Two decades ago more than 40 million people flocked to see some amazing structures on the outskirts of Seville, Spain. Today, the amazing structures are still there, but almost no one visits.

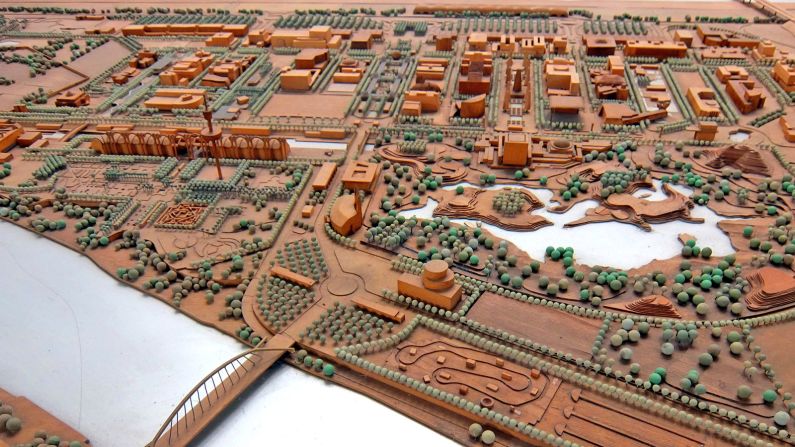

Created by some of the world’s leading architects, the buildings were commissioned for the Universal Exposition of Seville (or Expo 92, as it became known) to celebrate the modern age and offer blueprints for the future.

They were supposed to be temporary, scheduled for demolition in the months that followed the Expo. That didn’t happen.

Today many of the buildings still stand as beautiful and sometimes bizarre snapshots of a golden era of recent architectural and political history, making for an unusual destination.

Now incorporated into a science and education park, they’re also a symbol of hope for a country struggling to get back on its feet after near economic collapse. (Or as some in Seville see it: expensive relics of an event that left the city saddled with debts for many years.)

Yet the crowds of tourists that flock to Seville to see its traditional attractions – the bull ring, the ancient cathedral and the Real Alcazar palace – rarely venture across the broad canal that separates the city from the Expo site, on the Isla de la Cartuja.

Science fiction landscape

That’s a shame, because not only is the site an Instagram paradise of sometimes post-apocalyptic science fiction landscapes – almost completely deserted on evenings and weekends – it’s filled with stories.

“Where else in the world can you find so many different examples of valuable architecture from this period?” asks Angel Aramburu, who as president of the Asociacion Legado Expo Sevilla leads a group dedicated to promoting and preserving the remaining buildings.

The group leads occasional tours of the site, filling visitors in on the fascinating gossip and intrigue behind the various structures.

Aramburu, who was only 12 when the Expo was staged between April and October in 1992, dreams of starting a tour company to bring in more people to see the buildings he loves. His youthful experiences infected him with a burning enthusiasm for the site and its treasures.

“I lived close to the Expo when I was a child, so when it opened I was seeing many things for the first time. Can you imagine what it was like? Before then I’d never seen anyone from China, Japan or any African country.

“So many things were a shock and a surprise, and when you get to experience something like that, you don’t want anything else in the world.”

Aramburu took CNN on his tour of the site. Here are the highlights:

Tower of Europe

The Avenue of Europe is a long and broad plaza populated by orange trees and strange cone-like structures that once cooled visitors in the height of Seville’s summer using an ultra-fine mist.

In the center stands the Tower of Europe, a multicolored obelisk decked out in the flags of the 12 nations that a year after the Expo ended would come together to form the European Union.

It’s a proud symbol of an era of optimism about cooperation in Europe – a continent that 23 years later is struggling to fulfill its original ideals of unity.

France Pavilion

At one end of the avenue, the once mighty pavilion of Spain has been occupied by Isla Magica (Avenida de los Descubrimientos, Isla de la Cartuja, Sevilla; +34 902 16 17 16), a popular theme park.

But opposite that is another poignant monument to better times.

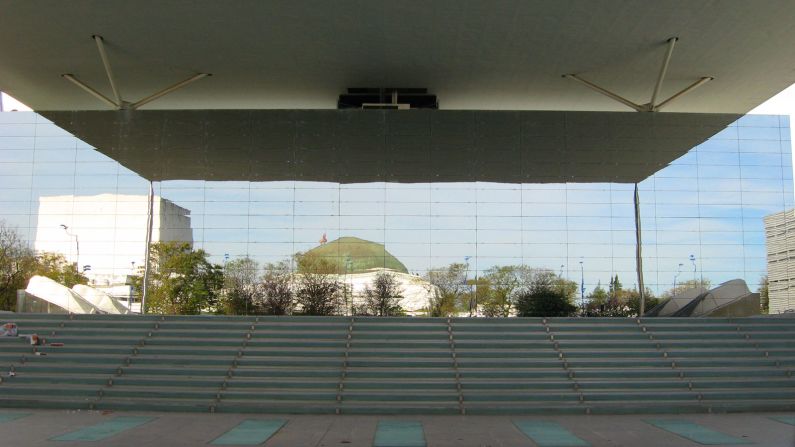

The French pavilion featured a giant canopy covering a huge wall of mirrored glass that in 1992 would’ve reflected the Spanish structure.

“In 1992, Spain had so much going for it,” says Aramburu. “Madrid was named as the cultural capital of Europe, we hosted the Olympic Games and the World Expo.

“Every country in Europe wanted what Spain had in ’92, which is why France chose to build something that reflected Spain’s pavilion.

“It’s hard to imagine that now, when you look at the economic troubles facing Spain.”

Hungary pavilion

Aramburu’s favorite building on the site is a strange, bulbous structure that’s part church, part owl, part political insult and part whale.

Designed by Budapest-born naturalist architect Imre Makovecz and considered one of his masterpieces, the Hungarian pavilion catches the eye against neighboring structures of concrete, glass and metal.

The wooden building, which contains a tree with its roots embedded in glass, features shamanic symbols as well as spires that represent all major religions.

One side is a dark facade with a giant animal mask that Aramburu says was a deliberate snub to the Vatican, which had a neighboring pavilion.

The other side is white, a friendly gesture to Austria and to the West to which post-Communist Hungary was now looking.

The bizarre structure, now listed as a protected building, is currently for sale with an asking price of $1.1 million. The Expo group hopes a tenant can be found soon to ensure its preservation.

Chile pavilion

Another wooden building that’s on the market for a new owner, the Chilean pavilion also tells tales from of a political past.

In 1992, Chile had only just emerged from years of dictatorship and wanted to prove itself as a modern and trustworthy democracy, capable of anything.

And so for the Expo, says Aramburu, it conjured a bold piece of theater – sawing up an entire iceberg plucked from its freezing southern oceans, transporting it to searingly hot Seville, and reassembling it inside its cool pavilion.

Kuwait pavilion

In 1992, Kuwait was another country needing to project its identity on the world stage, having two years earlier been invaded by Iraqi troops under Saddam Hussein.

The result is a spectacular wooden structure whose cantilevered roof was once capable of unfurling like the interlaced fingers of clasped hands.

The roof no longer moves, but anyone willing to sit through the video to “When We Dance” by Sting can still see it in action here.

Mexico pavilion

The brutally modernistic Mexican pavilion is intended to reflect the structural style of an Aztec pyramid, but also features a visual pun in the shape of a giant X.

Aramburu says the X is intended to convey the country’s position as a “crossroads of cultures,” but also remind people that despite it’s silent pronunciation in Spanish, the word Mexico contains the letter X.

A model of an Aztec city was built on the roof – glimpses of it can be seen from street level.

Cartuja Monastery

Seville’s role as Expo host capitalized on a nice historical symmetry since 1992 was the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to “discover” the New World.

Prior to his departure, Columbus received a blessing at a monastery on Cartuja. His remains were supposedly interred there at a later date.

In intervening centuries the monastery was used as a ceramics factory then abandoned and allowed to fall into disrepair.

Expo 92 gave the city an excuse to restore the building to its old glory.

Its grounds were used to welcome world leaders to the Expo and showcase modern artworks from participating nations.

Today it hosts the Andalusia Contemporary Art Center (Calle Americo Vespucio, 2, Seville; +34 955 03 70 96) a modern art museum with a surrealistic exterior.

Other highlights:

The “Seville rocket”

An exact replica of the European Space Agency’s Ariane Four launch system towers over what was Expo’s Pavilion of the Future and now hosts major entertainment events.

New Zealand pavilion

This one features a replica of the cliff first seen by explorer James Cook which, during the Expo, was populated by animatronic penguins.

Monaco pavilion

A facade resembling the Casino de Monte Carlo hides a building full of fish. Monte Carlo’s aquariums were later given to Seville’s river authorities who use them to study local aquatic life.

Canada pavilion

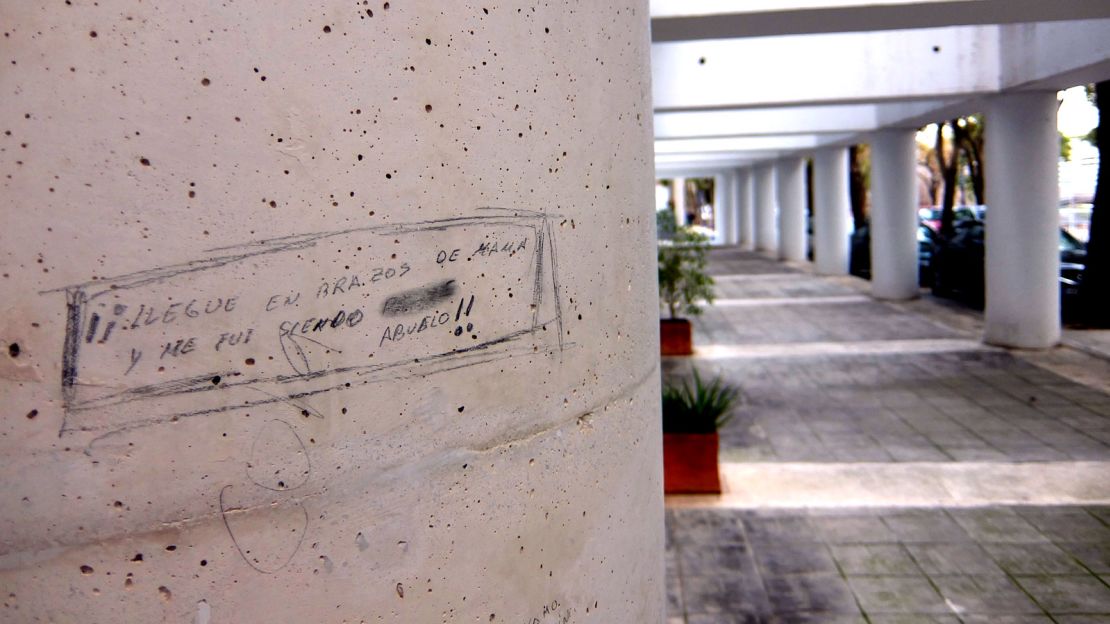

Architecturally nothing special, but the 1992 graffiti (the Twitter of its day) that still covers its external pillars testify to the Expo popularity of a giant cinema screen that had people lining up for hours.

Such were the queues for the Canadian pavilion that one wag carved a complaint in a column outside: “I came in the arms of my mother, I left as a granny!!”

Discoveries pavilion

Alas, this didn’t even make it to the Expo, burning down before it opened.

An adjoining Omnimax (an IMAX variation) theater survived, but because of the fire it was later demolished to make way for a 38-story tower block, the tallest building in Seville.

“I know it’s progress,” says Aramburu, “but I’d rather have the Omnimax.”

Contact the Asociacion Legado Expo Sevilla at contacto@legadoexposevilla.org