Story highlights

The repeal of the "don't ask, don't tell" policy will become final on Tuesday

The law, barring gays from serving openly in the military, was enacted in 1993

Obama signed a bill repealing it in late 2010, setting off a transition process

An ex-Air Force sergeant outed by the policy says the military often doesn't like change

David Hall thought that he’d been careful, working diligently in his job as an Air Force sergeant, and staying quiet about his outside life, including his sexual orientation.

Then, a female cadet went to his commander, with the revelation that Hall – who had been first in his ROTC pilot’s training class and long aspired to a military career – was gay. Soon thereafter, in 2002, he was discharged, the life-long military brat’s dreams of being a pilot suddenly dashed.

“It was stunning, disappointing,” Hall said of being outed, and ousted, despite “doing everything that the Air Force had asked of me.” “I lost everything that I had been working for.”

But starting Tuesday, Hall’s future could take another turn. That’s when the U.S. Defense Department is set to formally repeal the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy that has been in place since 1993.

Advocates for the change overcame intense opposition from some who claimed allowing gay men and women to serve openly would hurt the military by making other troops uncomfortable and less effective, hurting morale and the military as a whole. And it also survived a last-minute push by two of the most powerful Republicans on the House Armed Service Committee to keep the policy in place.

“There were many times when we thought it wasn’t going to happen,” said Brian Moulton, chief legislative counsel for the Human Rights Campaign. “(Tuesday) is a tremendous day for (gay rights advocates).”

So, too, will be the days to follow. Hall, who joined the Air Force in 1996, said he’s already been in touch with a recruiter, as he’s actively considering returning to the military.

“My views of the military have never changed, I’ve always loved the military,” he said. “It is great (the law is no longer in effect), because it is going to make the military stronger.”

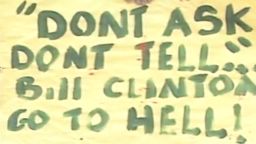

The policy, which became known as DADT, was extremely controversial when it first took shape. During his presidential campaign, Bill Clinton had vowed to let gays fight alongside straight people. But under intense pressure from conservatives fearful that such a policy would hurt the military’s effectiveness, the compromise was crafted.

Under it, military officials could not ask a soldier, sailor or airman about his or her sexual preferences. But if the troop’s orientation came to light, it could lead to their discharge from the military. Some, like Hall, claim they never brought anything up themselves to their superiors, but still were forced to leave.

Since its inception, the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network – which Hall now works for – estimates more than 14,000 people were kicked out of the military due to “don’t ask, don’t tell,” with the highest rates occurring in 2000 and 2001. The advocacy group said that its figures come from Defense Department statistics, obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests.

Efforts on Monday to reach several organizations that opposed the policy’s repeal were unsuccessful.

But those on the other side of the debate described DADT as discriminatory.

“This is one of two remaining federal laws where the government says, in point-blank terms: Gay people are treated one way, and straight people are treated another way,” said James Esseks, direction of the American Civil Liberty Union’s LGBT project, adding that the other law is the Defense of Marriage Act. “Discrimination is written right into the face of law.”

While serving, Hall said that it became “a game” for him and many other closeted military personnel, realizing “at work, I don’t talk about my personal life.” But in time, and after his discharge, the ex-Air Force sergeant said that he came to the realization that “the military was behind on this issue.”

“They don’t like change, and they don’t want change unless they have to do it,” he said.

Still, Clark Cooper, the executive director of the Log Cabin Republicans – a gay rights group, doesn’t expect the change to create major ripples.

“Sure there’s going to be some homophobia here and there, but at the end of the day, if you’re a service member, you are expected to be a professional,” he said. “Misbehavior won’t be tolerated and it won’t be allowed.”

Racial integration and the inclusion of women in the armed forces were bigger cultural steps, Cooper said.

By 2011, the militaries of several countries – including Israel and NATO allies like England, Germany and France – allowed gays to serve openly. And public opinion began to shift as well. In a Gallup poll from December 2010 – the same month a lame-duck Congress approved the repeal – 67% of respondents favored a similar policy in the United States, with 28% dissenting.

“Over the last 17 years, the country has learned a lot more about gay people,” said Esseks. “As a whole, it is much more comfortable with the fact that gay people exist.”

Even so, the effort led by President Barack Obama to repeal the law wasn’t without roadblocks. Sen. John McCain, an Arizona Republican and former war hero, was among those opposed, saying at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, “At this time, we should be inherently cautious about making any changes that would affect our military, and what changes we do make should be the product of careful and deliberate consideration.” Yet the Defense Department, despite reported dissent within its ranks, pushed for the change.

On December 22, 2010, Obama signed the repeal into law. But this didn’t set off an instantaneous change. Instead, the Pentagon rolled out a months-long process that would involve new training and rules, as well as a confirmation that it would not harm “military readiness.” Until that time, the policy officially remained in effect.

Last week, Rep. Buck McKeon, R-California, the chairman of the Armed Services Committee, and Rep. Joe Wilson, R-South Carolina, the chairman of the committee’s personnel subcommittee, hoped to keep it that way when they wrote Defense Secretary Leon Panetta asking him to “take immediate action to delay the implementation of repeal.” They claimed Congress has not been adequately informed of policy changes that will accompany the repeal.

A defense official who handles questions about the policy said that the department would not respond to a congressional letter via the media. But a spokesperson sent CNN a statement that read, in part, “The repeal of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ will occur, in accordance with the law and after a rigorous certification process, on September 20.”

The statement added that “senior Department of Defense officials have advised Congress of changes to regulations and policies associated with repeal” – including offering specific regulations and new policies in meetings with House Armed Services Committee staff.

Moulton, while claiming that gay, lesbian and transgender people still face “a great deal of legal and cultural discrimination,” nonetheless called the law’s formal repeal “a tipping point in the movement for equality.”

Esseks agreed, even as he predicted that the concept that people couldn’t fly planes, sail on Navy ships or fight in battle just because of their sexual orientation will seem antiquated in a few decades.

“There will be a lot of people who will look back and scratch their heads, and say why were people so worried?” he said. “It doesn’t mesh with their experience of America.”

CNN’s Larry Shaughnessy and John Fricke contributed to this report.