calls me a Nazi,” Federico told academic Alberto Testa, who spent time “embedded” with Lazio and Roma ultras for the book “Football, Fascism and Fandom: The UltraS of Italian Football,” co-authored by Gary Armstrong.

“What I do not like is people who come to my country and commit crimes; Albanians and Romanians are destroying Rome with their camps,” Federico adds.

“But I’m not a racist. One day, I was waiting in my car at the traffic lights and, as usual, there was a young female gypsy who was trying to clean the car windscreen and was asking for money.

Read: Time for football to tackle racism epidemic?

“Suddenly municipal police officers started to mistreat the girl. I jumped out of my car and almost kicked his arse. I hate injustice.”

There is nothing black and white about Italian football.

Racist abuse has provided the backdrop to the Serie A season, with the latest incident – not for the first time – involving AC Milan striker Mario Balotelli, who was targeted by visiting Roma fans throughout a match at the San Siro Stadium in May.

In the second half referee Gianluca Rocchi called the game to a halt for a few minutes, having warned the crowd via the public address system.

Days after his return to Serie A earlier in 2013, following his move from Manchester City to AC Milan, Italy-born Balotelli was referred to by his new club’s vice president Paulo Berlusconi – the younger brother of the team’s owner and the former Italian prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi – as “the family’s little black boy.”

That remark came after, in what appeared to be an innocuous friendly match against fourth tier Italian side Pro Patria last month, Milan midfielder Kevin-Prince Boateng picked up the ball and kicked it into the stands before tearing off his black-and-red striped shirt and walking off in protest at the persistent monkey chanting to which he and three of his black teammates had been subjected.

In the aftermath of Boateng’s walkout, Italian interior minister Annamaria Cancellieri told Radio 24 that if only a small group of fans were involved in racist chanting, games should not be suspended, but if “a significant part of the fans take part” the game should be stopped “by those responsible for public order.”

Read: African football chief against walkoffs in racism incidents

As Italy grapples with how best to confront racism, it is worth remembering it’s not the only country working out a solution as to how to deal with the problem.

Neo-Nazis and neo-Fascists

This season, matches across Europe have been punctuated by repeated racist outbursts, which have led to calls for world governing body FIFA and European counterpart UEFA to show greater leadership and impose harsher sanctions.

Amid the monkey chants and racial stereotyping, there are no easy answers to the question of just how prevalent is the incidence of racist abuse in Italian football.

According to the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) in Feburary, there have been 50 incidents in Italy of racist abuse over the last six years. Of those 50 cases, 48 relate to racist chanting, with two relating to abusive banners.

“And the total of violent episodes diminished from 209 to 60 and the majority of them happened outside the football venues,” FIGC spokesman Diego Antenozio told CNN.

“The introduction of stewarding has also reduced the need of intervention by police officers inside the venues significantly.”

Read: Boateng makes racism walkout vow

However, talk to the head of Italy’s Observatory on Racism and Anti-racism in Football, Mauro Valeri, who has been monitoring racism in Italian football for over a decade, and a different picture emerges.

His organization estimates there have been over 660 racial incidents since 2000 and puts the number since 2007 at 282, nearly six times as much as the FIGC figure. In all, fines of $5 million have been handed out as punishment in those 660-plus cases, equating to a fine of $7,500 per incident.

“The numbers I record relate to the decision that the judge takes in the sports court and lays down fines and any disqualifications. The FIGC figures concern the criminal law,” said Valeri.

“So in the Boateng case the sports court ruled that Pro Patria had to play the game … ‘behind closed doors’ and were fined $6,689.

“But the ordinary court – the criminal law – has instead decided that those songs were not racist. For me it’s racism, for the Ministry of the Interior, no.”

Valeri added: “In Italy, no club has a real anti-racist strategy, because it believes the fight against racism is not a priority.

Read: Blatter insists FIFA will hit racists hard

“Since the early 1990s, many curves of the stadium have been occupied by neo-Nazi and neo-Fascist groups, but this problem has been addressed only as a problem of public order.”

That is a view that is supported by Italian football writer Charles Ducksbury, a fan of Verona, who added: “The ultra still, and always will hold all the power at clubs. They choose what is sung, what everyone does and how they do it.

“Stewards and police hardly ever enter the curve as they would most likely get beaten up. Ultras say if the authorities stay out the curve, there won’t be any problems. Almost all trouble happens outside the ground anyway, so that’s where police tend to hang around.”

Time warp

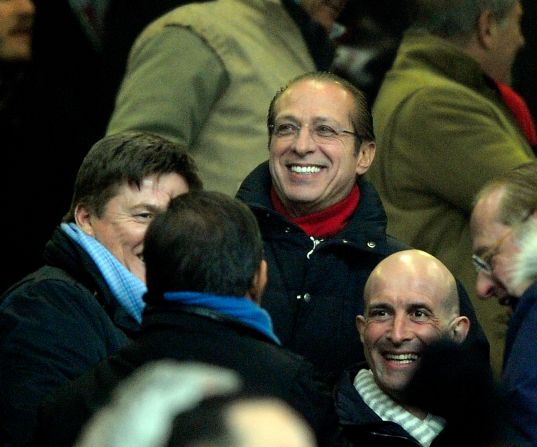

While Boateng walked off, former Netherlands international Edgar Davids, who played for both AC Milan and Inter Milan as well as Juventus, said he felt it was important to show that racist abuse did not affect him as a player during the many years of his career he spent in Italy.

“You would have a problem in certain areas,” Davids told CNN. “But you are a professional, you have an obligation to your team. My opinion was I’m a professional and the smartest way is to play so good that you make them even angrier.

“It is also about ignorance, a fear of the unknown. If you are interested in different cultures, it’s normal.

“If you’re not, you don’t understand that concept. It is not only in Italy and it is not the whole of Italy. It was only certain teams you played, but 80-90% I didn’t have a problem in Italy,” added Davids, though Valeri’s analysis suggests the problem is much more widespread.

Read: U.S. star Altidore suffers racist abuse

If football, race and politics make for a combustible mix in Italy, it is also arguable that the standard of the country’s stadia is not helping.

While English football was forced to grapple with extensive stadium renovation to improve facilities for fans due to recommendations made by Lord Justice Taylor after the deadly crowd disasters at Hillsborough and Heysel in the 1980s, Italian football was left in a time warp.

“I really don’t believe that Italian football has learned the lessons of Heysel and Hillsborough, or at least hasn’t implemented any tangible changes at anything like the pace required,” said another Italian football writer Adam Digby.

“While the Taylor report and formation of the Premier League put English football at the forefront of fan safety and gave it ultra-modern stadia almost throughout the league, Serie A still plays host to a number of ancient, decrepit grounds.

“Many are still those built for Italia ’90 with places such as Verona’s Bentegodi and the San Paolo in Naples particularly poor on both counts.

“The problems extend to a lack of quality stewarding and lax ticket security while the ultras bring even greater problems to the situation.”

Read: Lazio fans charged with racist behavior

Owen Neilson, who is writing a book about Italian football stadia – “Stadio: The Life and Death of Italian Football” – concurs that the lack of stadium redevelopment has held back Italian football. Of Serie A’s big clubs, only Juventus has built a new stadium, he notes.

“The modernity of the stadia is the central issue to declining attendances – families do not want to sit in the cold, unfriendly surroundings,” said Neilson.

“In my opinion the league needs to harness to new stadiums to help maximize Serie A’s re-emergence.”

So what’s the solution?

“The FIGC makes a relevant anti-racism activity both in the national and international domain according to the UEFA policy and guidelines, and is member of anti-discrimination organization Football against Racism in Europe,” said the Italian Football Federation in its statement to CNN.

“Specific guidelines are part of National License Club System’s requirements, as are the anti-racism initiatives that are made through FIGC Youth & School Department to involve 860,000 young footballers.”

But as Italian historian John Foot, author of the authoritative book on Italian football “Calcio” points out: “The Italian authorities have been all over the place on racism for a long time.”

Racist chants

Valeri, meanwhile, urged the FIGC to donate the racism fines it recoups from the clubs for initiatives against racism, as does UEFA in its work with FARE.

“Any solution has to revolve around the football authorities,” added Professor Clifford Stott, who has advised governments and police forces internationally on crowd management policy and practice.

Stott calls on FIFA and UEFA to do more.

“The FIGC, FIFA and UEFA must empower fan-based initiatives that are capable of creating a culture of self-regulation. The anti-racism agenda has come a long way in the last decades.

“By walking off Kevin-Prince and his fellow players have forced the agenda. The high-level political support for his action now means this might happen again, but this time during a much higher profile game – perhaps even in the Champions League. The authorities have to react to this potential.”

But Stott also warned against an indiscriminate reaction by the authorities.

“We have learned a great deal about crowd management since the Heysel disaster, and there must be recognition that it is not appropriate or constructive to sanction whole crowds,” he said.

“The approach to security must be capable of differentiating between those fans that are acting illegally and those fans that are not. Failure to recognize this and to react indiscriminately runs a very real danger of escalating not reducing the problems.”