Editor’s Note: Peter Bergen, CNN’s national security analyst, is a director at the New America Foundation. His book “Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden; From 9/11 to Abbottabad” will be published on May 1. Jennifer Rowland is a program associate at the New America Foundation, a Washington-based think tank which seeks innovative solutions across the ideological spectrum.

Story highlights

Authors: America's drone war in Pakistan is much diminished

They say it's a victim of a deeply troubled relationship between U.S., Pakistan

U.S. raid on bin Laden and other incidents sparked anger from Pakistanis, they say

Drones have killed many al Qaeda leaders, and some targets are low level, they say

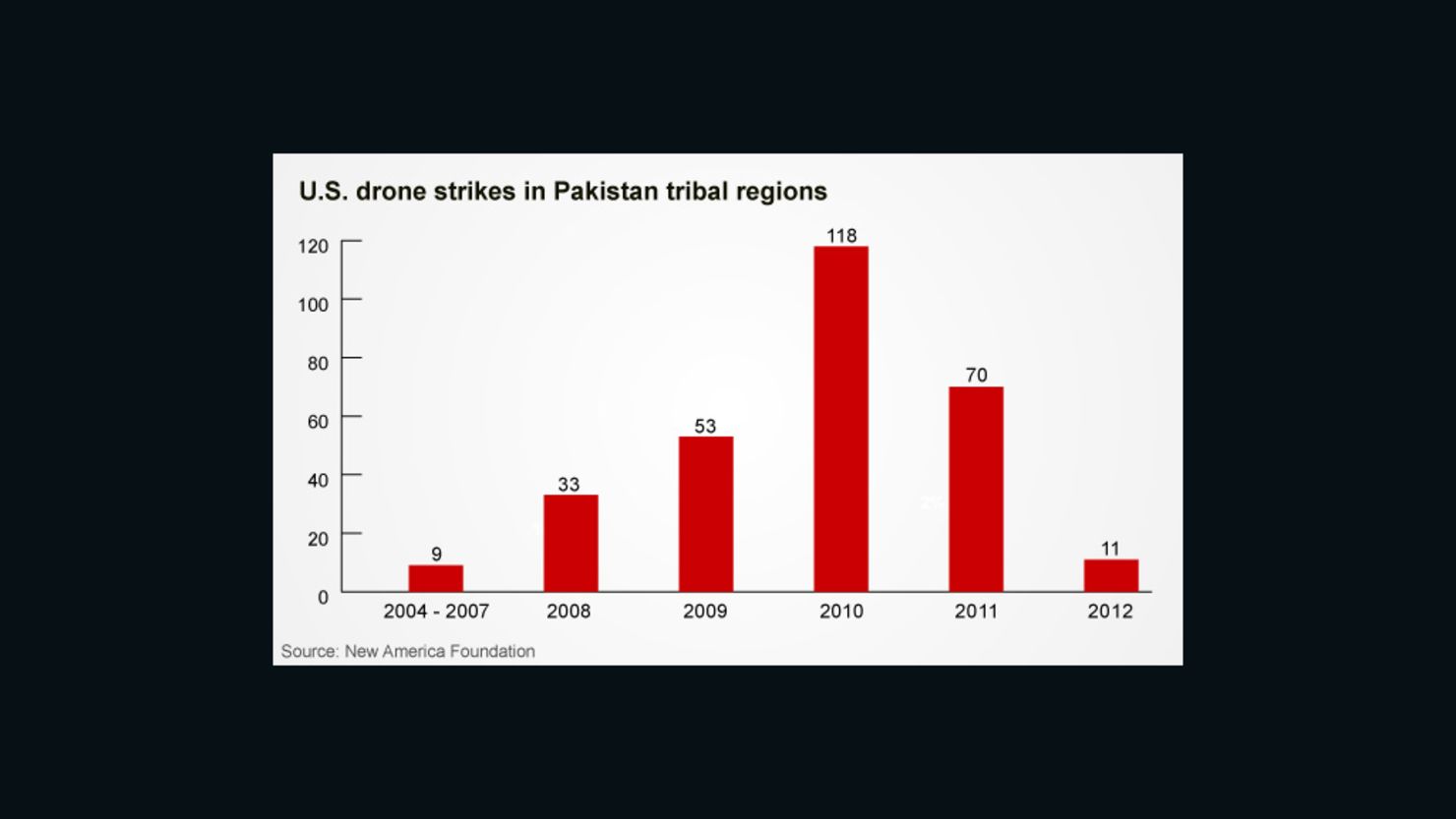

The past year has seen the number of CIA drone strikes in Pakistan plummet. In the first three months of 2012, there were 11, compared with 21 in the first three months of 2011 and a record 28 in the first quarter of 2010.

On Monday, Pakistan’s parliament started to debate whether the United States should be made to stop CIA drone strikes altogether in the Pakistani border regions with Afghanistan and also whether the U.S. should apologize for NATO airstrikes that killed some two dozen Pakistani soldiers late last year.

Given the high level of hostility to the United States in Pakistan, the results of the parliamentary debate are pretty much a foregone conclusion. The parliament will almost certainly vote against the allowing the continuation of the drone strikes and will also demand an American apology for the deaths of its soldiers.

Obama calls for balanced approach on U.S.-Pakistan relations

The debate in parliament comes as relations between the U.S. and Pakistan have reached a nadir, caused by a wave of incidents over the past year that have poisoned the two countries’ already often troubled relationship:

– The killing of two Pakistanis by a CIA contractor in January 2011.

– The unilateral U.S. attack on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad four months later.

– The airstrikes by NATO in November that killed the Pakistani soldiers.

That incident caused Pakistan to close its borders to trucks resupplying NATO soldiers in Afghanistan.

At 2 a.m. November 26, two Pakistani border posts about half a kilometer from the Afghan border came under heavy fire from NATO helicopters that had strayed across the border into Pakistani airspace.

Pakistani officials immediately termed the attack, which killed 26 Pakistani soldiers, a “deliberate act of aggression,” while U.S. officials maintained that the Pakistani security officials had fired on the helicopters first.

Either way, the friendly fire incident was devastating, not least to the U.S. drone program in Pakistan’s tribal regions, which was subsequently suspended for almost seven weeks, one of the longest pauses in the strikes since the program started in 2004. Pakistan also ordered the United States to vacate Shamsi Air Base in Balochistan, from which many of the CIA drones were launched.

For many months before this incident, the United States’ aggressive drone campaign in Pakistan had been slowing. There were 70 drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal regions in 2011, down from 118 in 2010, which saw the peak number of strikes since the program began.

The drop in drone strikes during 2011 was because a series of events that wore on the ever-fragile U.S.-Pakistan relationship. On January 27, 2011, an American citizen, Raymond Davis, shot and killed two Pakistanis who he said were attempting to rob him in the streets of Lahore.

Despite U.S. claims of diplomatic immunity because of Davis’ employment at the U.S. consulate in Lahore, he landed in jail, charged with a double murder and illegal weapons possession. Much of the Pakistani public was outraged when it was revealed in February that Davis was a CIA contractor.

As a result of the complex negotiations to get Davis out of Pakistani jail, there were just three CIA drone strikes in February and another nine strikes in March while U.S. officials worked to settle the issue and finally bring Davis home.

The day after Davis was finally released, a strike on March 17, 2011, killed a reported 36 civilians, as well as a top Taliban commander. Pakistani officials condemned the strike, and Pakistanis took to the streets to protest them. The CIA suspended drone strikes for a month, before resuming them again on April 13.

Less than a month after the drone strikes had picked up, on May 1, U.S. Navy SEALs secretly flew into Pakistani territory aboard stealth helicopters to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, who was living not far from the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.

Pakistan’s powerful military establishment was angry about the violation of its sovereignty, and relations between the U.S. and Pakistan sank further. For their part, many Americans were outraged that al Qaeda’s leader had been living for years in a sizable city in central Pakistan.

Aware of how unpopular the drone strikes were becoming in Pakistan, some top U.S. Defense and State Department officials behind the scenes were pushing for more selective drone strikes, which the CIA opposed.

The White House ordered an evaluation of the drone program during the summer of 2011. The study found that the CIA was primarily killing low-level militants in its drone strikes.

Those results prompted the government to implement new rules in November governing when and how specific drone strikes were authorized. The State Department was given a larger say in the decision-making process. Pakistani leaders were promised advanced notification of some strikes. The CIA pledged to refrain from conducting strikes during visits by Pakistani officials to the United States.

But the new rules are unlikely to placate critics inside and outside of Pakistan, who condemn the violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty and the killing of its civilians.

At the New America Foundation, we maintain an up-to-date database of every reported drone strike in Pakistan’s tribal regions since 2004. We monitor reports about the strikes from the top Western and Pakistani news sources, such as The New York Times, Associated Press, CNN, Reuters, Express Tribune, Dawn, Geo TV and others.

According to our data, 7% of the fatalities resulting from drone strikes in 2011 were civilians, up 2 percentage points from our figure in 2010. Over the life of the CIA drone program in Pakistan from 2004 to 2012, we found that the civilian casualty rate has been 17%.

Clearly, as the years have progressed, the drone strikes have become more precise and discriminating. There is still considerable debate over how the U.S. government defines a “militant” and how easily it is able to distinguish between militants and civilians from a drone cruising tens of thousands of feet above the ground.

In March 2011, Maj. Gen. Ghayur Mehmood acknowledged that “the number of innocent people being killed is relatively low” and that “most of the targets are hard-core militants,” the first such public acknowledgment by a senior Pakistani military officer.

Similarly, President Barack Obama made his first public comments about the covert drone program, when he told participants of a Google+ “hangout” on January 30 this year that the United States only conducts “very precise precision strikes against al Qaeda and their affiliates, and we’re very careful in terms of how it’s been applied.”

Even if it is the case that there are relatively few civilians killed in the strikes, the drone program is quite unpopular in Pakistan.

The New America Foundation conducted one of the few public opinion polls in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas during the summer of 2010 and found that almost 90% of the respondents in the region where the drone strikes are located oppose U.S. military operations in the region.

The wider Pakistani public shares this sentiment, though to a lesser degree. A poll conducted by the Pew Research Center in June 2011 found that about six of every 10 Pakistanis consider the drone campaign to be unnecessary.

Despite the fact that the pace of drone strikes slowed considerably from 2010 to 2011, the number of strikes last year still ranked as the second-highest annual count since the drone program began.

And despite its deteriorating relations with Pakistan, the United States killed a number of key al Qaeda leaders with drone strikes in 2011. Al Qaeda’s top operative in Pakistan and purported conduit between the terrorist group and the Pakistani Taliban, Ilyas Kashmiri, was reported killed in a strike on June 4.

Then, on August 22, a drone reportedly killed al Qaeda’s top operational planner, Atiyah Abd al-Rahman, dealing another heavy blow to the organization. And in September, a drone strike killed Abu Hafs al-Shihri, the man believed to be responsible for planning al Qaeda’s operations in the region.

The continued success of strikes against al Qaeda’s top leaders led Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to declare in July that the United States was “within reach of strategically defeating al Qaeda.”

According to senior U.S. counterterrorism officials, al Qaeda’s leadership bench has been so thinned by the drone campaign that there are only two real leaders of the organization left: bin Laden’s successor as overall leader of the group, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Abu Yahya al-Libi.

This raises an interesting question: Maybe one of the reasons that the drone campaign has eased off in the past several months is that the CIA has begun to run out of real targets?

Follow us on Twitter: @CNNOpinion

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion