Story highlights

NEW: Armstrong's lawyer says witnesses should have been cross examined

Armstrong has long denied using performance-enhancing drugs

Former teammate testified Armstrong use a drug called EPO, report says

Other teammates said they were shown how to avoid positive drug tests

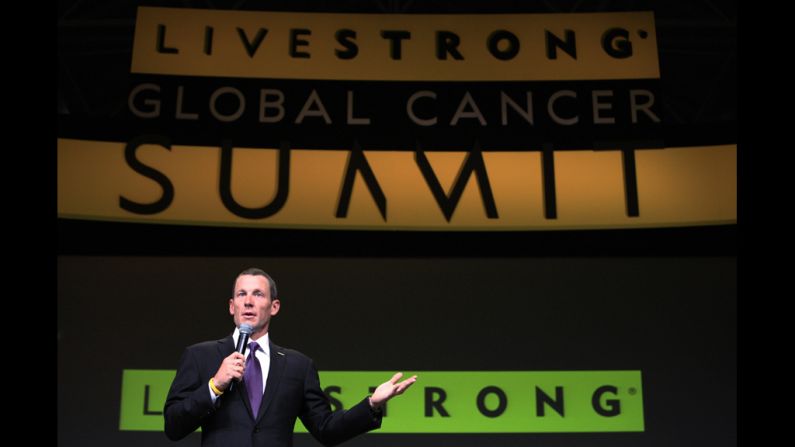

Cyclist Lance Armstrong was part of “the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that sport has ever seen,” the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency said Wednesday in releasing more than 1,000 pages of evidence in the case.

The evidence involving the U.S. Postal Service-sponsored cycling team encompasses “direct documentary evidence including financial payments, e-mails, scientific data and laboratory test results that further prove the use, possession and distribution of performance-enhancing drugs by Lance Armstrong,” the agency said.

Armstrong lawyer Tim Herman dismissed what he called a “one-sided hatchet job” and a “government-funded witch hunt” against the seven-time Tour de France winner, who has consistently denied doping accusations.

Armstrong teammates recount dodging, tricking drug testers

But the USADA said 11 riders came forward to acknowledge their use of banned performance-enhancing drugs while on the team. Among them is George Hincapie, Armstrong’s close teammate during his winning Tour de France runs.

“I’m not suggesting that they are all lying, but I am suggesting that each witness needs to have confrontation and cross examination to test the accuracy of their recollection,” Herman said.

The USADA is sending its “reasoned decision” to the international governing body of cycling, the Union Cycliste Internationale, as well as the World Anti-Doping Agency and the World Triathlon Corporation, which runs Ironman competitions.

Highlights of the Armstrong report

In the past, Armstrong argued that he has taken more than 500 drug tests and never failed. In its 202-page report, the USADA said it had tested Armstrong less than 60 times and the UCI conducted about 215 tests.

“Thus the number of actual controls on Mr. Armstrong over the years appears to have been considerably fewer than the number claimed by Armstrong and his lawyers,” the USADA said.

The agency didn’t say that Armstrong ever failed one of those tests, only that his former teammates testified as to how they beat tests or avoided the test administrators altogether. Several riders also said team officials seemed to know when random drug tests were coming, the report said.

The agency also said it had a professor compare Armstrong’s red cell and plasma levels from blood samples taken late in his career, and they showed levels that wouldn’t be expected of an athlete competing in a three-week endurance event like the Tour de France.

What’s behind the Armstrong headlines

Hincapie publicly admitted for the first time Wednesday that he took drugs.

“Early in my professional career, it became clear to me that, given the widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs by cyclists at the top of the profession, it was not possible to compete at the highest level without them,” Hincapie said in a written statement. “I deeply regret that choice and sincerely apologize to my family, teammates and fans.”

Hincapie testified, the report said, that he was aware of Armstrong’s use of the drug EPO, or erythropoietin, which boosts the number of red blood cells, which carry oxygen to the muscles, and his use of blood transfusions.

He also testified Armstrong dropped out of a race in 2000 to avoid a positive drug test, according to the report, which was accompanied by hundred of pages of supporting documents like Hincapie’s 16-page affidavit.

Three members of the Postal Service team, which changed sponsors in 2005, will contest the accusations, the agency said. They are team director Johan Bruyneel, team doctor Pedro Celaya and team trainer Jose “Pepe” Marti. Each will get a hearing before an independent judge, according to the agency.

The agency compiled the evidence as part of its investigation into doping allegations that have dogged Armstrong and the Postal Service team for years. The organization is not a governmental agency but is designated by Congress as the country’s official anti-doping organization for Olympic sports.

In August, four days after a federal judge dismissed Armstrong’s lawsuit seeking to block the agency’s investigation, Armstrong announced he would no longer fight the accusations. The agency then announced it would ban Armstrong from the sport for life and strip him of his results dating from 1998.

“When Mr. Armstrong refused to confront the evidence against him in a hearing before neutral arbitrators, he confirmed the judgment that the era in professional cycling which he dominated as the patron of the peloton was the dirtiest ever,” the USADA writes in its decision. “Peloton” refers to the main group of riders in a bike race.

Armstrong: It’s time to move forward

The agency praised the 11 riders who came forward to document the widespread use of banned substances by the team. But in a statement issued Wednesday afternoon, attorney Herman called the expected USADA report “a taxpayer-funded tabloid piece rehashing old, disproved, unreliable allegations, based largely on axe-grinders, serial perjurers, coerced testimony, sweetheart deals and threat-induced stories.”

In addition to Hincapie, the agency identified the cyclists who came forward as Frankie Andreu, Michael Barry, Tom Danielson, Tyler Hamilton, Floyd Landis, Levi Leipheimer, Stephen Swart, Christian Vande Velde, Jonathan Vaughters and David Zabriskie.

The agency said those riders would receive various punishments, including suspensions and disqualifications.

The scope of evidence against the team is “overwhelming,” according to the agency.

“The USPS Team doping conspiracy was professionally designed to groom and pressure athletes to use dangerous drugs, to evade detection, to ensure its secrecy and ultimately gain an unfair competitive advantage through superior doping practices,” the agency said.

Your Armstrong questions answered

Armstrong became a household name not only in Europe, where cycling is wildly popular, but also in the United States, where the sport traditionally attracted little attention before he embarked on a remarkable stretch between 1999 and 2005 and won seven consecutive Tour de France titles. Persistent accusations that he used performance-enhancing drugs grew as he won more Tours.

Author and cycling journalist Bill Strickland compared the case to baseball’s “Black Sox” scandal, when eight Chicago White Sox players conspired with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series. But he said Armstrong is “not interested in ever admitting to his guilt, and he just wants to move on right now.”

“Despite this evidence and despite all the evidence that has come out, he’s got a strong core of people who believe in him and will always believe in him because of his link to fighting cancer,” said Strickland, who chronicled Armstrong’s 2009 return to the Tour de France in a 2011 book.

Opinion: Armstrong and the tenuous nature of heroism

But how Armstrong might move on is unclear.

“Certainly, he’s not going to be able to move on within the sport,” Strickland told CNN. “It seems likely that all of his Tour victories will be stripped. He won’t be allowed to participate in any sports that are signatories of WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency. But he’s found a few triathlons to do in the meantime.”

And he said the allegations could lead to the reopening of a criminal case against Armstrong that federal prosecutors closed without charges in February.

“What’s next is years and years of fighting if the criminal case is reopened,” Strickland said.

The USADA opened its own case, which does not carry criminal penalties, in June.