At Cattle Depot, a former slaughterhouse turned artists’ village in northeast Hong Kong, a man in a larger-than-life costume strides into view.

The “Live Body Installation” consists of layers of black and white clothing – including a pair of trousers flung over his shoulders as a cape – an abundance of DIY accessories, a white wig, and a tall hat containing a rotating light box.

This is Kwok Mang Ho, who’s known as “Frog King” in Hong Kong.

A pioneer of contemporary art in Asia, the 70-year-old multidisciplinary creative is a Hong Kong icon – not only for his over-the-top outfits, but also for his eccentric installations, conceptual ink paintings, street art, and prevalent amphibian motifs.

Throughout his 50-year career, he’s participated in more than 3,000 art events and exhibitions, including his “Frogtopia‧Hongkornucopia” show at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011.

And at Art Basel Hong Kong this week, the local artist will recreate his 1992 exhibition “The Art Mall: A Social Space,” originally shown at the New Museum in New York, in collaboration with 10 Chancery Lane Gallery.

“People don’t get Frog King at first,” Katie de Tilly, founder of 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, tells CNN Travel.

“They see his crazy costume and playful glasses and don’t take him seriously, although he is a very serious artist.”

Who is Frog King?

'Frog King': Meet Hong Kong's most eccentric artist

Born in 1947 in Guangzhou, a city in southern China, and raised in Hong Kong, Kwok says he decided to “devote [his] life to art” at a very young age.

“When the other children were making fire and candles, I carried one huge firework and held it with both hands and let it explode,” says Kwok.

“I was thinking, ‘Let’s see what’ll happen …’ My 10 fingers were bleeding and I was sent to the hospital.

“That was my performance with dynamite.”

In the 1960s,he studied calligraphy under New Ink Movement master Lui Shou-Kwa while pursuing a Fine Art degree at Hong Kong’s Institute of Education.

But Kwok quickly broke from tradition.

China’s first performance artist

Inspired by the modernist art movements of the 1960s – which championed mixed mediums and radical experimentation – Kwok began working with unconventional materials and everyday objects.

In 1979, for example, Kwok became the first performance artist in China with “Plastic Bag Happenings.”

In this series of art installations, he metaphorically collected people’s anxiety and fears into plastic bags.

Kwok tied up these “air sculptures” around Tiananmen Square, in Beijing, and The Great Wall.

The concept was unlike any “art” in China at that time, which made it hard for the public to understand.

“What I did 40 years ago, now they understand,” Kwok tells CNN Travel.

“With the development of the Internet, it helps to get the messages across faster. Maybe now I don’t have to wait for another century. I hope that society can accept and resonate with an artist when the artist is still alive.”

The installations further positioned Kwok as a radical thinker, and the pioneer of Hong Kong and China’s nearly nonexistent contemporary arts scene.

“If everyone understands what you are doing, that means what you are doing is already very common,” says Kwok. “That’s why I keep on doing art.”

‘I see two worlds’

As for his “Frog King” alter ego? That came a bit later.

After “Plastic Bag Happenings,” Kwok moved to New York where he immersed himself in the world of modern art and underground graffiti for the next 15 years.

When it came to choosing a street art logo, the buoyant amphibian seemed an apt choice, given the artists’ lifelong affinity for frogs.

“Frogs can see two different worlds: underwater and on land,” says Kwok. “As Frog King, I also see the two worlds.”

But more importantly, he adds: “Frogs represent happiness.”

The amphibian proved a perfect symbol – both for Kwok’s philosophy and his dynamic artwork.

“His works are spontaneous, creative, energetic and, for him, the most important part is that you feel the fun within his works,” says de Tilly.

“He reaches into his audiences and pulls out their laughter, engagement, their former child self.”

Art for all

Kwok returned to Hong Kong in 1995, where he continued to push boundaries with street art and installations.

A few of his more recent works include the ongoing Frog King Kwok Museum Project and a staggering “Graffiti Wall” along Queen’s Road Central, which doubles as the facade of H Queen’s Central – a new vertical art village.

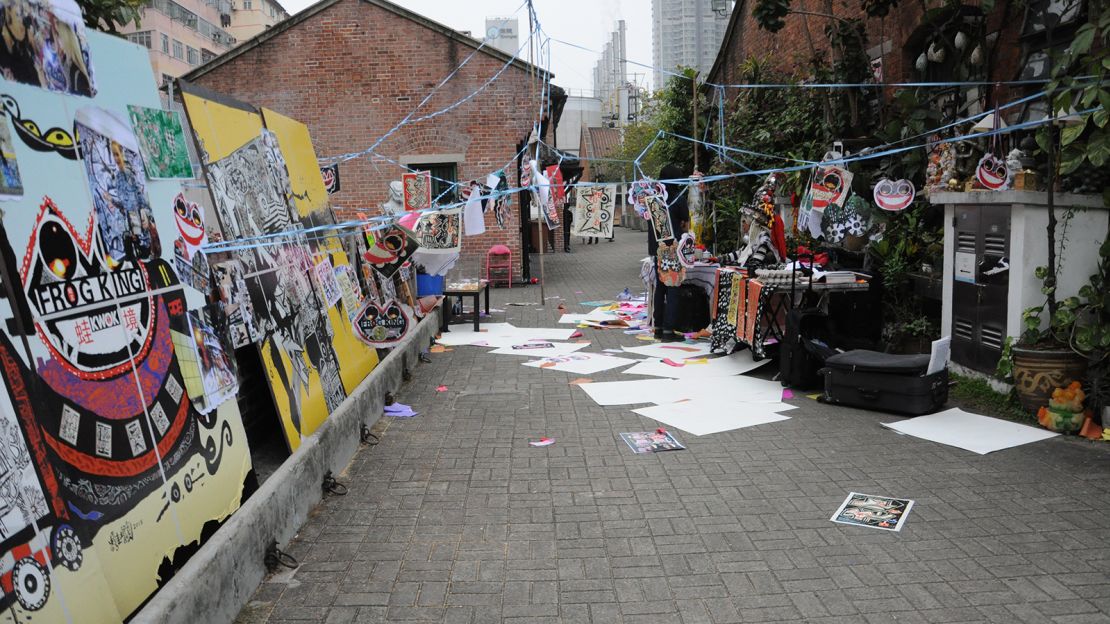

Kwok is the opposite of elusive. In fact, you can usually find the larger-than-life artist at the Cattle Depot in Ma Tau Wan.

Formerly a century-old slaughterhouse, the complex reopened in 2001 as an artists’ village, housing studios and galleries for about a dozen different creative parties.

“Opening Cattle Depot as an art village for the public has helped promote community art as it lowers the barrier for the public to enjoy and interact with art,” Wong Wing Tong, Kwok’s former assistant who now runs PlayDepot art space, tells CNN Travel.

“Frog King always invites visitors to wear his ‘froggy sunglasses’ and places a lot of artworks around Cattle Depot for the public to see and touch.”

Village life

Anyone can visit the village, meet the artists, and maybe even get hands-on – particularly if you find yourself at Frog King’s studio, which is crammed with thousands of old everyday objects – or “community heritage” as Kwok describes them – that were gifts from neighbors.

“My work is often free and I like giving out my work. I think art isn’t just for rich people,” says Kwok.

“Sharing my work is a direct way to pass down culture. Art should be classless.”

When we meet at his studio, Kwok distributes a pile of white placemats and encourages visitors to participate in his performance art.

“Tear up [the mat] and throw it out there to create a new dimension to space,” he instructs.

“Art is nonsense. But if you see it another way, being nonsensical is also a way of thinking. Through art, you can explore an unknown possibility in life.”