Watch “Crisis in Syria: Inside Aleppo” on CNN at Saturday and Sunday at 7 p.m.

Story highlights

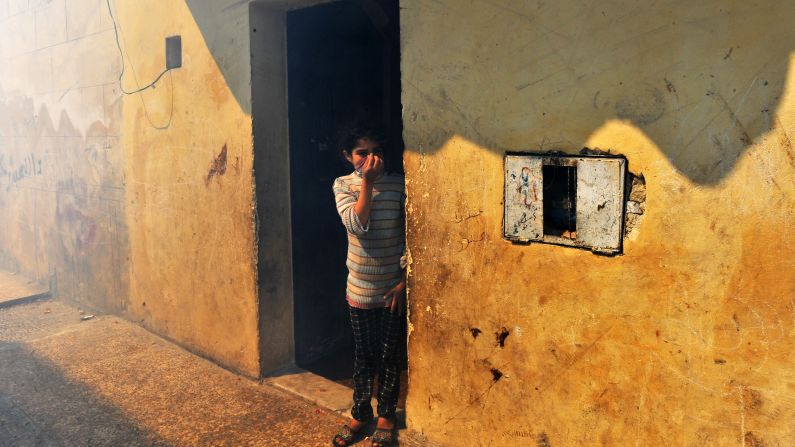

Children have become some of the main casualties during the Syrian civil war

Every hour, medical staff face dilemmas on how to ensure patients can be saved

Doctor: Regime soldiers with worst, perhaps unsurvivable, injuries are given lethal injections

Injured children are carried across front line to ensure better care in government hospitals

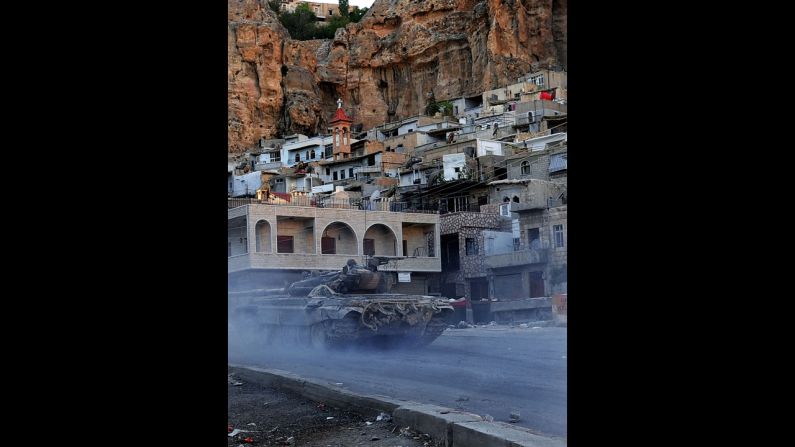

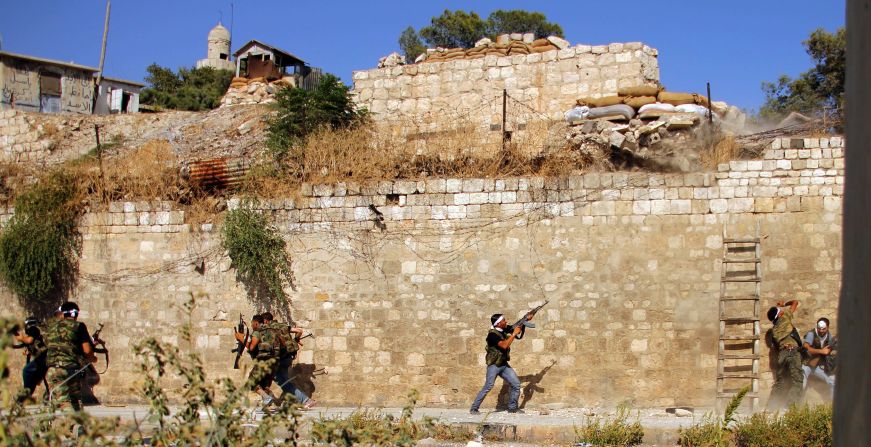

They are so used to seeing blood outside Dar alShifa hospital, the magnet of all suffering in Aleppo, that passersby simply walk over it, oblivious. When they mop out the building’s tiny reception area, the blood runs in small, dirty streams into the gutters. This is a hospital trying to get by day-to-day while lacking the most basic in supplies. It has itself been hit by shelling: two separate attacks have left its right side punctured with gaping holes in what was once the maternity ward.

One afternoon, a rush of the most frail and vulnerable come towards the exhausted doctors; children, some suffering from sheer terror. One is malnourished. They have cuts, bruises – but more often much worse. The government has, the doctors say, closed the main children’s hospital owing to a paperwork issue, so this is where they must come.

Baby survives as family dies in Syrian onslaught

Mohamed is aged eight and was hit by shrapnel from regime shelling in his right leg. It shattered his femur. In Europe, surgery would mean he’s playing football again within months, but here a list of precarious challenges form. He remains quiet, brave, patient almost, as the doctors work out what to do.

The tough natural solution they hit on is a stark reminder of how desperate the task is of getting medical care to the wounded here in rebel-held territory. The government hospital has better equipment, and can probably save Mohamed’s leg. So, lifting him on the blankets they use as makeshift stretchers, they take him, bewildered and confused, into a nearby taxi to cross the front lines. His ordeal is far from over. It is perverse to know that only those who hurt him can also heal him.

A Syrian family’s desperate story

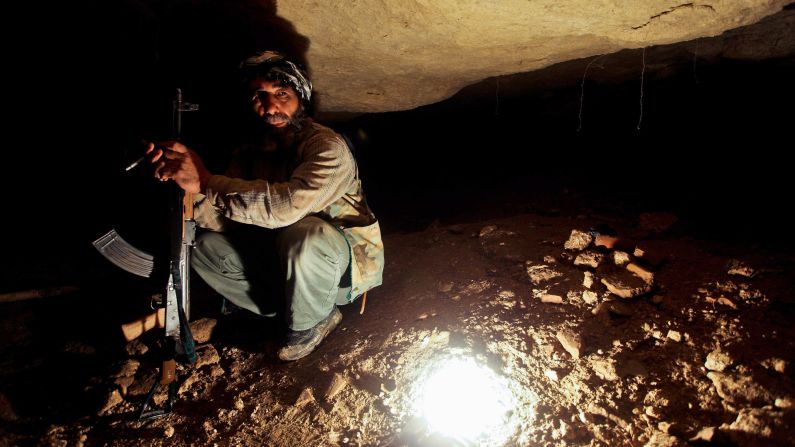

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose face adorns plastic skeletons used as teaching aids and trash cans inside Dar alShifa, still controls the best hospitals and much of the most precious medical resource: doctors. One medic, terrified enough that he doesn’t want his face or voice on camera, is absurdly brave in the risks he takes every day to work in Dar alShifa. During the morning and afternoon, he works in the government hospital. But later, he too crosses the Line to come here.

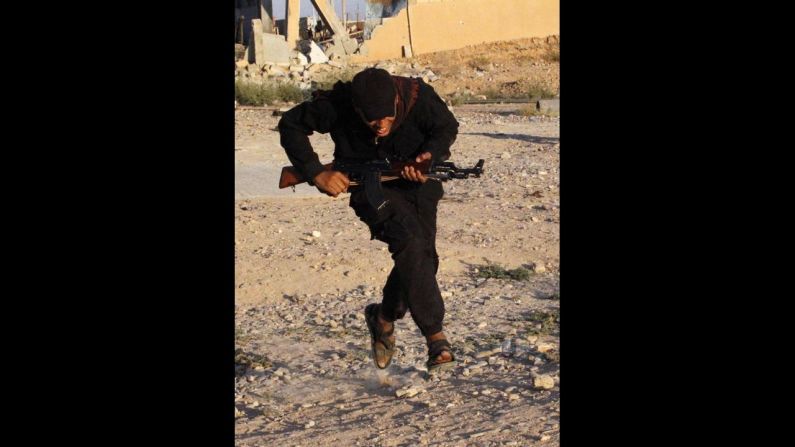

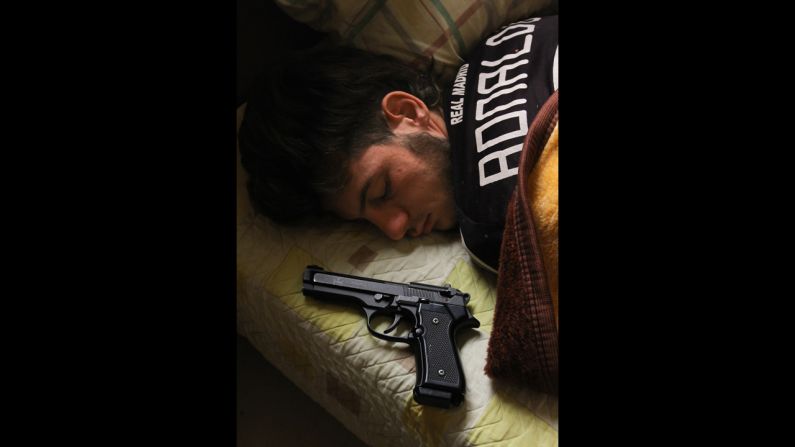

He paints a gruesome picture of caring for the Syrian regime’s soldiers. Fifty a day are brought in, he tells me. Some are so wounded the doctors make a decision, he says, that sounds like it is born of mercy and perhaps rebel sympathies. Those soldiers with the worst, perhaps unsurvivable, injuries are given lethal injections. He tells me: “If they found out I was working here, they would kill me.”

Slain journalist’s partner tells of grief

Suddenly, a truck arrives outside and little Ahmad is rushed inside. His right ear is hanging on only by a small thread of skin. Shrapnel – as indiscriminate when it lands as the means by which it is fired – hit the back of his head.

The doctors work to clean the wound, but, as too often is the case, the lights and power fail. He lies there as a doctor with a head torch tries to pull the shrapnel from his head. The anesthetic they gave is not enough to stop him screaming in pain.

But this is not the worst that will befall Ahmad. As he lies there, outside in the back of a truck slumps his father Yahya, lifeless, a hole in his chest from the same shrapnel. “Allahu Akbar” cry the men around his corpse. “God is great.” They leave his body in the sidewalk until his brother arrives. Later his family will quickly drive the body away, so Ahmad can learn of his father’s death at a more dignified time.