When the e-scooter company Matt Gialich used to work for had to pause production owing to a shortage of platinum, a key component for the microprocessor that translates commands from the controls to the motor, he went down a rabbit hole researching metals.

Gialich, whose childhood love of space led him into engineering and a job at the satellite launch company Virgin Orbit before its bankruptcy, began wondering how to extract the metal in asteroids. Scientists believe these chunks of celestial debris, which are by-products from the birth of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago, are rich in metals that are in short supply on Earth.

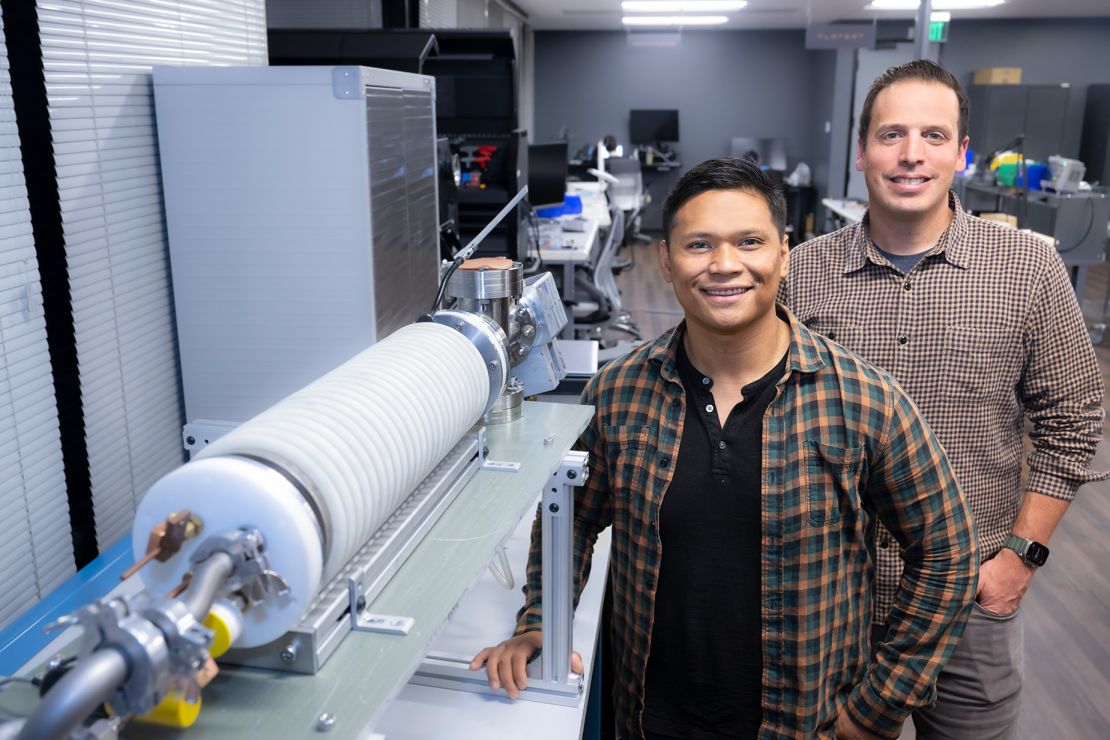

In 2022, Gialich and Jose Acain, who has almost a decade of experience at SpaceX and NASA, founded AstroForge. Now the California-based startup is attempting to make asteroid mining a reality.

The company isn’t alone. The clean energy transition is expected to cause demand for mineral resources to soar, and interest in extracting them from previously untapped sources, like the ocean floor and space, is growing. Companies across the world have raised tens of millions of dollars to test asteroid-mining technologies.

Some say the idea is a prohibitively expensive, far-fetched fantasy. But 38-year-old Gialich thinks it could be put into practice soon. “Going out and securing resources from space is this Holy Grail,” he says. “I think we’re finally at this inflection point where we can take it on.”

A moonshot idea?

Gialich has no problem admitting that his company’s plans are ambitious. “We’re going to have a lot of failures,” he says.

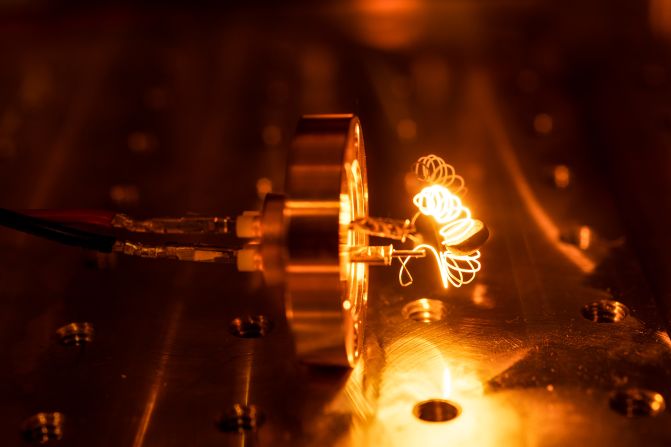

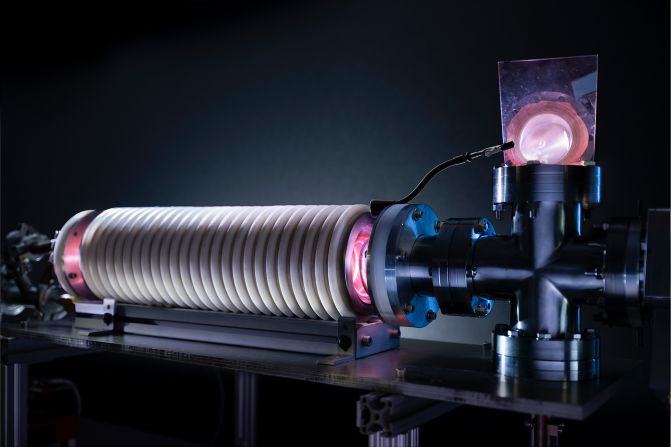

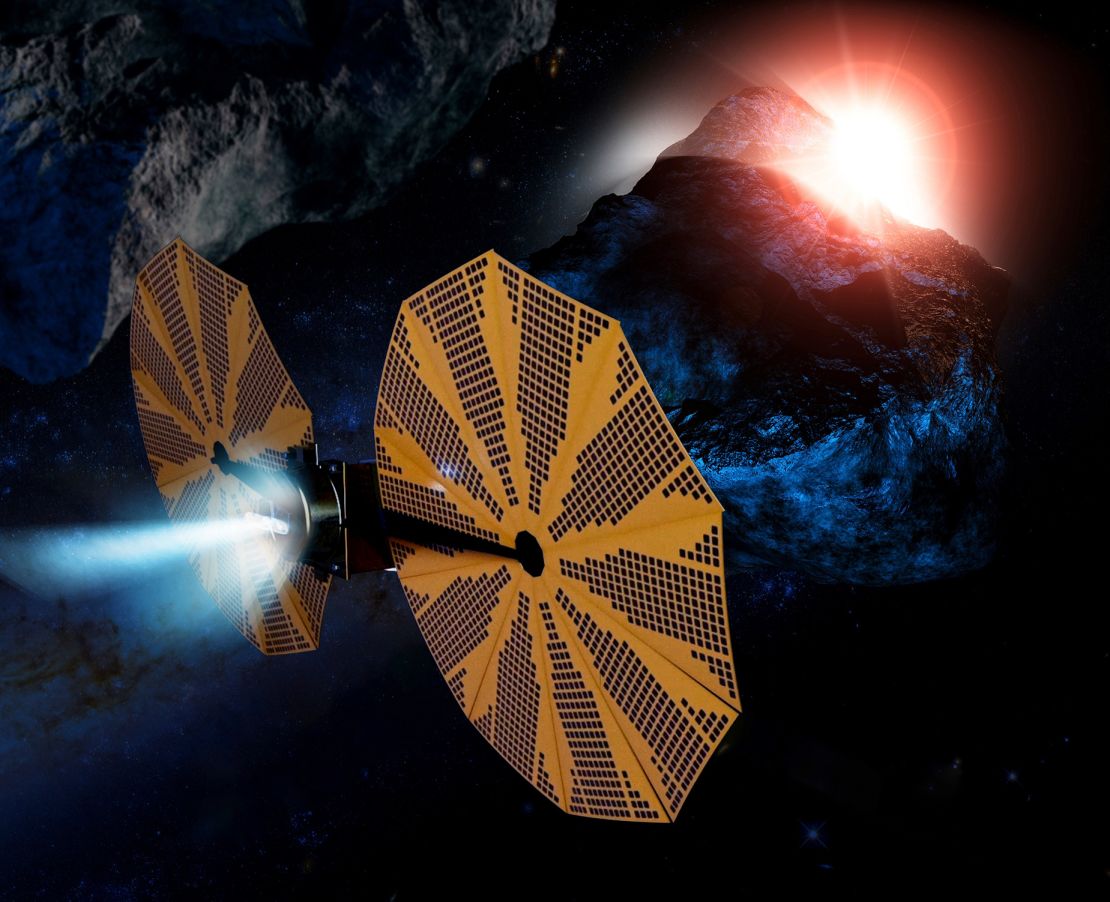

AstroForge is, in short, attempting to send into space a tiny refinery that can extract minerals out of an asteroid, then bring the valuable metals back to Earth, leaving the rest. The company is targeting M-type, or metallic, asteroids for platinum group metals (PGMs), which are used in everything from jewelry to catalytic converters that filter car exhaust to cancer-fighting drugs.

PGMs like platinum and iridium are also critical raw materials for emerging clean energy technologies. Green hydrogen production, for example, is expected to drive major growth in demand for the minerals. But earthly supplies are limited and geographically concentrated.

Although it sounds like a plot straight from the latest season of the Apple TV+ show “For All Mankind,” which involved an elaborate plan to harness an asteroid and bring it into Earth’s orbit for mining, Gialich says “that’s not what we’re doing at all.”

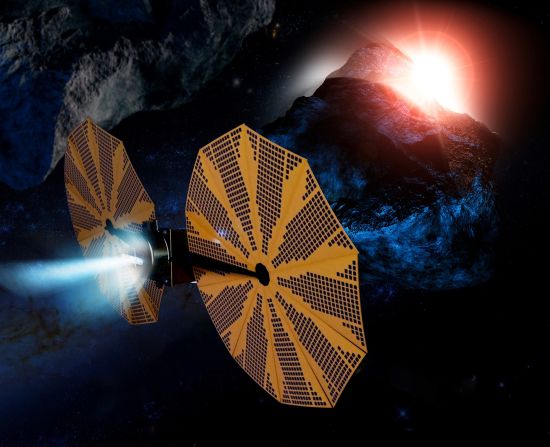

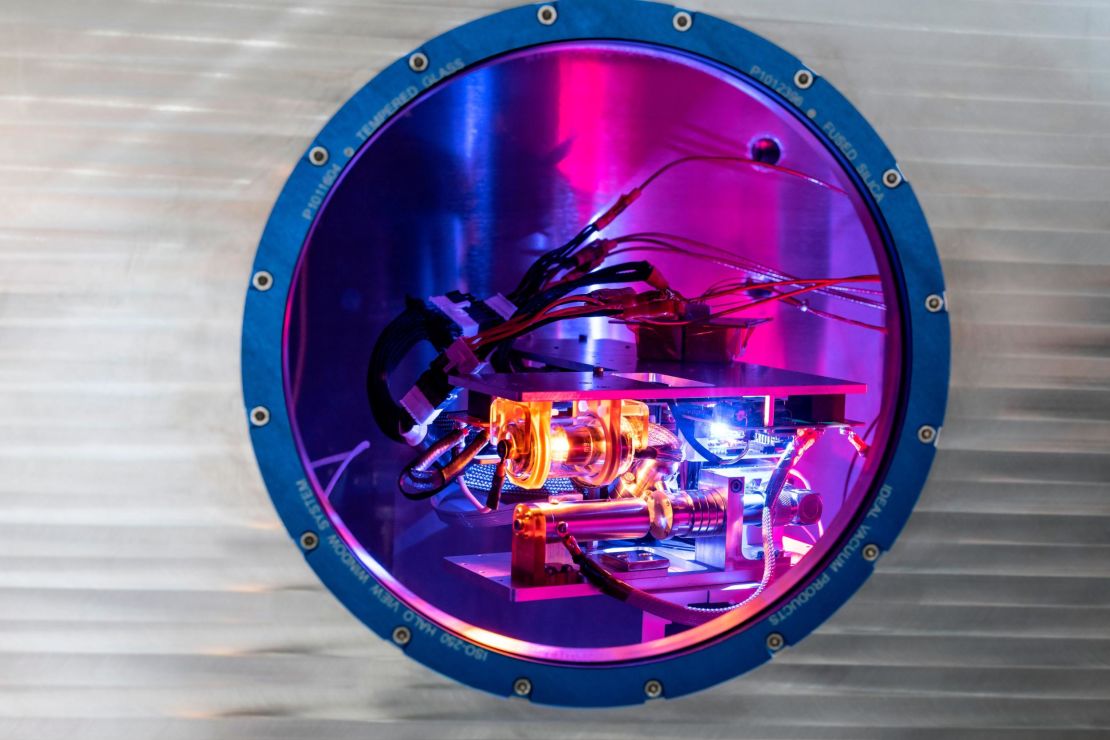

Last April, AstroForge launched its inaugural mission, called Brokkr-1, sending a miniature satellite equipped with a refinery system about the size of two loaves of bread into space. The spacecraft carried pre-loaded, asteroid-like material it planned to vaporize and sort into elemental components while in orbit.

It hasn’t gone quite as planned, and the refinery demonstration hasn’t happened yet. But Gialich says the company learned a lot, like how any equipment sourced from vendors would perform, and if the machine could survive blastoff and send signals back from space.

The refinery – which AstroForge has patents on – has already been tested terrestrially in space-like conditions, he says. That makes AstroForge the only company with a refinery that can turn M-type asteroids into PGMs in space, he adds.

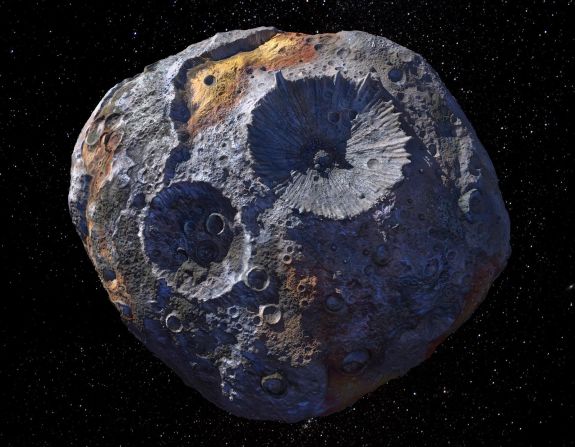

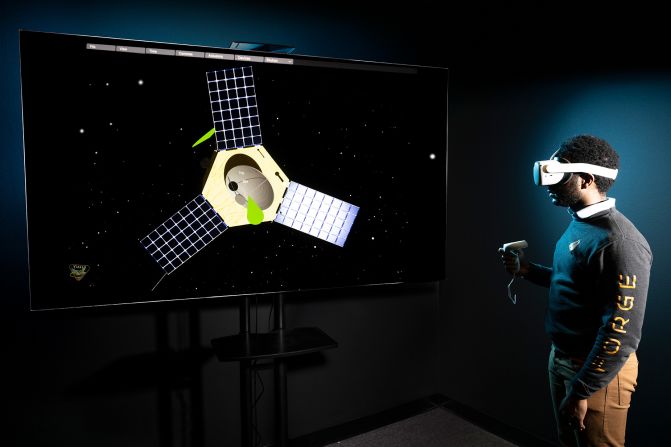

This year, an AstroForge spacecraft will hitch a ride on a mission by US-space exploration company Intuitive Machines to the Moon. But AstroForge will jump ship and use its own propulsion system to fly by an asteroid it thinks is metallic to check out its composition and take pictures. (Gialich declined to specify which asteroid the company is targeting.) If this mission succeeds, it will make AstroForge the first commercial company to venture into deep space, it says. It could also provide the first high resolution images of a metallic asteroid.

‘High-risk, high-reward’

Interest in asteroids – both for better understanding Earth’s origins and their composition, which could lay the groundwork for miners – is skyrocketing, and experts say asteroid mining may just be a matter of time.

Dan Britt, the director of the Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science at the University of Central Florida, who is not directly involved with AstroForge, ponders: “I suppose you could ask whether [humans] are totally crazy to do this. The answer is, it might be a bit early, but we’re not totally crazy.”

The likes of JAXA, Japan’s space agency, and NASA have already brought asteroid samples back to Earth, proving, at least to an extent, that it can be done.

China plans to launch a mission in 2025 to collect samples from a near-Earth asteroid, while the United Arab Emirates’ Space Agency is planning to explore the asteroid belt with a mission scheduled to launch in 2028.

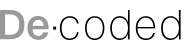

NASA has a spacecraft en route to asteroid Psyche, which is orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter, but it won’t get there until 2029. By some estimates, the iron in the 140-mile-wide metal-rich asteroid is worth $10,000 quadrillion – more than the value of the entire global economy. (Gialich says that NASA scientists have been excellent allies, providing invaluable expertise to AstroForge.)

Some in the scientific community are skeptical that the private sector will be able to afford asteroid mining. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission, the first US mission to collect an asteroid sample and bring it back to Earth, cost hundreds of millions of dollars, excluding launch cost. Its return of just 122 grams, which landed in a Utah desert last year, is the largest asteroid sample ever collected.

“This actually is not a question of if it can be done from a physics standpoint,” says Gialich. “It’s a question of can you do it so it makes any monetary sense.”

Others have tried and failed. Planetary Resources, for example, launched in 2012 with the backing of high-profile investors including “Titanic” director James Cameron and Google co-founder Larry Page. By 2020, it was holding an online fire sale after facing funding difficulties and being acquired by a blockchain firm. (Buyers in the Internet auction scored items like a plastic tub full of assorted, tangled electrical cords for $10 and a pair of well-used insulated gloves for $20.)

A lot has also changed. Private companies like SpaceX have dramatically decreased the cost of space travel. Gialich says today more is known about the solar system’s 1.3 million asteroids, so companies like his don’t have to waste resources looking for them, and that AstroForge has invested in developing algorithms that allow it to rideshare and get where it’s trying to go.

“Lower transportation costs are key to developing an off-world economy,” says Britt, who has contributed to four NASA missions, including a flyby of an asteroid in the Kuiper Belt, a donut-shaped ring of debris at the edge of the solar system, and a series of journeys to asteroids near Jupiter, and has an asteroid named after him for his contributions to asteroid research.

The changes have driven a wave of new interest. Other companies, like Los Angeles-headquartered TransAstra and China-based Origin Space, are working on technologies that can mine resources in space.

So far, AstroForge has raised $13 million in seed funding. It says its second mission will cost less than $10 million, which means the company will be putting most of its eggs in one basket. “These are high-risk, high-reward ventures, to be very clear,” says Gialich.

He doesn’t yet have a plan B if the planned missions aren’t successful. “Who cares? You go out and you try these big missions, these big gambles, and if it doesn’t work, I don’t know. I guess I go get a job somewhere?” he says. “I’m just focused on plan A and trying to make that happen.”

Supplies from the skies

If all goes well, the company’s eventual aim is to bring back about 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of PGMs per mission, a payload which could be worth around $70 million, depending on the metals and their price at the time. “Even with multiple hiccups in our schedule, we are attempting to mine an asteroid and we’ll have brought it back before the end of this decade,” Gialich says.

Because the company is targeting relatively smaller asteroids, it says there will be less gravity to overcome, and therefore less fuel to burn.

Its all-or-nothing, lower-cost approach may help push asteroid mining closer to reality.

“Even if we’re not successful and we fail as a company, I hope that we push this forward a little bit,” he says, and demonstrate that “you can do a lot more science with a lot less capital.”

Britt says asteroid mining is likely to “happen eventually” and the technology in the market is already a lot more advanced than “a soggy bar napkin with a bunch of equations and diagrams drawn on it.”

But he expects that technologies will need to advance even further before investors are willing to put big chunks of capital behind it.

“That’s one of the things that startups like AstroForge are doing – creating that new technology and engineering,” Britt says.

It may be years before we know if AstroForge’s attempts have a lasting impact on the wider push to extract minerals from space. But its moonshot approach is likely to be remembered. “I hope if nothing else,” Gialich says, “we’re known as a space company that went for it.”