Angelo Mozilo got rich selling the American Dream. Then he became the face of America's mortgage nightmare.

Mozilo, the perpetually tanned son of a butcher from the Bronx, co-founded Countrywide Financial in 1969. He built it into an unstoppable mortgage machine that made it easy — evidently too easy — for millions to own a home.

Between 1982 and 2003, as home prices boomed and Countrywide's stock price zoomed 23,000%, Mozilo gained a reputation in the industry as a genius and a rainmaker.

He turned Countrywide into the No. 1 mortgage company. Between 1999 and 2006, he personally made more than $400 million, according to Equilar.

"He was the superstar," said James Rhodes, who joined Countrywide in 2005 to lead its packaging of commercial real estate loans into securities that could be sold to investors.

"We were leading the charge to make America great again, before that was even a thing," he said.

Yet Mozilo's quest to dominate the mortgage market led to a race to the bottom at Countrywide. The company repeatedly relaxed its borrowing standards, lending to people with weaker credit scores who sometimes didn't even have jobs.

Mozilo helped pioneer the use of subprime mortgages and other so-called exotic products. Hailed as brilliant at the time, these dangerous mortgages blew up when the unthinkable happened: Home prices collapsed.

"His actions suggest he was willing to push the system to its limit, irrespective of the consequences," said Dick Bove, a veteran banking industry analyst.

Related: The downfall of Bear Stearns and its bridge-playing CEO

Dangerous products

Under Mozilo, Countrywide pumped out complex mortgages to people who couldn't afford them — and often didn't understand them.

One product, an adjustable-rate mortgage known as a pay-option ARM, gave borrowers the option of making small payments in some months, or even skipping some payments altogether. Many borrowers ended up owing more than their houses were worth, resulting in countless foreclosures.

"The borrowers did not understand the risks involved with the mortgages. And Countrywide did not tell them," said Patricia McCoy, a professor at Boston College who studied Countrywide as part of a book she co-wrote called "The Subprime Virus."

Countrywide didn't worry much about what happened after the mortgage was signed because it packaged most of the loans together and shipped them off to Wall Street, a process known as securitization.

Countrywide sold or securitized 87% of the $1.5 trillion in mortgages it originated between 2002 and 2005, according to the final report by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, a bipartisan federal committee charged with investigating the causes of the meltdown.

"Ambition and arrogance made Countrywide offer to the market a product that was inferior," said Jonathan Adams, senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. "They did the market a terrible service."

'Old-fashioned bank run'

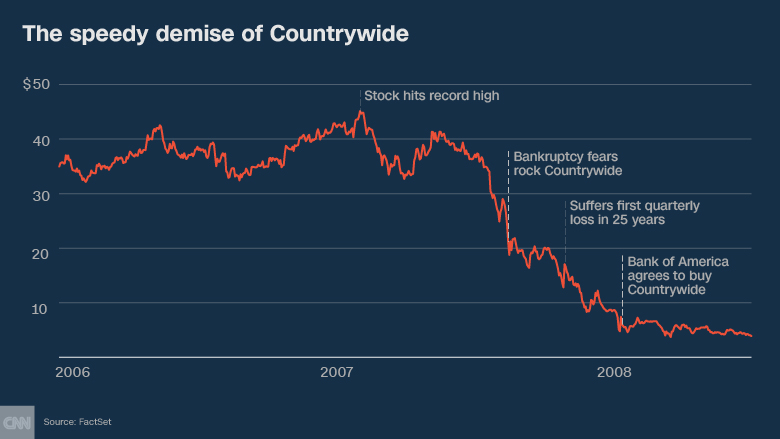

For years, countrywide's tactics worked spectacularly well. The stock hit a record as late as February 2007.

But cracks emerged as investors began to grasp the threat posed by toxic mortgages.

In April 2007, New Century, a rival subprime lender, filed for bankruptcy as the slumping housing market caused homeowner defaults to spike. Dozens of other lenders would follow.

But that August, Countrywide itself was fighting off bankruptcy fears as it reported rising foreclosures, declining loan production and job cuts.

Countrywide found itself unable to access short-term borrowing markets or to sell its mortgages to investors. Desperate for cash, Mozilo was forced to tap $11.5 billion of backup credit lines, a move that triggered a downgrade from the Moody's credit rating service.

Countrywide's stock plunged, customers started to yank their deposits from its banking arm, and trading partners backed away from the firm.

"The bad news led to an old-fashioned bank run," the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission concluded.

Countrywide reached a deal six days later to sell a 16% stake to Bank of America (BAC) for $2 billion. But the downturn in housing deepened, and the spiral for Countrywide accelerated.

In October, the company disclosed a stunning $1.2 billion loss — its first in 25 years — as loan losses surged.

Few believe Countrywide would have survived the coming storm had it not agreed in January 2008 to sell itself to Bank of America for $4 billion. That deal, approved by the Federal Reserve 10 years ago this week, went down as one of the worst a bank has ever made.

Later in 2008 came the collapse of IndyMac Bank, a California subprime lender that Mozilo and Countrywide had started in 1985 and later spun off as an independent company.

The bank became a poster child for risky home loans. The remains were acquired for pennies on the dollar by future Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

Related: 10 years after the crisis, have we learned anything?

Did Mozilo get off easy?

For his twin roles at Countrywide and IndyMac, two of the most notorious names of the crisis, Mozilo is remembered as one of the villains of 2008. Time magazine named him one of the 25 people to blame for the financial meltdown.

Yet, like other major figures in the crisis, Mozilo largely evaded tough penalties from the government.

For years, the Justice Department considered bringing criminal and civil charges against Mozilo. Neither brought a case.

"I look at Angelo as one who got off about as easy as anybody," said Nathan Stovall, senior research analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

In 2009, the SEC accused Mozilo of duping investors about how vulnerable Countrywide was to subprime mortgages — and then using inside information to dump $139 million of his own shares in 2006 and 2007 before they tanked.

While Mozilo was telling shareholders that Countrywide mostly lent to healthy borrowers, the SEC said, he was sounding the alarm inside the company with a "series of increasingly dire assessments" about the dangers ahead.

Specifically, Mozilo warned about the risks of 80/20 subprime loans, which allow borrowers with weak credit scores to buy a home without a down payment by taking out two loans, one for 80% of the value and a second for the remaining 20%.

"In all my years in the business," Mozilo told top lieutenants in an April 2006 email that was later published by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, "I have never seen a more toxic" product.

In a separate email that month, Mozilo said that he had "personally observed a serious lack of compliance" within Countrywide's process of documenting mortgages and a "deterioration in the quality of loans."

Mozilo also said that Countrywide was "flying blind" because it had "no way" to predict the performance of pay-option ARMs.

Related: My road back from the Great Recession

Shareholders 'run over'

To shareholders, Mozilo was hardly sounding the alarm.

At an industry conference just weeks later, in May 2006, Mozilo said Countrywide viewed the pay-option mortgages as a "sound investment." He repeatedly held up Countrywide as a safe lender that avoided the risky excesses of its peers.

Mozilo denied the SEC charges and agreed in October 2010 to pay $67.5 million to settle them. The SEC hailed it at the time as the largest penalty ever against a senior executive of a public company, but Bank of America paid two-thirds of the fine.

Mozilo wasn't targeted by Bank of America, despite the mountain of legal problems the bank inherited from Countrywide. Stovall estimates that Countrywide cost Bank of America and its shareholders at least $50 billion in legal bills, repurchases of faulty mortgages and other expenses.

"Bank of America shareholders got run over, not by a steamroller, but by another planet," Bove said. "Mozilo wasn't harmed at all."

Reached by phone in California, the 79-year-old Mozilo declined to speak. His lawyer did not respond to a request for comment. Bank of America declined to comment.

'A level of denial'

Even two years after Countrywide's collapse, Mozilo maintained that his company was an enormous force for good.

"Countrywide was one of the greatest companies in the history of this country and probably made more difference to society, to the integrity of our society, than any company in America in the history of America," he told federal investigators in 2010.

One former senior executive at Countrywide told CNNMoney that "Angelo really believed he was doing wonderful things for American housing."

But at least some Countrywide employees were more skeptical.

"I did not trust what was being told to me by my senior executives," the executive said. "There was a level of denial," the exec said.

Of course, Mozilo is hardly the only person deserving of blame for the mortgage debacle. Other subprime lenders such as New Century Financial, Ameriquest and American Home Mortgage either failed or were acquired in fire sales.

Countless Americans tried to get in on the gold rush of soaring home prices by flipping homes. Congress ignored the warning signs and continued to push homeownership. And credit rating companies, eager to maintain the flow of lucrative fees, blessed risky mortgage securities that would later implode.

"Almost all interests were aligned to keep housing moving up," Stovall said.

Related: Millennials born in 1980s may never recover from Great Recession

The 'wild west' of regulation

Regulators failed to aggressively police the mortgage industry, allowing fraud and dangerous loan products to fester for years.

"It was the wild west," Stovall said.

Worse, Countrywide was allowed to shop around for more lenient regulators who wouldn't ask as many questions.

In December 2006, Countrywide applied to become a thrift, allowing it to move under the oversight of the Treasury Department's Office of Thrift Supervision. The OTS, known as the weakest cop on the beat, oversaw three of the most infamous companies of the 2008 crisis: AIG (AIG), Washington Mutual and IndyMac.

"The OTS pandered to the industry" to the point of "near corruption," said McCoy, the Boston College professor and author, who is also a former mortgage regulator at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Under the Dodd-Frank law of 2010, Congress abolished the OTS. The legislation created the CFPB, which sniffs out mortgage and other types of abuse.

Since taking office last year, President Trump has signed laws that have chipped away at post-crisis regulations. Trump has also handpicked leaders for regulatory agencies who support rolling back rules. Mick Mulvaney, the acting head of the CFPB, once called the agency a "joke" and pushed to eliminate it.

Although the vast majority of Dodd-Frank remains intact, the deregulatory shift in America has raised concern that the lessons of Countrywide have already been forgotten.

"We need to be very cautious," Adams said. "It would be a mistake to bring ourselves anywhere close to where we were just prior to the financial crisis."