Story highlights

- Armstrong says he told his son: "Don't defend me anymore"

- He says he deserves punishment, but not the "death penalty"

- Part two of Armstrong's interview with Oprah Winfrey aired Friday night

Legendary and now disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong told Oprah Winfrey during a confessional interview that he hopes to compete again.

"If you're asking me do I want to compete again, the answer is hell yes. I'm a competitor," Armstrong said during the second part of a two-part interview, which aired Friday on Winfrey's OWN channel and online.

"I can't lie to you. I'd love the opportunity to be able to compete, but that isn't the reason that I'm doing this. Frankly, this may not be the most popular answer, but I think I deserve it," he said.

In part one of the interview, which aired Thursday, Armstrong admitted, unequivocally and for the first time, that he used performance-enhancing drugs on the way to seven Tour de France wins.

When asked whether he felt disgraced, Armstrong said that he did.

"But I also feel humbled. I feel ashamed. This is ugly stuff," he said during the second part of the interview.

Armstrong, who has been stripped of his Tour de France titles and an Olympic bronze medal, blamed no one but himself for his doping decisions, and was careful not to implicate others.

"I deserve to be punished," Armstrong told Winfrey. But, he said: "I'm not sure that I deserve a death penalty," comparing his punishment to the lesser punishments of other cyclists who doped.

"I'm not saying that that's unfair necessarily, but I'm saying it's different," Armstrong said.

The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency hit Armstrong with a lifetime ban after the agency issued a 202-page report in October that said there was overwhelming evidence he was directly involved in a sophisticated doping program.

Armstrong, in the first part of the interview, talked about the culture of cycling at the time he competed, telling Winfrey that doping was widespread then and just as much "part of the job" as water bottles and tire pumps. The former cyclist said he didn't view using banned drugs then as cheating. "I viewed it as a level playing field."

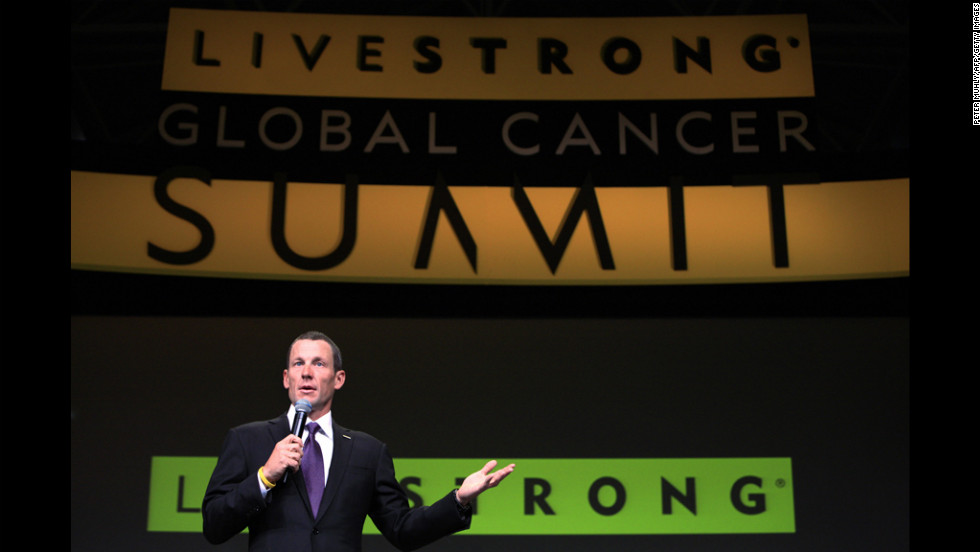

The scandal has tarred the Livestrong cancer charity that Armstrong founded and brought an end to his endorsement deals.

He described to Winfrey stepping down from that charity, which he characterized as his "sixth child." That moment, he said, was his most humbling.

"To make that decision and to step aside was -- that was big," he said in Friday's broadcast. "It was the best thing for the organization, but it hurt like hell."

Armstrong told his son: Don't defend me anymore

Throughout both parts of the interview with Winfrey, Armstrong spoke steadily and showed little emotion.

That changed when Armstrong spoke about his family, and especially his kids.

Appearing to hold back tears, Armstrong said he confessed to the three oldest children over the recent holiday break. "The older kids need to not be living with this issue in their lives," the athlete said. "It isn't fair."

Speaking specifically about his 13-year-old son, who he had heard defending him, Armstrong said he told the youth: "Don't defend me anymore."

During the first part of the interview, Armstrong described himself as "deeply flawed" and "arrogant," and spoke often of how so much was his "fault."

"I was a bully," he told Winfrey of how he treated others who might expose him.

But Armstrong was not telling the whole story, author David Coyle, who wrote a book about doping and the Tour de France, told CNN's Anderson Cooper on Thursday night.

"A partial confession is sort of the pattern here," he said. "Maybe this is Armstrong's partial, and more will come out later."

The cyclist denied pushing teammates to dope, an assertion Coyle countered.

"Tyler Hamilton gets a phone call: Be on a plane tomorrow. We're flying to Valencia to do a blood transfusion. That's what happens," Coyle said.

Armstrong described his years of denial as "one big lie that I repeated a lot of times." He had races to win and a fairy tale image to keep up.

He reminisced on his storied past of being a hero who overcame cancer, winning the Tour repeatedly, having a happy marriage, children. "It's just this mythic, perfect story, and it isn't true," he said.

Former teammate: More needs to happen

Former cyclist Tyler Hamilton, who raced as a teammate of Armstrong from 1998 to 2001, said it was nice to hear Armstrong own up to some of his faults.

Hamilton was among those who broke from Armstrong and decried his use of performance-enhancing drugs. Armstrong at the time denied the allegations and threatened him with legal action.

"He's made the first step," Hamilton told CNN's Piers Morgan before the second interview aired. "There are many more steps to come for Lance Armstrong."

According to Hamilton, the next step for the disgraced cyclist is to testify before cycling officials about the doping network, naming names as needed.

The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, which tests Olympic athletes for performance-enhancing drugs, similarly described the interview as a "small step in the right direction."

"If he is sincere in his desire to correct his past mistakes, he will testify under oath about the full extent of his doping activities," USADA CEO Travis Tygart said.

The International Cycling Union called it "disturbing" to see Armstrong's confessions, but it said the sport is much different today than it was 10 years ago.

"Lance Armstrong's decision finally to confront his past is an important step forward on the long road to repairing the damage that has been caused to cycling and to restoring confidence in the sport," union president Pat McQuaid said.

Years of success and defiance, then a rapid fall

After winning various legs of the Tour de France, Armstrong's sporting career ground to a halt in 1996, when he was diagnosed with cancer. He was 25.

He told Winfrey that he then developed a "ruthless and relentless" attitude that helped him survive. But he carried it with him into his sports career, "and that's bad," he said.

He returned to the cycling world, however. His breakthrough came in 1999, and he didn't stop as he reeled off seven straight wins in his sport's most prestigious race. Allegations of doping began during this time, as did Armstrong's vehement defiance.

He left the sport after his last win, in 2005, only to return to the tour in 2009.

Armstrong still insists he was clean when he finished third that year, but that comeback led to his downfall.

"We wouldn't be sitting here if I didn't come back," he told Winfrey.

In 2011, Armstrong retired once more from cycling. But his fight to maintain his clean reputation continued. Federal prosecutors launched a criminal investigation, but it was dropped in February.

In April, the USADA notified Armstrong of an investigation into new doping charges. In response, the cyclist accused the organization of trying to "dredge up discredited" allegations and filed a lawsuit in federal court trying to halt the case.

Those who suffered for speaking out now feel vindicated.

They include Betsy Andreu, wife of fellow cyclist Frankie Andreu, who said she overheard Armstrong acknowledge to a doctor treating him for cancer in 1996 that he had used performance-enhancing drugs.

"This was a guy who used to be my friend, who decimated me," Andreu told CNN's Anderson Cooper on Thursday night. "He could have come clean. He owed it to me. He owes it to the sport that he destroyed."

The former athletic icon conceded he'd let down many fans "who believed in me and supported me."

"I will spend the rest of my life ... trying to earn back trust and apologize to people."