Story highlights

The case raises questions about the effect of eyewitness IDs on a jury

Man appealed his conviction, saying the eyewitness testimony should have been thrown out

Many factors can distort eyewitness identifications, experts say

Barion Perry was detained at the crime scene, handcuffed after being suspected of breaking into cars. Without specifically being asked by police to identify the suspect, a neighbor pointed out Perry from a nearby window as the alleged thief.

It was left to the Supreme Court Wednesday to decide whether that identification was overly suggestive and therefore unreliable, violating the due process rights of the defendant.

During an intense hour of oral arguments, several justices debated whether the narrow facts of this case might open the legal floodgates to a range of new exceptions of evidence jurors would be excluded from hearing at trial.

“What about an eyewitness identification from 200 yards?” said Justice Antonin Scalia, raising one of several hypotheticals by him and his colleagues. “Normally you’d leave it to the jury and the jury would say that’s very unlikely. But you want to say it has to be excluded and if it’s not, you retry the person. What is special about (police) suggestiveness as opposed to all of the other matters that could cause eyewitness identification to be wrong?”

“From the criminal defendant’s point of view, it doesn’t really much matter whether the unreliability is caused by police conduct or by something else,” countered Justice Elena Kagan.

The appeal raises larger questions about the unique power of eyewitness identifications to sway jurors, and whether innocent people are unfairly being sent to prison, particularly to death row. The court has not taken a hard look at the issue since 1977.

The unique facts of the Perry case could leave a clear rule on the boundaries of using unreliable identification evidence even more elusive and muddled, despite the high court’s current intervention. Several justices said Perry’s lawyers presented strong evidence and that reforms may be necessary, but others on the bench wondered whether such changes are mandated under the Constitution, and if they would apply in other areas of criminal justice where evidence is problematic.

The incident happened in August 2008 in Nashua, New Hampshire. A black male was reported at the back of an apartment parking lot in the middle of the night. A city police officer arrived and found Perry carrying two amplifiers, which he claimed he found on the ground.

An apartment resident then approached police and said his car was broken into, information relayed by his neighbor. While Perry was detained in the parking lot, that officer went to the apartment to interview the neighbor. When asked to describe the suspect, she said it was a “tall black man,” but offered no other physical details. When asked by the officer for more information, the neighbor looked back and said “it was the man that was in the back parking lot standing with the police officer,” according to court records.

Later at the police station, the female neighbor was unable to identify Perry from a photo lineup.

Perry was then arrested, subsequently convicted of theft, and given a three- to 10-year prison term. He appealed, saying the eyewitness testimony should have been suppressed. Subsequent state courts rejected his claims that due process protections apply even when the suggestive circumstances were not “intentionally orchestrated by the police.”

During arguments, Perry’s lawyer Richard Guerriero said his client’s prosecution was a “miscarriage of justice.”

“Police suspicion is the kind of influence that would direct the witness’s attention and say that’s the man,” he told the court.

“I don’t know what you want the police to do in this case,” said Justice Anthony Kennedy, hinting police would be criticized either way when seeking out witnesses to identify the suspect. “It seems to me it would have been, A: risking this argument from the defendant, and B: improper police conduct, not to ask the woman, ‘Is this the man?’”

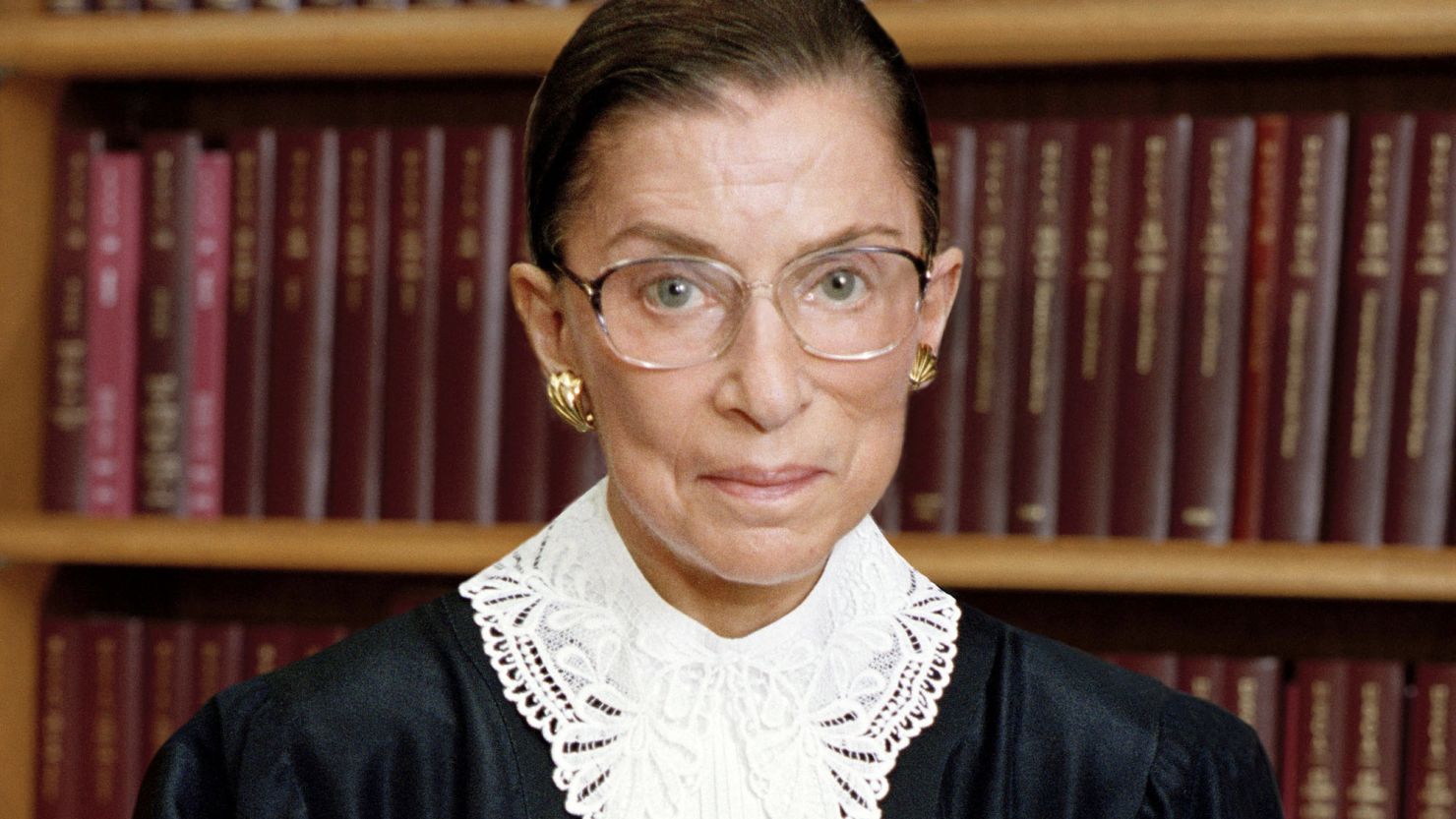

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg suggested a hard rule excluding eyewitness testimony from trial may not be practical or necessary. “What about all the other safeguards that you have?” she said. “You can ask the judge to tell the jury: Be careful – eyewitness testimony is often unreliable. You can point that out in cross-examination.”

“You’re just usurping the province of the jury, it seems,” added Kennedy.

Citing another hypothetical of a crime that led to the suspect’s being shown in a newspaper photograph, Justice Samuel Alito asked Guerriero: “You want to make it possible for the judge to say that (a) victim may not testify and identify the person that the victim says was the perpetrator of the rape, on the ground that the newspaper picture was suggestive, even though there wasn’t any police involvement and when you look at all the circumstances, the identification is reliable. Now, maybe that’s a good system, but that is a drastic change, is it not, from the way criminal trials are now conducted?”

After the solicitor general of New Hampshire presented the state’s case, a Justice Department lawyer further warned about expanding due process rights on the broad category of the reliability of evidence.

Nicole Saharsky suggested if the court did that, “defendants throughout the United States (would be) making arguments about all different kinds of evidence not involving the police being unreliable,” opening the floodgates to endless litigation.

“There surely is some minimal due process requirement for the admission of evidence, isn’t there? Are you saying there is none?” asked Alito, saying the state could put a witness on the stand “who says this person did it because I saw it in my crystal ball.”

Eyewitness identification has been closely scrutinized by a range of legal groups and social scientists – some 2,000 empirical studies, in fact, over the past three decades, according to one legal brief filed with the high court. It has also become a staple of crime dramas: a witness rises from the stand, points to the defendant and says “That’s the man who did it, I’m sure, your Honor.”

But not always. A variety of all-too-human factors can distort, manipulate, or mislead a person’s memory, whether spurred by police involvement or not. A new book by law professor Brandon Garrett called “Convicting the Innocent” found the initial 250 DNA exonerations around the United States came about after 190 of the prisoners were convicted based on mistaken eyewitnesses.

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution mandates the government not “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” That has led to a long line of jurisprudence over what areas of the criminal justice system are covered by the broad provision.

The conservative high court majority two years ago said inmates could not go to court to demand, under due process, DNA testing to establish their innocence. “We are reluctant to enlist the federal judiciary in creating new constitutional code of rules for handling DNA,” said Chief Justice John Roberts, suggesting that was best left to legislatures.

The eyewitness case is Perry v. New Hampshire (10-8974). A ruling is expected within the next few months.