Remember that fuzzy little feeling called happiness?

In case you need a reminder: It was this word we used to use back in 2019 to describe a state of pure pleasure and contentment.

Happiness seems to have faded from our vocabulary amid the global pandemic, economic turmoil and, well, collective sense of doom and depression that is 2020. Which is why the opening of a new Happiness Museum in, where else, Denmark feels like the most optimistic story of the year.

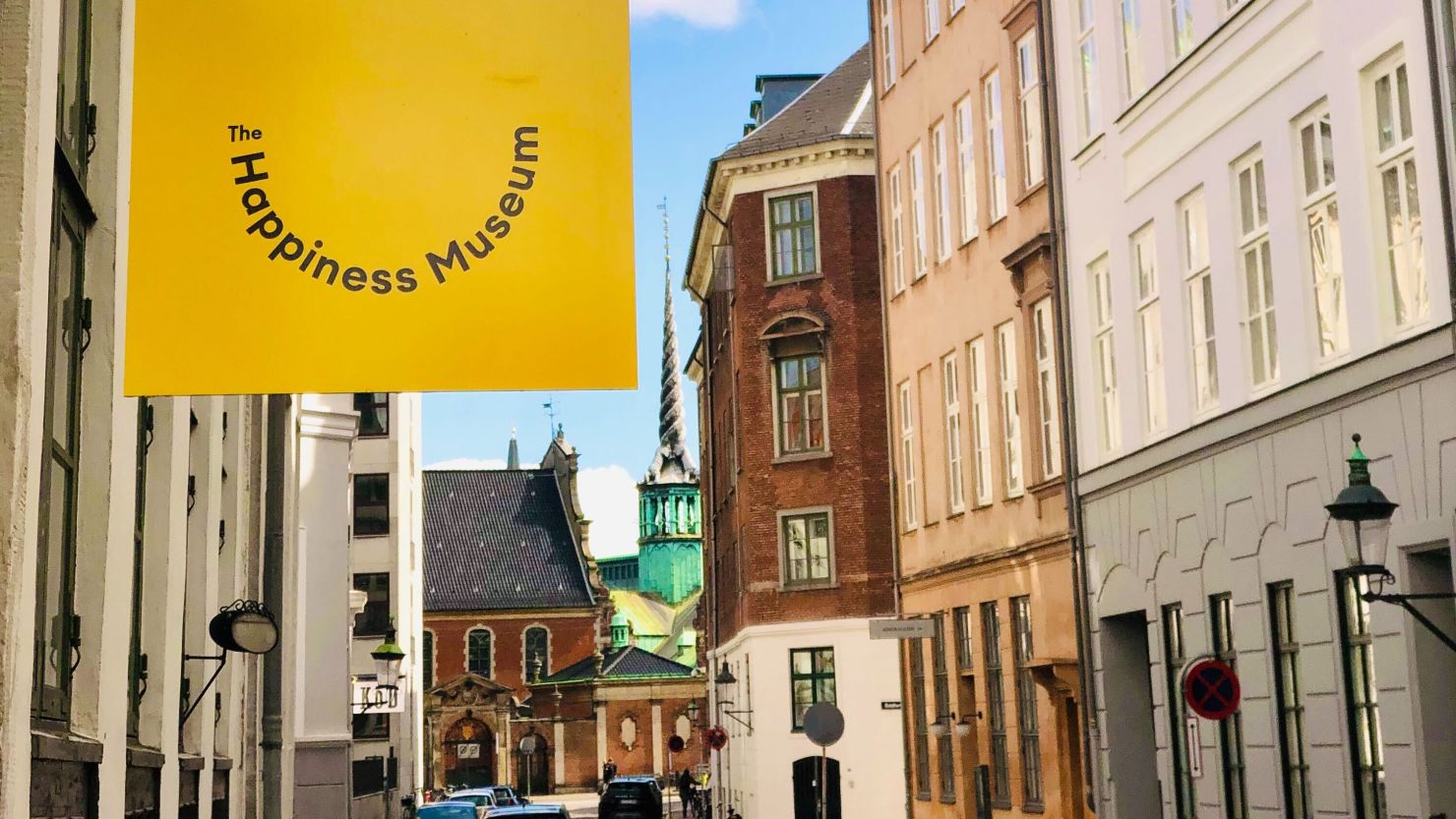

The world’s first museum dedicated explicitly to the concept of happiness had a quiet debut on July 14 in a cozy 240-square-meter (2,585 square foot) space in Copenhagen’s pastel-perfect historic center.

The new attraction is the brainchild of the Happiness Research Institute, an independent think tank that explores the science behind why some societies are happier than others with the end goal of encouraging global policymakers to include wellbeing as an integral part of the public policy debate.

Meik Wiking, CEO of the Happiness Research Institute, says the idea to open a museum came after years of fielding requests from the public about visits to their drab office space.

“I think people imagine that the Institute is like a magical place – a room full of puppies or ice cream – but we are just eight people sitting in front of computers looking at data,” he explains.

“So we thought, why don’t we create a place where people can experience happiness from different perspectives and give them an exhibition where they can become a little bit wiser around some of the questions we try to solve?”

An unusual time to open

The seed was planted and, by early 2020, the museum was nearly ready.

Then, of course, the pandemic closed international borders, and Wiking had to decide whether or not to go ahead with the opening.

“We thought, there might not be a lot of guests these days, but the world does need a little bit more happiness,” he recalls.

So, they set in place strict Covid-19 protocols – including a one-way traffic system and a cap of 50 guests – and opened their doors to the public.

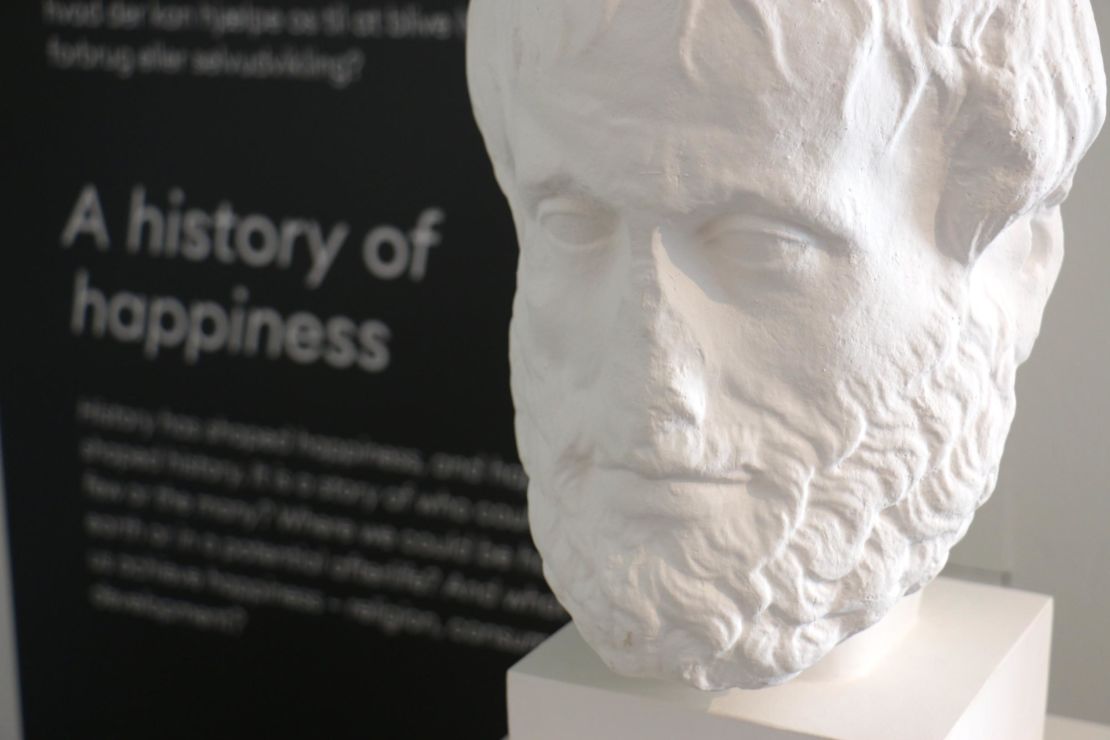

Ever since, the museum has given visitors a tour of global happiness, showing how perceptions of it have changed throughout history, what it looks like in different regions, and why some countries report more of it than others.

Along the way, there are also questionnaires and interactive experiences that aim to give guests “aha” moments, as well as enhance the Institute’s ongoing research.

For example, Wiking says trust toward fellow citizens and political institutions is a major factor in global happiness, which is why some visitors may come across a wallet filled with cash. Museum staff have periodically placed this wallet on the floor for more than a month now, and it’s been returned to reception (with all items inside) every time.

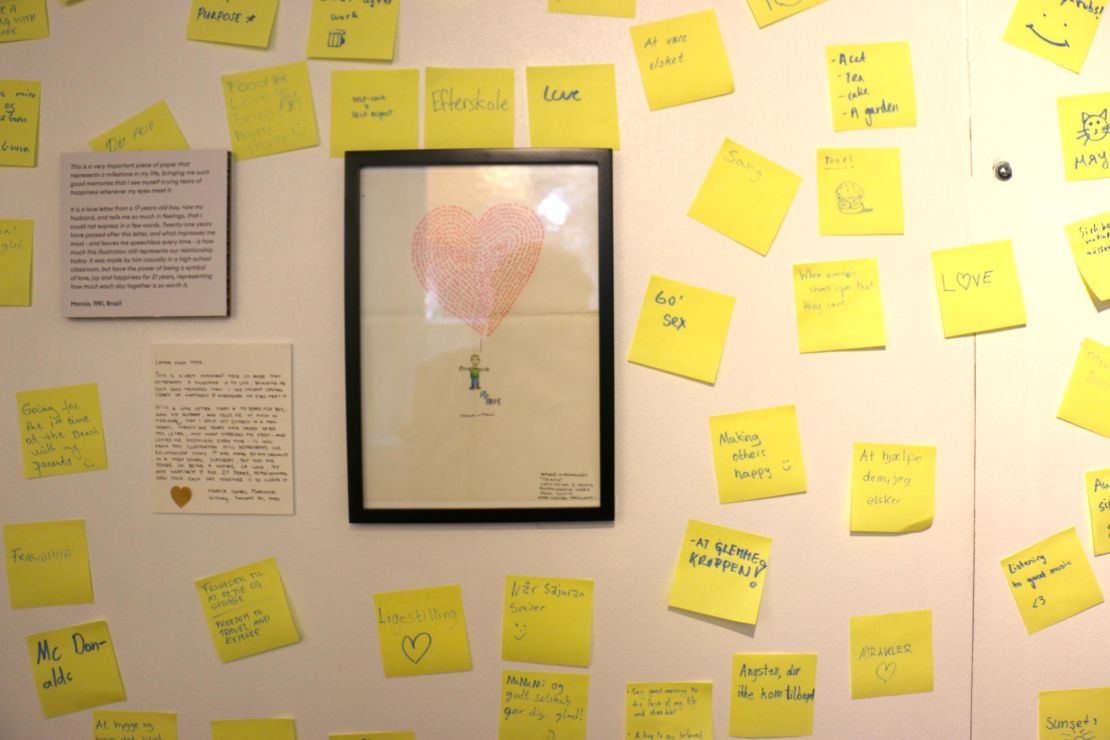

People from around the world have also sent in artifacts of happiness – things that represent joy to them – which form a large part of the display. These items are meant to help visitors contextualize what happiness looks like for others in different parts of the globe.

“We might be Danish or Mexican or American or Chinese, but we are first and foremost people,” Wiking says. “It’s the same things that drive happiness no matter where we’re from, and I hope that people will see that in the exhibition.”

One guest told him that he had always known he was a happy guy, but he had never before understood the reasons why.

“That, for us, was the best review we could get,” he says.

What makes nations happy?

One of the other main focal points of the museum is why Nordic countries tend to report some of the highest levels of happiness on earth.

Denmark, for example, frequently lands near the top of surveys ranking the world’s happiest nations, including the United Nations’ annual World Happiness Report. In its 2020 list, Denmark comes in at No. 2 just behind neighboring Finland, while Copenhagen ranks as the fifth happiest city in the world, behind Helsinki, Aarhus (also in Denmark), Wellington and Zurich.

Danish psychologist Marie Helweg-Larsen, a professor at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, says that “it boggles peoples’ minds how you can, just by thinking thoughtfully and strategically about the role of government in life, create happy people.”

Plus, the countries that report the highest levels of happiness tend to contain many elements that, at least on the surface, would seem to hinder it.

“I think foreigners find the Nordic countries to be kind of a conundrum,” Helweg-Larsen explains. “They seem to do things that others have decided couldn’t possibly be associated with happiness, like pay high taxes, live with cold weather and experience long periods of darkness.”

So, what might the rest of the world learn from the Danes in these trying times?

“Trust is a factor in happiness,” Helweg-Larsen says. “We could all do more to talk to people who are not like us and see how we can establish more trust in our own communities.”

She also thinks the Danish concepts of pyt (an “oh well” attitude for accepting a problem and resetting) and hygge (the pursuit of intentional intimacy within interactions and environments) are great for relieving stress.

Wiking says that, if his studies at the Happiness Research Institute have shown him anything, it’s that humans are incredibly resilient.

“When we follow people over time, we can see that they are remarkable at overcoming the challenges that happen to them,” he says. “Of course, it’s necessary to be optimistic in my profession, but I think we can overcome these times as well.”

As the Happiness Museum tries to share with its guests, happiness is a feeling that evolves and takes some nurturing both from society and from within. Work at it enough, and you’ll be better equipped to find the silver linings in these stormy days.