Story highlights

- How Islam will fit with democracy is a hot topic following the Arab Spring uprisings

- Strict and moderate forms of Islam are discussed in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia

- Turkey's democracy is seen as a model by some

It's not often that the issue of polygamy makes it to the top of the political agenda. But in the past week it's become a litmus test for the course of the Arab spring, and part of the debate about the compatibility of Islam and democracy.

Declaring that Libya was liberated, interim Prime Minister Mustafa Abdul-Jalil said last Sunday that laws restricting polygamy would be nullified. Islamic Shariah law would be the basic source of legislation, he said, and new banks would comply with Islam's prohibition of interest and speculation.

A few days later, Rachid Ghannouchi -- leader of the Islamist Ennahda party in Tunisia -- said he would not propose changing laws that ban polygamy and provide equal rights for men and women in marriage and divorce. Nor would western-style banking be curbed.

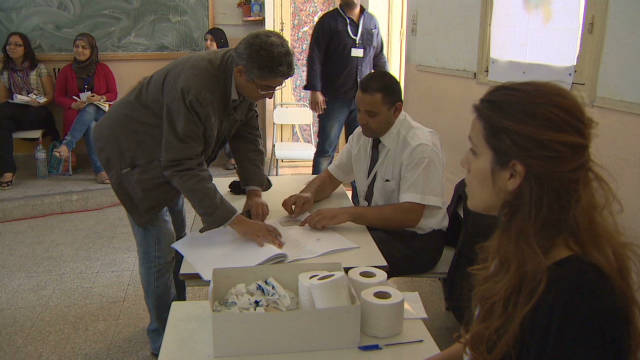

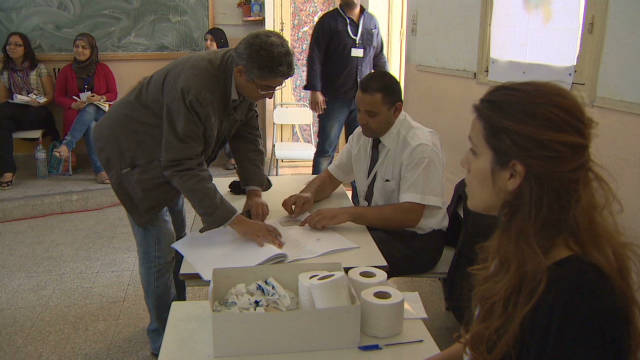

Ghannounchi's views matter. Ennahada emerged from the first election of the Arab Spring last weekend as Tunisia's largest party, with 90 of the 217 seats in the constituent assembly that will write a new constitution.

Jalil sought later to downplay his remarks, telling the world's media that Libyans were moderate Muslims, though some analysts believe his original remarks were a nod toward a more radical strain of Islam that has emerged with the Libyan uprising.

As authoritarian rule is thrown off or challenged in Arab countries, ideas for a new political model pour into the vacuum. The West will be hoping that Ghannouchi's template becomes the model rather than a less tolerant embrace of Shariah -- the religious law of Islam. Ennahda has already reached out to secular groups to form a coalition.

"The whole region is heading toward a moderate Islam and an Islam which is democratic, through the reconciliation between Islam and modernity," the Wall Street Journal quoted him as saying.

Some Tunisians -- mainly among the better off urban middle-class -- don't believe Ennahda's professed moderation. A series of videos released online ahead of the election (and paid for by wealthy business interests) imagines a Tunisia without tourists, where women are made to wear the veil and are scared out of the workplace, should Islamists take power. Some point to Iran's first post-revolutionary elections back in 1980 and Ayatollah Khomenei's promise that in the Islamic Republic the Majlis would not be a rubber-stamp parliament.

Ghannouchi scoffs at the idea that he is any Khomenei, but is clearly wary of being outflanked by more conservative Islamist trends. A week before the elections, a protest by Salafists against the Nessma TV station in Tunis that had broadcast an animated film they regarded as blasphemous ended in clashes with police. While condemning the violence, Ennahda said Nessma had "violated the fundamental right of all believers" in broadcasting the film.

Even so, many observers of the region say Tunisia has a better chance than most Arab states to forge a moderate Islamist democracy. A former French colony with close ties to Europe, it is the most industrialized of Arab countries, with an educated middle-class and newly thriving media. It is heavily reliant on tourism, and Ennahda has been quick to reassure the industry that alcohol and bikinis won't be outlawed. And whatever the transgressions of the Ben Ali regime that was overthrown in January, it was less mercurial and brutal than that of Gadhafi next door.

The danger for the emerging moderate Islamist parties is that they may fail. They have little experience of administration, having been driven underground by the previous regimes, and are prone to grand promises. Ennahda officials say they will create nearly 600,000 jobs by 2016 if they gain power, reducing Tunisia's unemployment, the issue of greatest concern to voters, from about 18 per cent to less than 10 per cent. That would be a tall order -- even if the economy were growing. This year, the International Monetary Fund expects the Tunisian economy to stand still, though it forecasts 3.9% growth next year.

Ennahda says it is inspired by the success of Turkey's Justice and Development Party in merging Islam and modernity. Justice and Development has now been in power for nearly a decade; it has won three elections and has presided over rapid economic growth (forecast at 8 per cent this year). It has also advanced the growth of an Islamic space in a country whose secular constitution is fiercely guarded by the military.

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a devout Muslim, made a triumphant tour of North Africa last month (all the more triumphant perhaps because of Turkey's recent falling-out with Israel) to tout the Turkish model. In Tunis, Erdogan predicted: "The success of the electoral process in Tunisia will show the world that democracy and Islam can go together."

To Erdogan, a person is not secular, but the state is. "This is not secularism in the Anglo-Saxon or Western sense," he told a news conference in Tunis. In Cairo, he told a television audience, "To Egyptians who view secularism as removing religion from the state, or as an infidel state, I say you are mistaken. It means respect to all religions." In other words: separation of religion and state.

This didn't go down well in Iran, where officials claimed Erdogan was trying to poison the minds of Muslims with secularism. And it wasn't very well received by the Muslim Brotherhood, which has emerged as a political force in post-Mubarak Egypt. A senior official of the Brotherhood said Erdogan's remarks amounted to interference in Egypt's affairs, while stressing the Brotherhood was committed to democracy.

Back home, critics say Erdogan is actually chipping away at the secular foundations of the Turkish state and is increasingly intolerant of critics. One example they cite: the recent prosecution of a cartoonist charged with "insulting the religious values of part of the population" with what some groups describe as blasphemous portrayal of a mosque. In addition, the state's long-running feud with Turkey's Kurdish minority shows no sign of abating.

But Turkey's economic power, pivotal geographic position and stability make it a major player in the region, all the more so as Arabs cast around for a new way of government. They have already rejected the authoritarian secularism of Mubarak and Ben Ali, its endemic corruption and nepotism, its stifling of opportunity. And there seems little popular enthusiasm (if rather limited polling is credible) for hard-line Salafist parties that demand strict adherence to Sharia as the source of legislation.

In some ways the experience of Islamist parties like Ennahda mirrors that of a majority of Arabs. They have emerged from a generation of repression, their traditional values marginalized by a domineering state. And they are ready for change.