Story highlights

California forcibly sterilized 20,000 people from 1909 to 1963

The goal was to rid society of people labeled "feeble-minded" or "defectives"

California's response to victims stands in stark contrast to North Carolina's

Ex-lawmaker: Californians need to face their history and hold hearings

Six decades ago, Charlie Follett was a teenager living in California’s Sonoma State Home. As he did most days, Follett sat in a field, singing popular songs to himself, enjoying the sunshine and the solitude.

Suddenly, someone came outside to get Follett and brought him to the hospital. They told him to lie down on an operating table, and then the needle came out.

“First, they shot me with some kind of medicine. It was supposed to deaden the nerves,” he said. “Then the next thing I heard was snip, snip, and that was it.”

The doctors didn’t tell Follett what they were doing, but he knew anyway. Other boys at the Sonoma State Home had told him how much it hurt to have a vasectomy. Now it was his turn.

“When they did (my right side), it seemed like they were pulling my whole insides out,” said Follett, now 82 and living in Stockton.

California: Leader in forced sterilizations

Follett was one of 20,000 Californians forcibly sterilized by the state from 1909 to 1963.

The goal was to rid society of people thought to be undesirable: people labeled “feeble-minded” or “defectives.”

“It’s one of the most horrific and shameful chapters in California’s history,” said Los Angeles civil rights attorney Areva Martin.

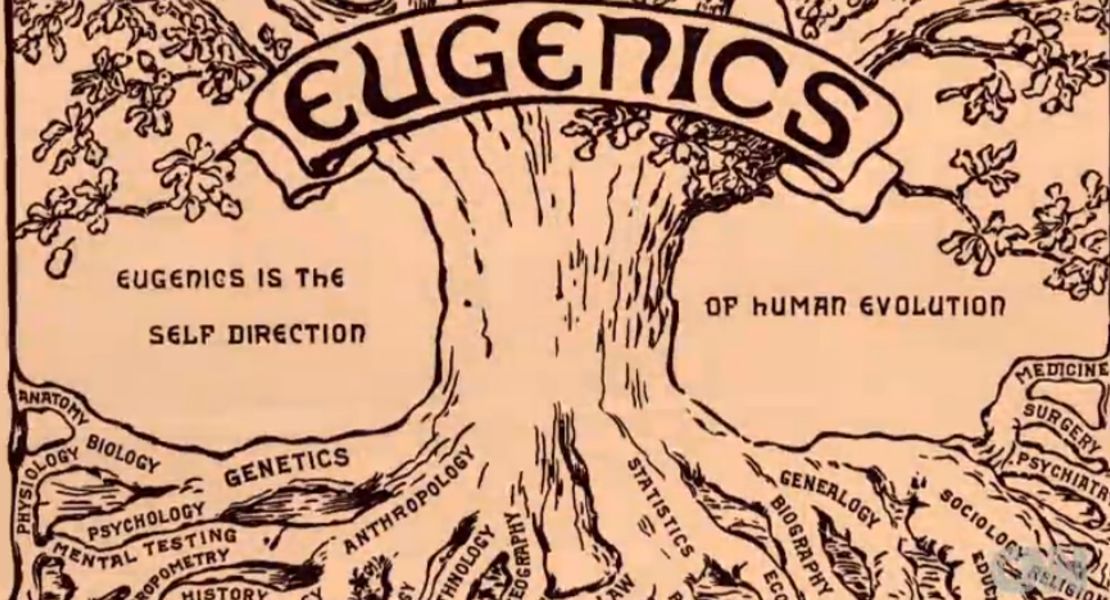

Thirty-two states had eugenics programs, but California was in a league of its own.

The Golden State sterilized more than twice as many people as the next state, Virginia, which sterilized 8,300, according to Paul Lombardo, a professor at Georgia State University’s College of Law.

The law said that wards of the state like Follett had to be sterilized in order to be discharged from institutions like Sonoma, according to Christina Cogdell, a cultural historian at the University of California-Davis and author of “Eugenic Design.”

Men and women, boys and girls, were sent to state institutions for all sorts of reasons. Some had serious developmental disabilities. Follett ended up at Sonoma because his parents were alcoholics and couldn’t care for him.

In the mid-20th century, the country’s intellectual elite such as doctors, geneticists and Supreme Court justices supported forced sterilizations.

In California, the eugenics movement was led by figures such as William Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University, and Harry Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times.

In other states, the sterilization program would stop and start due to legal challenges, but California’s ran strong for more than half a century, Cogdell said.

“If you were deemed worthy of being sterilized by a doctor, there was no board where you could have a hearing to protest,” he said.

California’s movement was so effective that in the 1930s, members of the Nazi party asked California eugenicists for advice on how to run their own sterilization program.

“Germany used California’s program as its chief example that this was a working, successful policy,” Cogdell said. “They modeled their law on California’s law.”

“It kills my last name”

In 2003, then-Gov. Gray Davis apologized for the forced sterilizations, but Follett wants compensation for not be able to have children of his own.

“What really ticks me off is, it kills my last name,” Follett said. “If I should die tomorrow, everything’s died.”

Over the past few years, a friend of Follett’s has tried to help him seek justice. Rudy Banlasan, a nursing student, has written letters and e-mails on Follett’s behalf to Gov. Edmund “Jerry” Brown and other state politicians and officials.

He has not succeeded in getting any of them to speak with him. Banlasan keeps a file of the e-mails he’s sent to politicians and the form letters he’s received in return.

“I hate to sound so cynical, but I think they’re just waiting for the victims to die and forget this whole thing ever happened,” Banlasan said.

“There’s nothing more to add”

CNN’s attempts to contact politicians have been unsuccessful.

The governor’s office referred CNN to the state Department of Developmental Services, which sent a two-sentence statement: “The State of California deeply regrets the harm caused to victims of involuntary sterilization that occurred through the first half of the 1900s. This was a sad and painful period in California’s history, one that should never be repeated.”

When CNN asked Brown for his stance on reparations for sterilization victims, press secretary Gil Duran sent an e-mail referring to the statement. “There’s nothing more to add,” he wrote.

CNN also sent e-mails and made phone calls to the office of John Perez, speaker of the California Assembly. When no response was received, CNN visited his office in Sacramento. His spokesman, John Vigna, said the speaker was tied up in meetings.

“This is an issue I personally am just learning about and looking into,” Vigna said.

California’s response to victims stands in stark contrast to North Carolina’s.

North Carolina task force recommends $50,000 for sterilization victims

In that state, Gov. Bev Perdue has sought out victims and held hearings where she apologized personally and heard their stories.

She also set up a task force to help the victims and recommended that each receive $50,000 in reparations.

“That’s not happening in California,” said Martin, the civil rights attorney. “To think that we’re behind on this issue instead of leading on this issue is very troublesome.”

“California has not done right”

Art Torres is the former California state senator who wrote the 1979 legislation outlawing sterilization.

He said he’s not surprised politicians are reticent on the subject.

“I would venture to say most people in this legislature – and most people in California – aren’t even aware there was a eugenics movement in California,” Torres said.

Californians, he added, need to face their history and at least hold hearings and invite victims to tell their stories.

“California has not done right by these victims,” Torres said. “But I think California and Californians need to be aware of their history.”

CNN’s Lindsey Bomnin contributed to this story.