Editor’s Note: David Nolan is associate professor of meteorology and physical oceanography at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami.

Story highlights

David Nolan: As far as hurricanes go, the storm we call "Sandy" is not very intense

Nolan: There are two elements that make Sandy unusual, possibly even "super"

He says Sandy's right-to-left pathway is atypical, as is its intact hurricane core

Nolan: Sandy will take its place in history, but we'll have to wait until it's over to know where

As far as hurricanes go, Sandy is not particularly intense. With peak winds at 90 mph Monday at 5 p.m., it is still classified as a Category One, with only a small chance of briefly achieving the low end of Category Two before making landfall somewhere in New Jersey on Monday evening.

And yet, state and local governments have gone into full alert mode, with schools closed, cities shut down, and evacuations ordered across the Eastern Seaboard. Justifying the alarm are enormous waves arriving onshore, raising the mean water level by a few feet even here in Miami, where the winds are blowing directly offshore.

Sandy could bring ‘catastrophe,’ affect 60 million

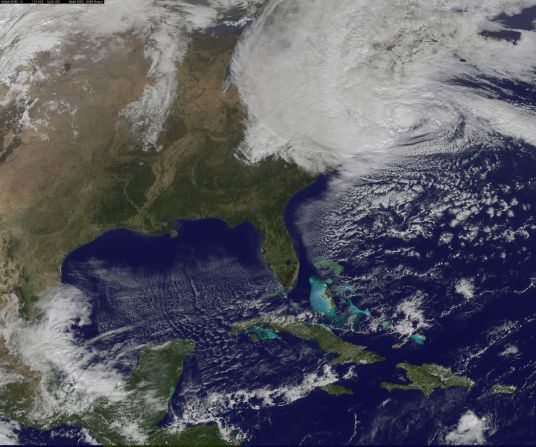

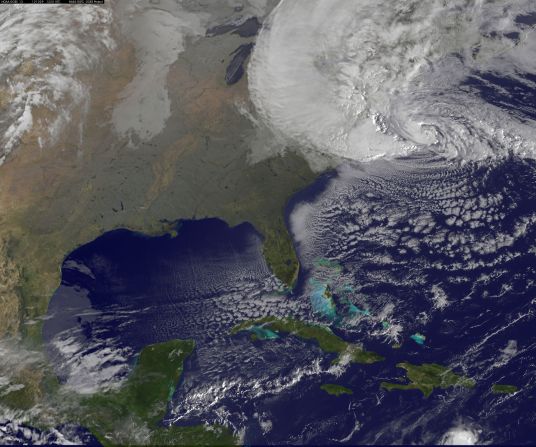

Sandy represents the confluence of a modestly strong hurricane coming up from the Caribbean and a fairly strong but not unusual continental weather system – what meteorologists call a “trough” or “dip” in the jet stream – that has been traversing the country over the last few days.

In the vast majority of cases, these weather systems weaken hurricanes while at the same time pushing them quickly out to sea. Such weather systems also generate their own cyclones, not as intense as hurricanes, but larger and slower moving.

Opinion: As Sandy descends, tips from Katrina survivors

Get our free weekly newsletter

When these extra-tropical cyclones form over the ocean and move along the coast, we call them nor’easters (for the strong northeasterly winds they generate). Sometimes, tropical and extra-tropical systems merge, and the hurricane turns into a large ocean cyclone. But again, almost all of these storms move quickly out to sea.

There are two elements that make Sandy very unusual, possibly even “super.”

First is its pathway. Rather than racing out to sea like most coastal storms, Sandy has already turned hard to the left and it will make landfall at nearly a right angle to the U.S. coastline. This extremely unusual track (from right to left) means that almost every piece of coastline from New Jersey to Cape Cod will receive onshore winds at some point during the event.

Second, the core of Sandy – the part that will look and feel like a hurricane – has remained intact, even as cooler and drier air from the United States wraps around it. Thus, Sandy has each of the worst features of both kinds of storm: a small core of hurricane-force winds around its center, and a broad expanse of gale-force winds extending hundreds of miles outward that will batter the shorelines for several days.

Why did this happen?

It was simply a matter of positioning.

Sandy arrived east of Florida at exactly the right time and place to get the maximum benefits from its interaction with the dip in the jet stream. As a result, Sandy became large enough to influence that system as well, and the two will wrap around each other into a single, deep cyclone, 800 miles across, extending from the ground to 40,000 feet in the sky. This will add to the duration of the event as the circulation takes several days to wind down over Pennsylvania and New York.

Opinion: Climate change raises stakes for coast

As for whether Sandy is a “Superstorm,” perhaps we should refrain from such a designation until after the event.

There was already a “Superstorm” in March 1993 – a nor’easter that dumped snow from New Orleans to Canada. There was the Halloween Storm of 1991 – later known as the Perfect Storm – which, like Sandy, also grew from the confluence of a large extra-tropical cyclone and a hurricane (which, unlike Sandy, was destroyed in the process). And there was the Blizzard of ’78, the Eastcoaster of 1996, and others.

Sandy will take its place in history, but we will not know what that place is until many days have passed.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of David Nolan.