Even for locals, travel inside the isolated nation officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is heavily restricted.

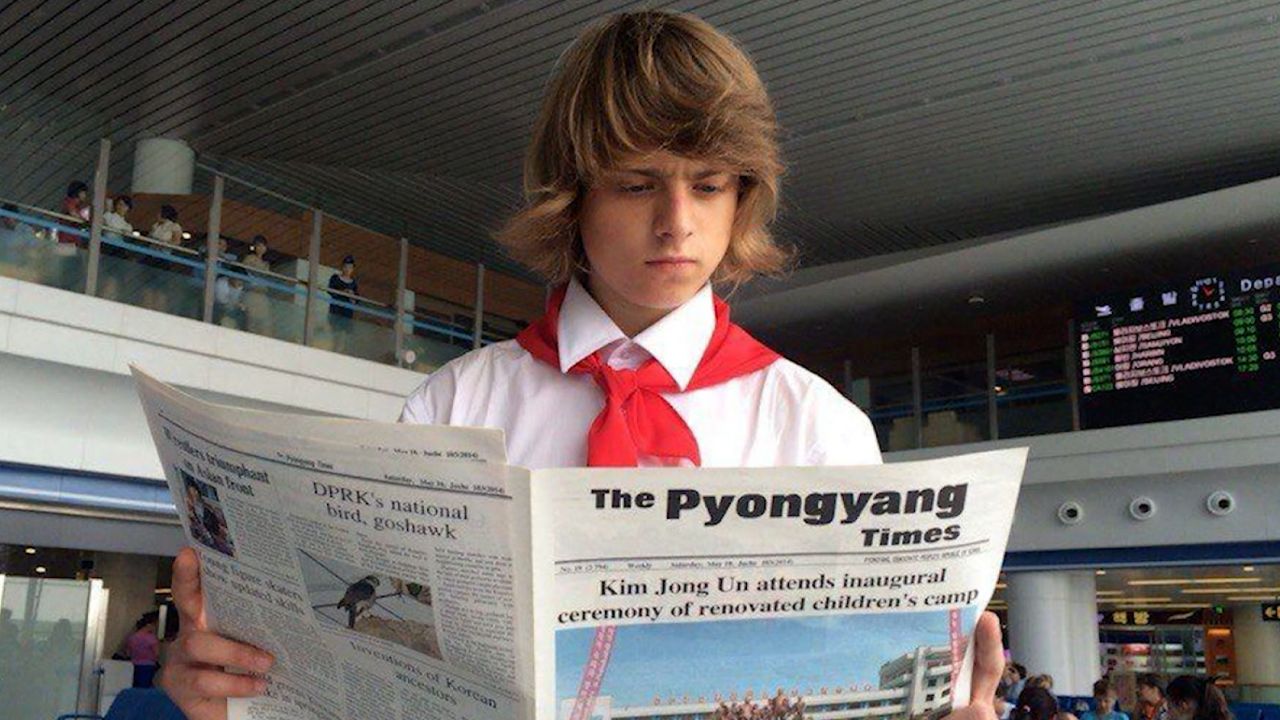

But arranging a trip was much easier for Russian national Yuri Frolov, 25, who spent two weeks in the hermit kingdom as a high-school student in 2015 and 2016. Yuri’s fascination with North Korea began with a TV documentary that portrayed the country as besieged by capitalist neighbors. This curiosity led him to join a “Solidarity with North Korea” group on VKontakte, Russia’s Facebook equivalent.

Through this group, he found an opportunity to attend Songdowon International Children’s Camp in Wonsan, on North Korea’s east coast. About $500 covered all expenses for a 15-day trip. His parents consented, and he traveled alone from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok, joining other children and Communist Party officials on the journey.

Earlier this year, 100 Russian nationals were the first tour group allowed to visit North Korea since the pandemic, a sign of Russia’s increasing popularity as Pyongyang deepens ties with Moscow. Before the pandemic, the largest source of inbound tourists to North Korea wasn’t Russia – it was China.

Upon his arrival at Songdowon International Children’s Camp in summer 2015, the camp staff greeted Frolov and his group warmly. The camp hosted children from various countries, including Laos, Nigeria, Tanzania and China. However, interactions with North Korean kids were limited to the final day, a deliberate move to prevent any exchange of real experiences.

The camp offered typical summer activities like beach outings and sandcastle-building competitions but also included peculiar rituals. Campers were required to wake at 6 a.m. and clean statues of former North Korean leaders Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, even though professionals already maintained the monuments.

Having reported from North Korea 19 times, I find Frolov’s experiences both relatable and eye-opening. The heavy emphasis on propaganda, the strict supervision, and the bizarre mix of freedom and control are aspects I’ve encountered repeatedly.

One of the more bizarre activities at the summer camp involved a computer game where players, as a hamster in a tank, had to destroy the White House.

This game reminded me of an exchange I had with two North Korean campers playing a similar game. When I asked who they were shooting, they responded, “Our sworn enemy, Americans.” I then asked, “What if I told you I’m an American? Do you want to shoot me too?” Without hesitation, they replied, “Yes.” After reassuring the youngsters I was a “good American,” they decided I should be allowed to live. And then they smiled and waved as we said goodbye.

This is the paradox of North Korea. People were usually friendly and polite, even as they told me the United States should “drown in a sea of fire.”

Despite the heavy propaganda, Frolov remained skeptical. The strict schedule frustrated him, especially when he wasn’t allowed to skip early-morning exercise despite being sick. The camp’s food was another challenge, with Frolov saying he mostly subsisted on rice, potato wedges and bread, leading to an 11-pound weight loss over the 15 days. His craving for familiar food was so intense that upon returning home, he bought a feast from Burger King, though he couldn’t finish it all.

Frolov recounted a memorable incident in Pyongyang: “There was a girl, very young, wearing a dress styled like the American flag in the city center. Surprisingly, no one was angry with her, even though she was told not to wear it again. It was a bizarre moment in such a controlled environment.”

“Many things seemed fake, especially the science and innovation buildings. They were not convincing, even for a kid,” he reflected. “It wasn’t a totally awful experience. I was mostly just bored. Apart from the lack of internet, it felt like any basic Russian camp for children.”

Despite the unpleasant and tightly controlled environment, he opted to return to the camp the following year, partly due to the Communist Party’s arrangements and what he describes as his aversion to confrontation.

In hindsight, Frolov acknowledges the decision as foolish but appreciates the unique stories he can share about North Korea.

His account offers a rare glimpse into the experiences of foreign children at a North Korean summer camp, highlighting the country’s efforts to indoctrinate young minds through a mix of cultural exchange and propaganda.

Yuri Frolov’s story is a powerful reminder of the lengths to which North Korea will go to shape perceptions and cultivate loyalty. His experiences at Songdowon International Children’s Camp highlight the regime’s use of propaganda and control to influence young minds, a strategy I’ve observed firsthand during my reporting trips.

Despite the stark differences in our roles – him as a camper and me as a journalist – our experiences reveal the same underlying truth about North Korea’s relentless pursuit of ideological control.