Editor’s Note: Each month, Inside the Middle East takes you behind the headlines to see a different side of this diverse region.

Story highlights

Syria's uprising has politicized and emboldened the country's artists

They say they have moved beyond fear, although they now face greater dangers

A protest singer's throat was cut and a cartoonist's hands broken

A major exhibition of Syrian political art is currently on display in Amsterdam

With horrors emerging from Syria’s civil war with numbing regularity, it can be easy to lose sight of the fact that the uprising has not been waged only with guns.

A creative and resolutely non-violent form of opposition to Bashar al-Assad’s regime has taken hold in Syria, as the country’s artists respond to the crisis with newfound boldness and purpose, despite the clear dangers in doing so.

“Since the uprising, the artists have broken through the wall of fear in Syria and are thinking in another way,” said Syrian journalist Aram Tahhan, one of the curators of an exhibition on Syria’s creative dissent – Culture in Defiance – currently on display in Amsterdam.

“The uprising has changed the artists’ thinking about the task of art in society, how they can do something useful for society,” said Tahhan. “They have rewritten everything.”

With works spanning from painting to song to cartoons, puppet theater to graffiti to plays, the exhibition traces the way that Syrian artists have used a range of creative techniques within traditional and new media to create political, populist art that that both brooks “the red line” of dissent and engages the public in unprecedented ways.

The regime is well aware of the power of visual images and art to mobilize public opinion, says Tahhan. After all, the uprising began when schoolchildren in Daraa were arrested for painting anti-government graffiti on the walls of a school last year.

“From the beginning the regime has known it’s dangerous to use the image, to use art,” said Tahhan. “The camera is the equal of any weapon from the point of view of the regime.”

A dangerous calling

All of which has made producing political art dangerous, sometimes mortally so. Ibrahim Qashoush, a fireman and part-time poet from Hama, wrote popular anti-Assad songs that were sung demonstrations, most notably a number called “Time to Leave.”

Last July, his body was found dumped in a river with his throat cut out, vocal cords removed. A pen-and-ink portrait of the mutilated singer by artist Khalil Younes is featured in the exhibition, while Qashoush’s song is played in a section the curators call the “Revolutionary Hit Parade.”

Read also: Images of Tahrir – Egypt’s revolutionary art

The regime’s brutality has struck more established artists as well.

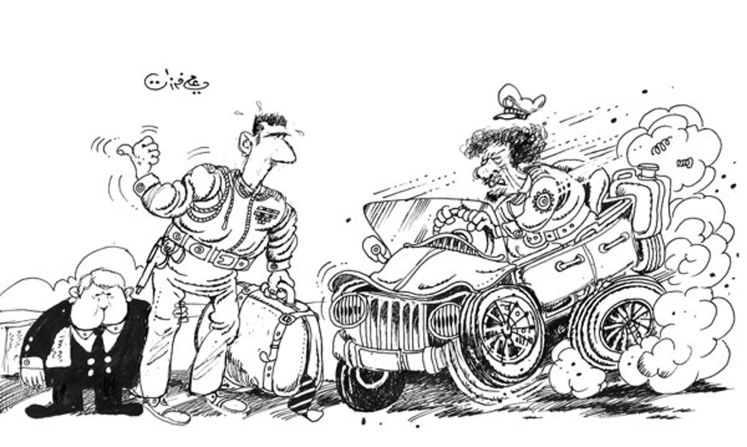

The distinguished political cartoonist Ali Ferzat had his first piece published in a newspaper when he was 12, produced a daily editorial cartoon for the official newspaper throughout the 1970s, and had direct contact with Bashar al-Assad throughout the early days of his presidency.

“I remember when he first walked into my exhibition at a cultural centre – a tall dude with a large entourage. He asked me how he could access what the people were thinking and I told him to just talk to them,” Ferzat said, in an interview printed in the exhibition’s catalog.

Ferzat’s cartoons had typically used symbols, and rarely depicted identifiable political figures. But three months before the uprising began, hoping to inspire others, he resolved to take a more strident approach.

Writing a call to arms on his website – “We have to break the barrier of fear that is 50 years old” – he began drawing senior regime figures, before breaking the final taboo by depicting Assad himself.

“It was a decision that took a lot of guts, but I felt it was time. No one could take their corruption anymore,” he said.

In August 2011, he said he was abducted by gunmen and brutally assaulted, his attackers focusing their violence on his hands.

Ferzat has left the Syria to recuperate, but like many others in his position, has vowed to continue working and to return to his country.

“I just started drawing after healing,” he said. “After I was assaulted and my hands were broken, someone asked me: Could I still find the courage to draw? I told them I had been ashamed by the suffering of 13-year-old Hamza al-Khateeb. I am humbled by the culture and heart of people who cannot draw or write but who are sacrificing their lives for freedom.”

A technological revolution

Not only are the artists of the Syrian uprising expressing political views more boldly than before, but they are employing new technologies to bring those works to a broader audience, engaging the public with art in an unprecedented way.

Before the uprising, said Tahhan, art tended to be the preserve of only a relatively small circle of urban Syrians. “But since, we have had a new kind of cultural production – new songs, new theater, new cinema, new posters that make links between the artistic and the ordinary life of the people. Most of artists are concerned with what happens in the street: Checkpoints, the daily life of the people under tough conditions.”

Read also: Tourists take Islamic “pray-cations”

Syria has poor internet infrastructure – although this is changing slowly – while censors have typically been wary of social media sites, according to press freedom organization, Reporters Without Borders. But under Bashar al-Assad, the regime had been increasing its visibility on the web. In February 2011, shortly before the uprising began, Facebook was unblocked, and before that al-Assad and First Lady, Asma had their own pages on the site.

According to Tahhan, Facebook and social media sites like it provided activists with a powerful medium for distributing subversive images.

One piece of resistance art which has thrived on the internet, gaining hundreds of thousands of views online, is the daring satirical puppet show Top Goon: Diaries of a Little Dictator, created by the 10-member artists’ collective Masasit Mati.

The leader of group – drawn from theater, art, film-making and journalism backgrounds – said he settled on finger puppets for their depiction of Assad and his regime because they were easy to smuggle through checkpoints, and because doing so removed the “godlike aura” around Assad.

“He’s a puppet; you can carry him in your hand,” the group’s anonymous director, Jameel, told curators. “You can break him. You can actually deal with everything that is scary with laughter.” Syrians have begun referring to Assad using the name of Top Goon’s diminutive dictator, Beeshu, he added. “It’s peaceful, effective protest.”

Syria explained: What you need to know

Documentary through art

For other artists, their work has also played an important role in documenting a conflict that has largely been shielded from the world’s media by the regime.

Khalil Younes, the painter, illustrator and video artist behind the portrait of Qashoush, believes the relative absence of journalists in Syria makes it incumbent on artists to capture the unfolding events.

“We saw hundreds of thousands of professionally taken photographs of the Egyptian revolution,” he told curators. “As artists, we should make something that not only reflects on the (Syrian) revolution right now, but make something that will last two generations from now.”

The uprising “isn’t just a people standing up to their government, to the regime; it is a revolution with many aspects: An artistic revolution and a social one as well,” he said.

“Significantly, you can see people trying to introduce sensitive ideas to the public; and it seems they are receptive, which itself is a sign of social change.”

Christa Meindersma is the director of the Prince Claus Fund, the Dutch culture funding body behind the exhibition.

She said the exhibition, which runs at the Prince Claus Fund Gallery until late November and is curated by Malu Halasa, Tahhan, Leen Zyiad and Donatella Della Ratta, was attracting interest from galleries around the world wanting to represent Syrian artists.

The exhibition “really gives a different picture to what is going on, in addition to what we see on television,” she said. “Which is of course also a reality, but this is a reality – a very important one.”

Attendees are often surprised by the diversity of the work being produced, and by the humorous, subversive tone of many artists, she said.

“It is very difficult for civilian artists and activists right now who want to work non-violently while there is so much violence going on,” she added. “Yet there’s a large dose of humor, notwithstanding the situation. They say they have moved beyond fear.”

Follow the Inside the Middle East team on Twitter: Presenter Rima Maktabi: @rimamaktabi, producer Jon Jensen: @jonjensen, producer Schams Elwazer: @SchamsCNN, writer Tim Hume: @tim_hume and digital producer Mairi Mackay: @mairicnn