With more job openings than unemployed workers in the US economy, companies are finding it hard to fill jobs.

One solution is for corporations to train high school students with the skills needed in the labor market. Sometimes, they start as young as kindergarten.

Since 2011, more than 400 companies have partnered with 79 public high schools across the country to offer a six-year program called P-Tech. Students can enroll for grades 9 to 14 and earn both a high school and an associate's degree in a science, tech, engineering or math related field.

The companies offer input on the curriculum, bring students on site, pair them with employee mentors, and offer paid internships, or some combination of the above.

"There's a war for talent across all our competitors. We know we're going to need a lot of different pathways to bring talent in," said Jennifer Ryan Crozier, president of the IBM Foundation.

IBM was the first to try out the P-Tech model, working with a high school in Brooklyn and the City University of New York.

Since then, energy companies National Grid and Con Edison have partnered with another school in New York City, as has Montefiore Medical Center. Both Motorola and Verizon work with schools in Chicago and Dow Chemical will start working with a new program in Louisiana in the fall — to name a few.

Connecticut, Maryland, Rhode Island, Colorado, and Texas also have P-Tech schools, and state funding has been set aside to open some in California in 2019.

Related: There are now more job openings than workers to fill them

P-tech schools are a modern version of what were once commonly known as vocational schools. But unlike those of the past, which sometimes became a "dumping ground for less-academic kids," newer career and technical programs are careful not to close off a pathway to college, said Brian Jacob, a professor of education policy and economics at the University of Michigan.

Instead, they aim to prepare students for both a career and higher education.

In fact, a majority of P-Tech's early graduates have chosen to pursue a bachelor's degree rather than jump immediately into the workforce.

Employers know they are playing the long game.

"This is about preparing the next generation of the workforce," Crozier said. "It's not a short-term fix for roles we have open today," she said.

Many employers expect the skills gap to get worse if nothing is done.

"About five years ago, we took a look at the future gap in the workforce and decided that we need to do even more," said Ken Daly, COO at National Grid, which delivers energy to New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.

Not only is the industry's workforce aging, but there will be an increase in the number of new energy jobs created, he said. Plus, he doesn't believe today's students have as much of an interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) subjects as they did in the past. He's working to change that.

National Grid partnered with a P-Tech school in Queens in 2013. Its students visit National Grid's offices, one of its electric power plants, and a gas control center. Employees come to class to teach them how to fuse a gas pipe and splice a cable.

National Grid works with community colleges, middle schools and elementary schools, too. Daly recently visited a kindergarten class.

"We really believe that if we start young, we can create this pipeline of students who see a career in energy," he said.

Related: Discover will pay for its employees to earn a college degree

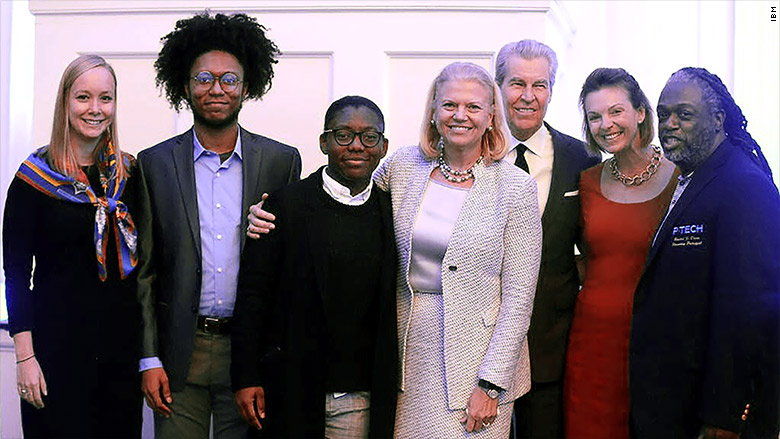

In 2016, Janiel Richards was one of the first to graduate from a P-Tech program. She earned an associate's degree in computer information systems and interned at IBM and CUNY during the summers.

Richards, now 20, was offered a job at IBM within two months of graduating. She currently works full-time there as a visual designer while also working toward a bachelor's degree in graphic communication at Baruch College in Manhattan.

"I really wanted to continue my education, but I also wanted to continue what I had going with IBM because I had such a strong network," Richards said.

P-Tech taught her coding and development, but she values the soft skills she learned there just as much. Good time management and open communication with her manager at work make it possible for her to handle the busy schedule.

"I've learned how to handle myself in the workplace, how to get my point across, and how to write an email to people like Ginni," she said, referencing IBM CEO Ginni Rometty.

It was her mom that encouraged her to enroll in P-Tech. Now that she has earned her associate's degree at no cost and launched her career at IBM, Richards helps support her mom and four younger sisters financially.