A star-shaped fortress atop a picturesque island off the southwest coast of Ireland once housed one of the world’s biggest prison populations.

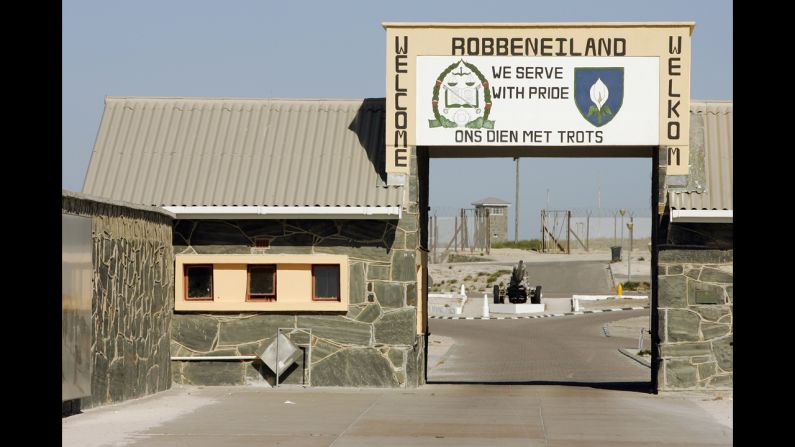

While Spike Island was welcoming boatloads of tourists pre-pandemic – much like Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay or Robben Island off the coast of South Africa – in Victorian times it was a place that many never left, with more than 1,000 prisoners dying there in less than four years.

In an attempt to learn more about the men who perished on this prison island, bioarchaeologist Barra O’Donnabhain began excavating the convict graveyard in 2013.

Over the past seven years, O’Donnabhain and his team have uncovered some of the mysteries buried on Spike Island – including a grizzly procedure long ago carried out on dead prisoners’ corpses.

In August 2020, island manager John Crotty announced one of the biggest discoveries yet: a secret stone spiral staircase dating back to the end of the 18th century.

How an island became a prison

Spike Island – often described as “Ireland’s Alcatraz” – has a multilayered history.

Early records indicate the 104-acre island might have been a 6th-century monastic settlement. It gradually developed into a British military base in the 18th century, before it became a depot for convicts waiting to be shipped to Britain’s penal colonies, such as Australia and Bermuda.

The original 10-acre British fortress was built in the late 1700s, but was considered too small to protect the Empire from potential invasion by Napoleon’s forces, so a second, much larger, 24-acre fort was built in 1804.

Excavation work on a tunnel leading from the inner fortress to the outer moat recently revealed a secret spiral stone staircase, which was not recorded on any of the island’s plans.

Large animal bones and half-drunk bottle of wines were found at the foot of the stairs. “The 1804 plans and later drawings make no reference to the staircase, so it truly was a most pleasant shock to see this door leading off this chamber of secrets to such a beautiful piece of stonework,” Crotty said in a press release,

Spike Island’s assistant manager, Alan O’Callaghan, tells CNN of the excitement around the discovery. “It also leads to the possibility that there are other types of these staircases in other parts of the older fort. It may have been used for other purposes over the years, for escape attempts and so forth.”

“The prison was opened as a crisis response by the government to the Great Famine and to the perceived rise in criminality, because the court system at the time punished theft very harshly,” O’Donnabhain, an archaeology professor at University College Cork in Ireland, told CNN in 2018.

From 1847, men and boys as young as 12 were sent to Spike Island, some for crimes that would today be considered trivial offenses, such as stealing potatoes.

‘Hell on Earth’

But by 1853 the number of prisoners on the island had risen to 2,500, making it possibly the biggest prison in the British Empire at the time, if not the world, in terms of the number of prisoners, according to O’Donnabhain.

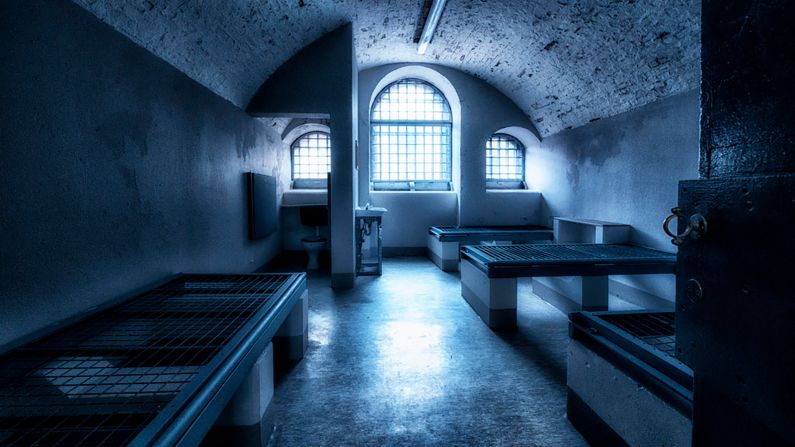

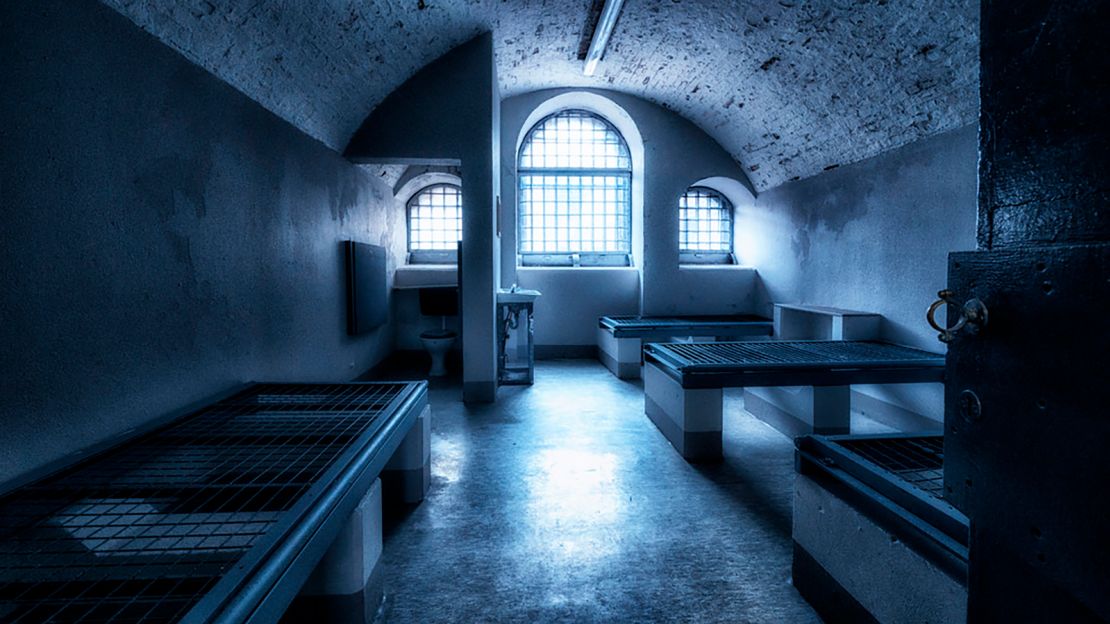

Up to 40 prisoners were sardined in each dormitory-style room – measuring 40 feet by 18 feet – and there were no individual cells save for the punishment block, used to detain the most dangerous criminals.

Various convict accounts from the punishment block detail how prisoners were heavily chained from wrist to ankle and severely broken from enduring what they described as “Hell on Earth.”

The prison’s draconian regime of forced labor coupled with poor living conditions and an inadequate diet meant convicts died almost daily in the early years, explains O’Donnabhain.

Digging up Spike

Records indicate that one of the island’s two graveyards holds upwards of 1,000 prisoners who died before 1860.

O’Donnabhain told CNN in 2018 that he and his team had so far excavated 35 burials from the other graveyard, which was used from 1860 onwards. By this point the number of deaths had drastically reduced to approximately one per month.

He says he was surprised by the element of care employed when prisoners buried their fellow inmates, particularly by how carefully they painted the cheap pine coffins to look like oak coffins.

“I read it as a gift from one prisoner to another,” says O’Donnabhain. “You’re being buried in a convict graveyard on a convict island that’s out of bounds to the rest of society, and yet your peers are just taking care to make a statement that this person was of some worth.”

Skulls for ‘science’?

But one of the most curious discoveries was that a handful of skeletons had the top of their skulls removed.

O’Donnabhain speculates that this might have been part of a wider study in the 1870s spearheaded by Italian scientist Cesare Lombroso to identify the characteristic physical features of the “born criminal.”

“Lombroso did a lot of autopsies of hanged criminals, and he found a particular variation in the architecture of the skull which he said is the sign of the ‘natural born criminal,’” explains O’Donnabhain.

Unsurprisingly, Lombroso’s theories have long been discredited.

But O’Donnabhain says he can’t be certain that that’s exactly what they were doing on Spike Island.

Writing’s on the wall

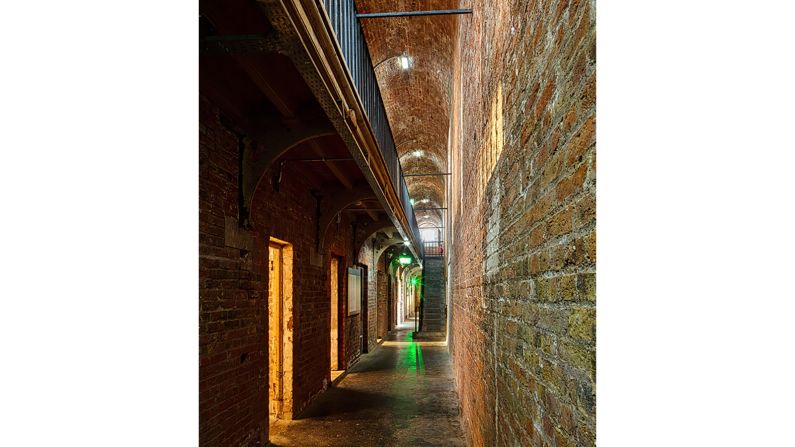

When the 19th-century prison closed in 1883, the island resumed its original function as a military barracks, only to re-open as a prison from 1985 to 2004.

When O’Donnabhain arrived nearly a decade later he says the sheets were literally still on the beds.

So, before he began excavating, his team documented the modern graffiti scrawled by 20th century prisoners.

“What really struck me in doing that work was the continuity between the Victorian prison and the modern prison,” says O’Donnabhain.

The graffiti on the walls detailed the prisoners’ nicknames, sentences, and hometowns. O’Donnabhain says these modern prisoners came from the same “blackspots of social disadvantage” as prisoners during the Victorian era.

“You see exactly the same dynamic in the sense that it’s primarily the poor who end up in prison and its people from socially disadvantaged backgrounds,” he says.

Spike Island first opened to the public in 2016 and was named “Europe’s Leading Tourist Attraction” at the World Travel Awards in 2017.

O’Donnabhain says tourists are curious to explore the island because of its dark past.

“People are drawn to places that are out of bounds,” he says. “If you tell people they can’t go there, they want to see what’s behind the walls.”