Editor’s Note: Call to Earth is a CNN editorial series committed to reporting on the environmental challenges facing our planet, together with the solutions. Rolex’s Perpetual Planet Initiative has partnered with CNN to drive awareness and education around key sustainability issues and to inspire positive action.

It’s just past 7 a.m. on a February morning in Maya Bay, several weeks after authorities reopened what is one of Thailand’s most popular tourist attractions to the world for the first time since June 2018 following a massive rehabilitation program.

A lone tourist walks along the shore, the towering limestone monoliths appearing to float over the surface of the water, their bases eroded by millions of years of lapping salt water. In the distance, blacktip sharks swim through the bay, their fins breaking the surface.

It’s a surreal scene, having this spectacular cove largely to oneself.

In the hours to follow, a slow but steady trickle of arrivals becomes a deluge as dozens of tourists trudge down a newly erected boardwalk, making their way to the celebrated white-sand beach, phones at the ready as they take selfies and pose for photos.

Those who venture more than a few steps into the water are met with loud whistles from a park official overlooking the beach from a sheltered lifeguard tower nestled in the trees edging the sand; swimming is not allowed, though visitors can wade a few steps in.

But some tourists are seemingly unable to resist the aquamarine waters of the bay and attempt to push the boundaries. One French tourist is issued a 5,000 baht fine (about $137) for repeatedly ignoring the rule.

On the boardwalk, an elderly woman furtively smokes a cigarette near the entrance to the beach – a strictly no smoking area.

It’s disheartening, but a huge improvement over what visitors once experienced here.

The beach that was loved to death

Located in Thailand’s Hat Noppharat Thara-Mu Ko Phi Phi National Park, Maya Bay is part of the uninhabited Phi Phi Leh, one of the two main Phi Phi islands, in Krabi province.

For Thai authorities, balancing the need for travelers – tourism contributed about 20% to Thailand’s GDP prior to the pandemic – with the urgent call to protect the park’s precious natural resources is an ongoing challenge.

“The best solution is nobody comes,” says marine biologist and professor Dr. Thon Thamrongnawasawat.

“If you ask me as a scientist, keep the bay for the sharks. But as we know, the bay is a big tourism spot. So we have to compromise.”

Thon is widely credited with convincing authorities to indefinitely close the bay four years ago – a controversial decision at the time.

Leading a team of marine scientists, he worked with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment alongside the private sector – namely, property developer Singha Estates, which has put sustainability at the forefront of its operations – on the massive rejuvenation project that took place in the absence of tourists.

“Around 40 years ago, Maya Bay was already a tourism destination, but (mainly) only for Thai tourists – and not so many because you didn’t have speed boats at that time,” Thon says.

“More and more people came. And then there was that movie from Hollywood.”

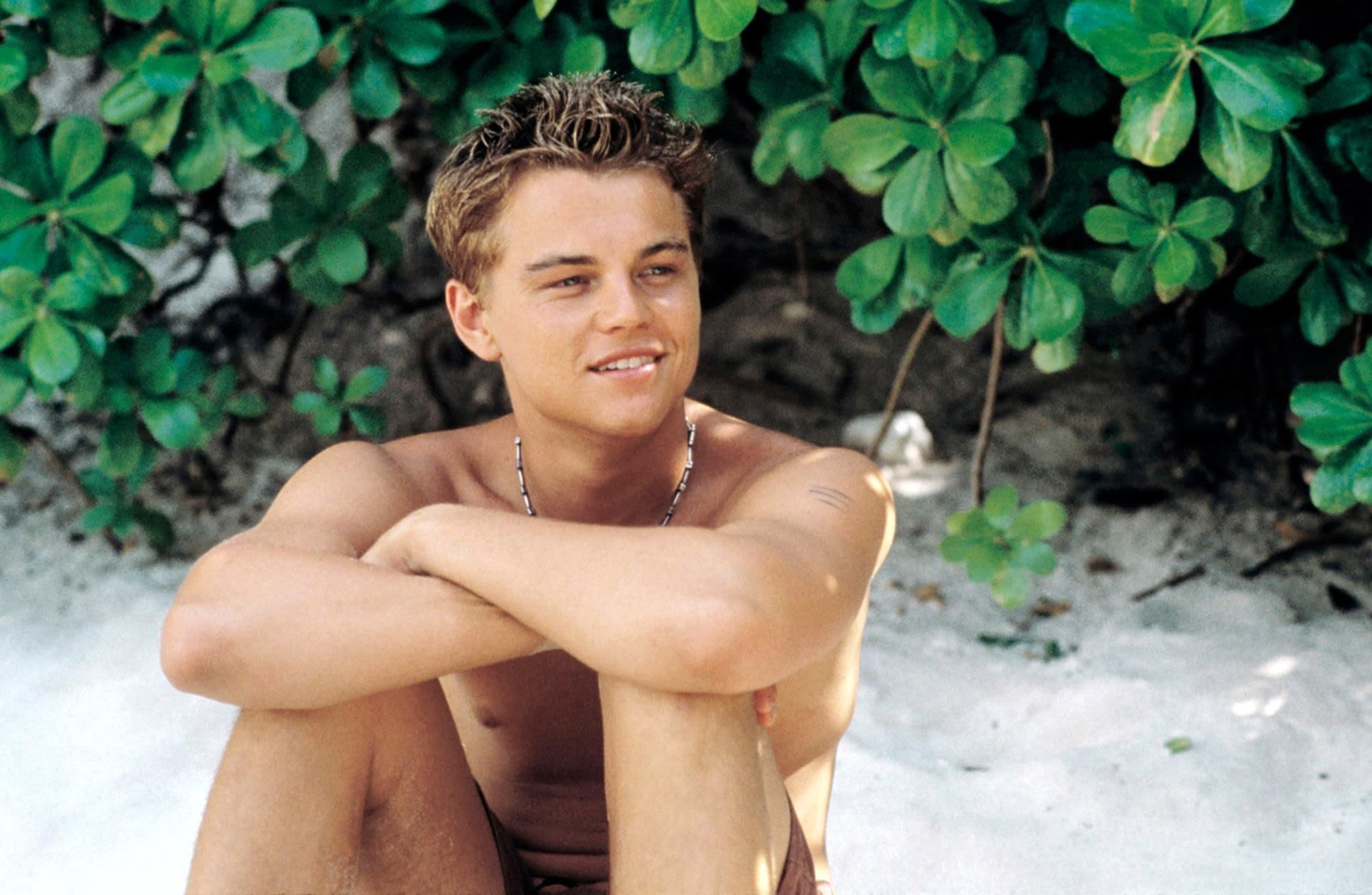

‘That movie’ of course being “The Beach,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Released in 2000, it focused on a group of backpackers looking to create their own private utopia on an unbelievably beautiful island in Thailand.

As the film’s popularity grew, so too did tourists’ desire to visit the location where much of it was shot – Maya Bay.

Over the years, the number of tourists increased from less than 1,000 to as many as 7,000 or 8,000 visitors a day at its peak, says Thon. Many were daytrippers visiting from nearby Phuket. On average, around 5,000 people entered the bay each day.

“There were a lot of boats coming in,” he recalls. “I used to check using a drone and I found almost 100 boats at the same time.”

The boats’ propellers whisked sand up onto the coral, their anchors slamming down onto the delicate sea floor. Incoming tourists walked on the reef as well, most unaware of the damage they were doing.

Thon says they first checked on the corals around 30 years ago, and 70-80% of the bay’s reef was intact.

Years later, less than 8% remained.

Aside from important ecological concerns, the tourist experience was not a positive one either. Panoramic views of the beautiful bay were blocked by the long line of boats anchored along the shore.

Since closing the bay in 2018, Thon and a team of fellow marine experts and volunteers have replanted over 30,000 pieces of coral, much of it grown off the coast of a nearby island, Koh Yung.

About 50% of the replanted coral survived – there was some bleaching – and now it’s starting to grow and spread on its own. As Thon says, “mother nature is doing the job.”

Without the transplanting process, he says it would take 30-50 years for the reef to regenerate naturally.

Meanwhile, the wildlife also returned and has been thriving. Among the animals currently inhabiting the bay are clownfish, lobsters and blacktip sharks, which are harmless to humans.

“When we closed the bay, after only three months, the blacktip sharks came back, they keep on mating, some of them give birth … so there are a lot of things happening in Maya Bay, not only the coral reef.”

(See above video for more on the restoration project.)

A resurrected bay closes again

Now, a mere seven months since reopening, Thai authorities are closing Maya Bay once again.

This time, however, the closure will only last two months, from August 1 to September 30, during the monsoon season.

Authorities tell CNN they want to further improve the island’s infrastructure and give the protected area a break from the masses of tourists that have already returned to its stunning shores.

The closure comes as a reminder that a lot of effort has been put into rehabilitating this battered attraction, and authorities want to ensure those moves weren’t made in vain.

Suthep Chaikaow, current chief of Maya Bay national park, recalls the atmosphere before the park was closed in 2018.

“All I can say is that it was terrible,” he tells CNN. “In the past, when tourists tried to take photos, all they could see was the bay, flooded with anchored boats. The views were not beautiful. And the beach was also full of tourists.”

To remedy this, the Department of National Parks has limited the number of visitors to not more 4,125 persons per day, allocated into one-hour slots to spread them out. The first slot is at 7 a.m. and each slot cannot exceed 375 people.

Boats can no longer enter the bay. Instead, drivers have to drop passengers off at a newly built jetty set at the back of the island away from the famed cove – all part of the rejuvenation program designed to avoid the problems of the past.

A new boardwalk leading from the dock cuts through the forest, offering a pleasant five-minute walk through the forest to the beach on the other side of the narrow island.

And that swimming ban? The park director says there are a few reasons they want to keep tourists out of the water. For one, they will disturb the sharks. Also, he says some tourists are not good at swimming, and may step on the corals that scientists worked so hard to regrow.

“The corals can be broken, our natural resources could again disappear,” he says.

The current setup is a sufficient compromise.

“I feel very glad when I see visitors are happy. The before and after of (Maya Bay) are so much different… it’s encouraged us to preserve this area.”

Tourists CNN spoke with seem to agree.

“It’s like paradise,” says Nicole, a German traveler visiting Maya Bay for the first time.

“It’s a very good thing to do,” says one Thai tourist from Bangkok of the new rules. “For those who have not been, I recommend it as a once in a lifetime thing to see.”

As for the criticisms the government faced when closing the bay four years ago, a move that cut into the pockets of the many tour operators that arranged travel to the bay, park chief Suthep says most have since come around.

“The only thought of business operators was to have as much tourists as they could,” he recalls. “But after the shutdown, they sent representatives to witness the area. It was very surprising for them, they said if they knew it would turn out this way, we should have done it a long time ago. They have been cooperative.”

Protection through education

Just a 15-minute speedboat ride away from Maya Bay on nearby Phi Phi Don sits Saii Phi Phi Island Village Resort.

Owned by Singha Estates, its marine scientists worked closely with Thon on the Maya Bay restoration project – all part of a broader aim to usher in a new era of sustainable tourism in Thailand.

Among them is marine biologist Kullawit Limchularat, sustainability development manager for Singha Estates. He says the Maya Bay project is the most visible part of their efforts to protect and revive the entire area’s precious underwater life, but they are also invested in other important works to improve the region.

One such project that’s close to his heart is the resort’s brownbanded bamboo shark breeding program, called “SOS (Save Our Sharks)” which is managed through the resort’s Marine Discovery Centre. A large, well-planned facility, it’s designed to educate tourists as well as residents from neighboring communities about marine life and ecosystems in the national park, in effect cultivating environmental consciousness.

“The local community is the one who lives here. They need to know what did they have and how important it is to protect,” says Kullawit.

As part of the SOS program, staff manage every stage of the bamboo sharks’ development.

First, the juvenile bamboo shark embryos are brought to the center from the Phuket Marine Biology Center. The embryos take around 90 days to hatch.

When they reach 30 centimeters, they’re moved to the bigger shark tank, where they’ll live for another three months before they’re released into the ocean.

The center also breeds and releases a far more familiar fish that makes its home in Thai waters – the clownfish, or simply “Nemo fish” as most Thais refer to them colloquially thanks to the popularity of Disney’s “Finding Nemo.”

Kullawit says the captively bred clownfish in the center’s tanks will be released if local populations are depleted.

CNN joined Kullawit and other staff from the resort on an expedition to release the latest fully grown bamboo sharks earlier this year. (See video above.)

In accordance with Thai laws, the sharks cannot be released in national marine park waters as the sharks were bred in captivity, says Kullawit. Instead, the team must cruise several hours away to waters outside the protected area to a tiny, rocky outcrop known as Koh Mah – or Dog Island.

“We found that around this area has a lot of coral, and this is a perfect place for the bamboo shark, because this shark is the reef species, but they stay in the bottom,” says the marine scientist as he prepares to release several of the sharks bred in the center.

Carried down to their new home by a team of scuba divers, the sharks are timid at first, and reluctant to leave their brightly colored baskets. Eventually, they swim away, slowly.

“The bamboo shark is a small species,” says Kullawit. “They are not aggressive and play an important role in the environment because they are a predator. They will control the weak prey like weak octopus, weak small fish… the environment of the coral reef will be stronger.”

Bamboo shark numbers have declined in recent years due to fishing practices and habitat destruction, putting reefs like this one in jeopardy.

“If we do not have sharks, the ecology of the reef will be destroyed. When we release them, we feel like we give something back to nature.”

“I will keep my eye on Maya Bay”

According to a recent World Bank report, international tourist arrivals in Thailand are expected to reach 24 million, or around 60% of pre-pandemic levels, by 2024.

For now, the missing piece of Thailand’s tourism recovery puzzle is China, which continues to discourage its citizens from traveling internationally by imposing lengthy return quarantine restrictions.

Prior to the pandemic, Chinese travelers were the biggest source market for Thailand’s tourism industry.

When the masses of global tourists eventually do return at pre-pandemic levels, park officials’ commitment to sustainability will be put to the test.

But Thon is confident the success of Maya Bay can act as a model for other tourist destinations at risk.

“It will change the image of Thai tourism, share the image that we are not just a country that are crazy about money,” he says.

“We would like to save our sea. And we can, if we can do at the heaviest mass tourism spot in the Thai sea, we can do it everywhere. The Maya Bay project is one of my biggest projects in my life. So as long as I live, I will keep my eye on Maya Bay.”

CNN’s Kocha Olarn contributed to this report.