On a September morning in 1830, a throng of people gathered in the English cities of Liverpool and Manchester to see a daring feat of modernity.

Nobles, tipsy workers and politicians watched the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first railroad on Earth whose cars would be unaided by teams of horses.

Almost 100 years later, a 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight between North America and the European mainland, where he descended from his monoplane into crowds of Parisians chanting “Vive l’Americain!”

It was 1927, and after a century of new technologies, war and newly globalized mass commerce, travel had been transformed.

That period between those two extraordinary feats is the focus of Marc Walter and Sabine Arqué’s new book for publishing house Taschen, “The Grand Tour: The Golden Age of Travel.”

Arqué’s writing accompanies reproductions from Walter’s extensive collection of vintage travel images.

Symbols of a changing world

“In the course of 100 years both the conditions and the very concept of travel were progressively and permanently transformed,” Arqué writes.

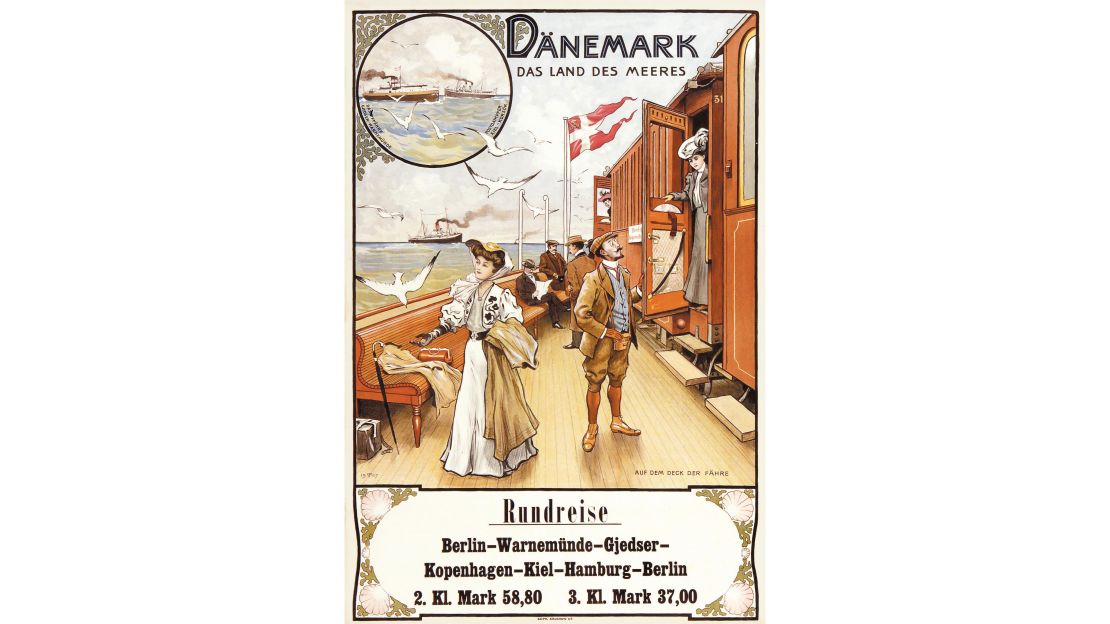

For the modern traveler, the book’s collection of postcards, photographs and ephemera is full of dreamy nostalgia of romantic destinations.

Vintage postcards show New York streets in rosy hues, and stylish posters advertise elegant cruise liners. Crystal sparkles in dining rooms aboard the Orient Express, while travelers in period attire scale the pyramids or summit Mount Vesuvius.

According to Arqué, however, contemporary travelers would have seen those images as emblems of a changing world.

“Today it appears quite romantic and old fashioned,” says Arqué, speaking from her Paris studio, “but the photochroms of the period focused on what was modern at the time – the railways, the cart railways, the first cars, all these inventions.”

A Century of technology

Between 1830 and 1930, the world saw an energetic burst of technological innovation.

In 1900, three years before the Wright brothers took to the air at Kitty Hawk, the airship Zeppelin LZ1 lifted off above Lake Constance, Germany, making the fantastical-seeming possibility of air travel a reality.

A 1905 postcard in “The Grand Tour” depicts Germany’s pre-war prowess, and the meeting of two now-bygone technologies: a Zeppelin floats above the historic center of a lake-front village, while smoke pours from a coal-powered boat in the foreground.

After the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened to the public in 1830, a frenzy of rail lines blazed across the Siberian tundra, through the mountains of the American West and to the stylish resorts of the French Riviera.

Though mass travel opened the world to some members of the middle class, many voyages combined cutting-edge speed with opulence only the rich could afford. The 1883 Orient Express, linking Paris with Constantinople (now Istanbul), turned a grueling voyage across Europe into an opulent lark.

In one of the book’s black and white photographs, the Orient Express’ dining tables are decked with crisp linens and carnations, while a hand-written dinner menu from 1884 evokes a feast that starts with perles du Japon, or tapioca, and concludes with a rich chocolate cream.

Inlaid wood gleamed inside luxury travel compartments, which also featured central heat and hot water, more than half a century before most American homes enjoyed the same amenities.

Ocean liners competing to be faster

As trains sped across six continents, ocean liners competed for the prestigious Blue Riband, a trophy awarded for the fastest transatlantic crossing.

In 1838, the SS Great Western, then the largest passenger ship in the world, made the trip from Bristol to New York in nearly 15 days, beating the previous record of 18 days that had been set by the SS Sirius just the day before.

By the end of Walter and Arqué’s “Golden Age,” the crossing had been shaved to four days and 17 hours. Long before the cutting-edge RMS Titanic sunk in the North Atlantic, ships strove for ever-swifter crossings, sometimes traveling at speeds that endangered passengers’ comfort and safety.

“The major winners of the Blue Riband,” Arqué writes, “took great risks to carry off the prize, which brought valuable publicity.”

Each record-breaking crossing was feat of daring and technology, but images in the book show the ship’s elegant passenger quarters.

A series of photographs depict the opulence of the SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie, where the first-class dining room soars to a stained glass ceiling, and a domed smoking room is lined with Ionic columns and plush chairs.

Not that luxury accommodations were the norm. Arqué notes that despite the ostentatious images that appeared on the advertisements of the time, transporting the working class was an even more profitable business.

She writes that “the shipping companies… made their profits by cramming third-class passengers – in other words, immigrants –into the hold,” where conditions could be grim.

A glimpse of the exotic

As travelers sped to each corner of the globe, the popularization of photography changed the way they remembered their trips.

“Photography became commercial because travelers didn’t have cameras,” says Marc Walter. “So there was a business of photography that started in the 1860s and 70s.”

“The photographers would install themselves in very touristy places, like Venice or later Jerusalem, and they sold series of prints, photographic prints and albums. Tourists would order an album of their trip, or they’d buy photographs while traveling and put them into an album back at home.”

In “The Grand Tour,” images from Walter’s collection gathered over more than 40 years include portraits of tourists taken by photographers who would set up shop at each destination.

On the summit of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius, gowned Victorian-era tourists pose with parasols, as one is carried in a litter by four men. Straight-backed travelers in elegant hats sit atop camels and donkeys before the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.

These were not the first swaggering vacation images to be brought home as prizes – the aristocratic travelers of the 18th-century paid artists to create painted portraits of them with the backdrop of Greek and Roman ruins – but they’re a dramatic departure from the classic style of those earlier canvases.

And though many of these photographs were for wealthy patrons, postcards and photographs also became a first glimpse of the wider world for many others.

“In New York there were many agencies that sold views of America, views of Europe and collections of art,” Walter says. “It was an invitation to travel, but the people who bought these reproductions hadn’t necessarily traveled.”

After a Swiss inventor created the photochrom process for creating color photographs, the technology quickly traveled to the United States.

“When the Swiss had the idea to implement the idea in the USA,” he explains, “it was also the idea to photograph all the great American landscapes so that people could buy them who didn’t have the opportunity to travel.”

It touched off a craze. After the US Congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act in 1898, Americans jumped at the chance to send each other postcards similar to those in “The Grand Tour.”

“They had the most touristy places, like the Grand Canyon and Niagara-the ‘unavoidable’ places – but there was also a more documentarian approach,” says Walter. “The postcards were gathered into little booklets and even distributed in schools in the United States.”

Classic journeys

In “The Grand Tour,” six chapters evoke journeys to six regions of the world, from the northern route across Europe to the long and adventurous passage to Australia.

With the Instagram-like hues of the early photochroms, they’re often a reminder that today’s travelers are drawn to some of the very same places that enchanted their 19th-century predecessors.

The sheer rock faces of Half Dome and El Capitan have a warm cast in early images of Yosemite. Tourists feed pigeons on St. Mark’s Square in Venice, and smiling couples pose at the base of the Parthenon’s massive columns.

Others, though, show a world that’s been transformed by more than changing technology.

In images from Africa, travelers garbed in white suits and dresses are carried in litters and rickshaws at a time when much of the continent was still squeezed by colonial rule.

Elegant hotels opened in Aleppo, once said to be among the world’s most beautiful cities, while visitors to the Syrian capital of Damascus strolled gracious gardens and squares along the Barada River.

And like some of the places depicted in early photochroms, travel has been forever changed by time.

A trip on Route 66

Route 66 was completed in 1926, a ribbon of pavement across the United States that signaled the coming age of road trips. Just over 20 years later, Jack Kerouac set out on a series of jaunts that inspired “On the Road,” a book that would define free-spirited adventurous travel for generations to come.

“Somewhere along the line I knew there’d girls, visions, everything,” wrote Kerouac, “somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me.”

In the introduction to “The Grand Tour,” Arqué quotes Kerouac’s words alongside the French writer Alexandre Dumas, highlighting the sparkling independence they both found in a long journey, even while writing more than a century apart.

“To travel is to live in all the meaning of the word,” wrote Dumas, “to breathe the free air, feel the joy of living, to become an integral part of creation.”

It’s a message that Arqué invites readers to take to heart. “The golden age of travel is over,” she writes, “but the spirit of travel lives on.”