Story highlights

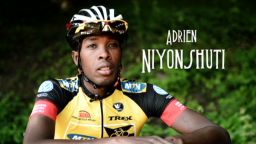

Adrien Niyonshuti carried Rwandan flag at opening ceremony of 2012 Olympics

Six of his brothers were killed in the Rwandan Genocide of 1994

The 25-year-old will compete in the men's mountain bike final on Sunday

He has received coaching from mountain bike great Thomas Frischknect

Adrien Niyonshuti is unlikely to win an Olympic medal, and he will do well to even finish his event, but his story is surely one of the most inspirational in the history of the Games.

In April 1994, when he was just seven, Niyonshuti’s family became victims of the brutal genocide in Rwanda which left nearly 800,000 people slaughtered.

He fled the Hutu killers who came to his village, but six of his brothers were murdered and up to 60 of his wider family perished.

He miraculously escaped with his mother and father, living off scraps in the countryside, almost starving to death before aid came in the form of the rebel Tutsi army from neighboring Uganda.

“The memory of the genocide is a really hard time for me and for a lot of people in Rwanda,” he told CNN’s Human to Hero series.

“Cycling gives me the opportunity to keep my past time away and really focus on what I want to do.”

Read more: Rwanda’s wooden bike riders

Not only did he survive one of the worst atrocities in modern history, but Niyonshuti has overcome the odds to carry his country’s flag at London 2012.

He will have to wait until the final day of the Games before he can actually compete, but the fact that the 25-year-old from the small east African country has qualified for the men’s mountain bike final is an achievement in itself.

A way forward

Black African competitors are few and far between in this highly technical discipline, which is dominated by riders from the traditional powerhouses of cycling in Europe.

Lack of specialist equipment and top-class competition are almost insurmountable barriers to even the most physically gifted athlete such as Niyonshuti, but by finishing fourth in last year’s African Mountain Bike Championships he booked his place on the starting line at Hadleigh Farm.

As he grew up, initially encouraged by his uncle Emmanuel, who lent him an old steel bike, Niyonshuti used cycling as an escape from the realities of his past.

But youthful enthusiasm can only take you so far in any sport, particularly from a war-ravaged country with little competitive structure.

Niyonshuti’s life changed when he was noticed by a trio of top international riders who came to Rwanda to help with a local race: Jonathan “Jock” Boyer, the the first U.S. cyclist to compete in the Tour de France in 1981; fellow international competitor Tom Ritchey; and Swiss mountain bike legend Thomas Frischknecht.

They all spotted Niyonshuti’s raw talent and set about giving him the chance to achieve his potential.

See also: From war child to U.S. Olympic star

Team Rwanda

Boyer returned, having secured some funding in the United States and backing from cycling’s world governing body, the UCI.

His goal was to set up Team Rwanda and, based in Ruhengeri, in the north east of the country, he tested young prospects for their physical capabilities.

As Boyer remembers, Niyonshuti stood out from the rest.

“He tested higher than than anyone, but his whole demeanor was different, really dedicated to what he wanted to do,” Boyer told CNN.

The veteran retired pro and young hopeful even raced together in the 2007 Cape Epic – the Tour de France of mountain bike racing – and finished a creditable 33rd overall and top Rwandan pair.

Yet Niyonshuti and his teammates were concerned that Boyer and other helpers would eventually leave them.

” ‘How long is this going to last?’ they asked me. In a country like Rwanda they were well used to aid projects which lasted for about six months and then departed.”

But Boyer stayed, helping Niyonshuti to achieve his potential in a professional team.

Professional contract

He contacted Douglas Ryder, the boss of South Africa’s MTN-Qhubeka and after a trial Niyonshuti was signed in 2008.

What followed has been the stuff of dreams, and in 2009 Niyonshuti became the first black African to compete in a professional peloton when the team raced in the Tour of Ireland.

Not only that, he was introduced to seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong, who was also in the stage race that year as he returned from his first retirement.

Niyonshuti quickly realized that although Armstrong was a legend, the American was still flesh and blood like everyone else.

“When I saw him on the news, I thought Armstrong was a big, big man!” he recalled. “But when I saw him face to face, he was quite small!”

Niyonshuti has excelled in road racing and individual time trialing against the clock, but cross-country mountain biking offered him the best chance of Olympic qualification.

After gaining his spot, he has been honing his skills with Frischknecht in Switzerland, staying at the former world champion’s home.

“His technical skills were poor but he was very strong,” said Frischknecht.

At the Olympics, seeded riders start in the front rank, giving them a massive advantage on the narrow and highly technical course.

Olympic goal

For riders like Niyonshuti, who will be starting towards the back, the aim of the game is to avoid being lapped and therefore eliminated, which is no easy task.

“We have one big goal: to actually finish the race,” Frischknecht confided.

“He can only afford to be about 10 minutes behind the leader, but I have some hope he can actually do it. He has developed his skills a lot.”

So no Olympic glory, just survival, but Niyonshuti’s life has been all about just that and his efforts will hopefully inspire a generation of cyclists from his country.

Boyer has no doubt of that.

“Each country always has a hero and Adrien for Rwanda is the ignition point, the spark that is going to get kids into cycling,” he said.

Longer term, Boyer believes Niyonshuti can prosper in the professional peloton and one day ride the Tour de France with MTN, which wants to acquire a higher UCI pro continental team status next year.

“They have a two-year plan to achieve it,” Boyer said.

Flag bearer

MTN has signed 20-year-old Ethiopian Tsgabu Grmay, as well as two Eritrean riders, Meron Russom and Jani Tewelde, so it is not inconceivable there could be sizable African representation in the greatest cycling race in the world.

Given Niyonshuti’s tragic past, it would complete a remarkable journey for him – and if sheer determination was the only factor, he will surely take his place.

“I will never give up, I will try my best,” is Niyonshuti’s racing philosophy.

He will be putting it to the test against the best mountain bikers in the world as the London Olympics come to a climax on Sunday.

Having already carried Rwanda’s flag at the opening ceremony, Niyonshuti knows that the hopes and dreams of his nation rest on his slim shoulders – and he will surely not let them down.