Every year on November 5, skies across England, Scotland and Wales are illuminated by fireworks as Brits head out into the night to enjoy Guy Fawkes Night celebrations.

Also called Fireworks Night or Bonfire Night, this autumn tradition has been a staple of the British calendar for the past 400 years.

Kids in English schools grew up reciting the nursery rhyme “Remember, remember / The fifth of November / Gunpowder, treason and plot.” But for those outside the UK, this rather unusual holiday’s rather unusual origin story may be a bit of a mystery.

Read on to find out more about the eponymous Guy Fawkes and how November 5th celebrations have evolved over four centuries.

Who was Guy Fawkes?

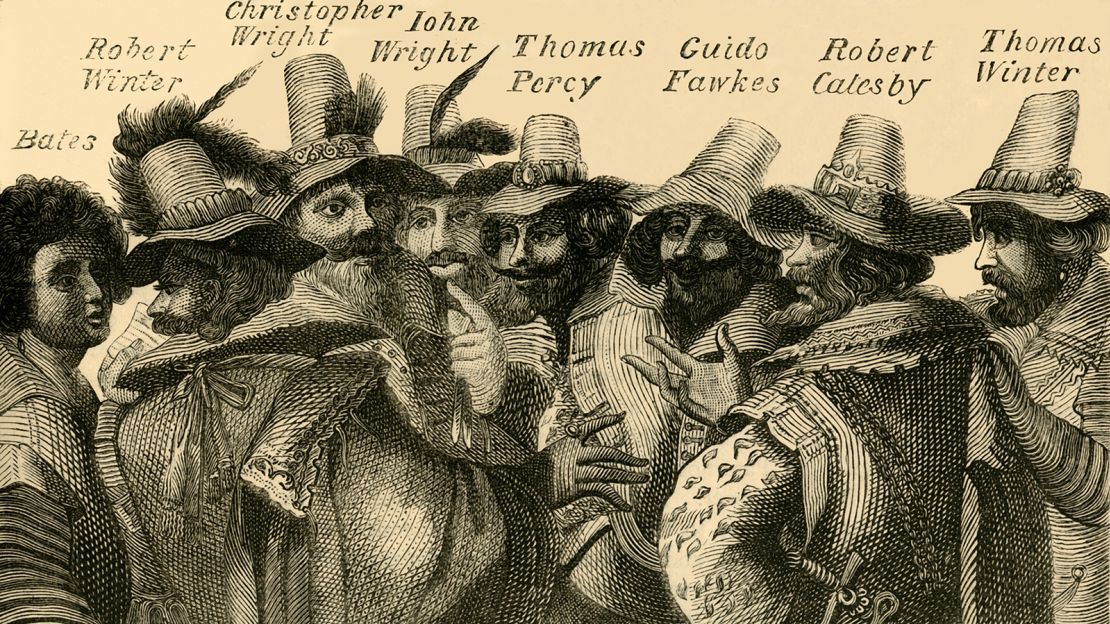

Guy Fawkes, sometimes known as Guido Fawkes, was one of several men arrested for attempting to blow up London’s Houses of Parliament on November 5, 1605. Fawkes and company were Catholics and hoped this act of terrorism would spark a Catholic revolution in Protestant England.

England had been a Catholic country until Tudor King Henry VIII founded the Church of England. In the aftermath, Catholics were forced to practice their faith in secret.

While Fawkes became the face of Bonfire Night, it was another plotter, Robert Catesby, who masterminded the idea. But Fawkes was an explosives expert, and he was the one who got caught under the Houses of Parliament next to the stash of gunpowder, hence his notoriety.

Catesby, Fawkes and their co-conspirators were imprisoned in the Tower of London and subsequently tortured and killed publicly.

Following the thwarted plot, Londoners lit bonfires in celebration, and then-King James I passed an act of law designating November 5 a day of national remembrance.

“When the news of the plot broke, or to be accurate, the news that the plot had been foiled broke, people spontaneously lit bonfires, and I think the tradition has just kept on from there,” historian James Sharpe, professor emeritus of early modern history at the University of York, tells CNN Travel.

As the century rolled on, people started burning effigies of the pope on bonfires on November 5. In time, effigies of Fawkes replaced the pope.

Sharpe, author of “Remember, Remember: A Cultural History of Guy Fawkes Day,” suggests that the act of law, which stipulated a thanksgiving church service, was a big factor in the celebrations continuing over the ensuing centuries.

There are contemporary reports of civic feasts, explains Sharpe, and later fireworks.

From the late 19th century onward, the religious overtones of November 5 dampened, and the act of law designating it a day of remembrance was repealed.

Still, bonfires and celebrations continued. It became a common sight to see kids trawling English streets with their homemade Guy Fawkes effigy, knocking on doors and asking for a “penny for the guy,” a kind of Bonfire Night-themed trick-or-treat.

What’s Guy Fawkes Night like today?

Britain is now a secular, multicultural society, and so it’s quite surprising that a celebration once steeped in anti-Catholic sentiment has endured.

Historian Ronald Hutton, professor of history and author of “The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain,” tells CNN Travel that Guy Fawkes Night’s endurance is in large part to do with its association with fire and light as well as the time of year in which it falls.

While the holiday was once “a distinctively nationalistic, Protestant festival with a specific hatred of Roman Catholicism,” Hutton says Guy Fawkes Night “no longer has any religious connotations to encumber it.”

Instead, Hutton suggests November 5 serves as a “rather spectacular, popular and secular festival at a time of year when people badly need cheering up.”

November 5 firework displays are now more commonplace than bonfires. While some people still light their own fireworks in their backyards, many head to community-organized events in parks and public spaces. That shift, explains Hutton, occurred in the latter half of the 20th century as commercial fireworks became readily available.

That’s also around the time when effigy-burning fell out of fashion – with a few notable exceptions. “Compared with the joy of the fun of fireworks, the work of the dubious satisfaction of burning people in effigy became a lot less exciting,” says Hutton.

In turn, kids also no longer beg for a “penny for the guy.”

Still, while you’re less likely to see a burning Guy Fawkes atop of a bonfire in current times, the conspirator remains one of the UK’s most famous historical figures. His image is also the inspiration behind masks worn by anti-establishment protestors across the globe.

Lewes Bonfire Night celebrations

While many British towns and cities no longer include effigy-burning in their celebrations, the small town of Lewes in the south of England is a notable exception.

On November 5 (or on the 4th if the 5th falls on a Sunday) several torch-lit processions parade through the historic town, featuring thousands of people, many in fancy dress. Celebrations culminate in large-scale bonfires featuring giant effigies.

The events are organized by Lewes’ six bonfire societies. Historian Hutton suggests it’s the longstanding existence of these societies that’s kept Lewes’ bonfire traditions going.

“These are very large-scale events,” he says. “They’re organized by bonfire societies in cooperation with each other, that can take months and months in preparation.”

The fancy dress celebrations have come under significant criticism. Until recently, some members of the Lewes Bonfire Society dressed up in Zulu-style costumes with blackface. In 2017, the group vowed to drop this practice.

In the past, effigies of former US President Donald Trump and former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson have been among those burned in Lewes.

The town council distances itself from the celebrations and discourages Guy Fawkes Night visitors.

“Lewes Bonfire is an event for local residents only, and we ask that people do not attempt to travel in to the town to spectate,” reads the Visit Lewes website. “The streets are narrow, and the combination of dense crowds, flaming torches and firecrackers can be dangerous.”

The 2023 event, set to take place on Saturday November 4, is set to be live streamed.

Ottery St Mary Bonfire Night celebrations

Another small town in southern England, Ottery St Mary, is also famed for its Bonfire Night traditions. On November 5 (or the 4th if the 5th falls on a Sunday) tar barrels are set alight and paraded down the streets.

Both Lewes and Ottery St Mary’s traditions have their origins in “rumbustious disorderly celebrations often carried out by youths,” as historian Hutton puts it.

Like Lewes, Ottery St Mary’s formalized its November 5 disorder in the 20th century. Flaming tar barrels, once rolled through the streets, are now carried by members of the community.

Journalist Patrick Kinsella attended the festivities in 2014, writing about the experience for CNN Travel and calling the sight of a man holding a flaming barrel, “the maddest thing I’ve ever witnessed.”

Bonfire Night food

There’s usually a chill in the air on November 5 in Britain, and over the years, certain comfort foods have become synonymous with the holiday.

Toffee apples (called caramel apples in North America) are seen as traditional Bonfire Night treats across England, Wales and Scotland. In Yorkshire in the north of England, a type of traditional ginger cake called parkin is often eaten.

In Lancashire, also in the north of England, there’s also a tradition of eating black peas – peas cooked in vinegar.

Hutton, meanwhile, recalls his childhood in the south of England grilling sausages on the bonfire. Sharpe, who grew up in Fawkes’ home county of Yorkshire, also recalls Bonfire Night sausages – served up in the traditional English form of “bangers and mash.”

The rest of the UK

Bonfire Night is principally celebrated in England, but there are also organized festivities across Scotland and Wales.

However, the holiday’s original anti-Catholic associations means the holiday isn’t celebrated in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland.

Instead, across Ireland bonfires are traditionally lit at Halloween instead, a tradition descending from the Celtic Festival of Samhain.

Incidentally, historian Sharpe suggests that the enduring popularity of Guy Fawkes Night in England could be in part because of the established precedent for fiery winter celebrations at this time of year – namely Samhain, as well as the Catholic holidays of All Hallows Eve, All Saints Day and All Souls Day.

Americanized Halloween celebrations have grown in popularity in Britain in recent years, and these days, October 31 celebrations often bleed into Guy Fawkes Night. Indeed some might argue Halloween’s overtaken Bonfire Night in popularity in the UK.

Still, if you’re going to be in England, Scotland or Wales on or around November 5, you’ll definitely spot a firework or two.

Of course, Lewes discourages outside travelers, but if you find yourself already there, Hutton suggests the perfect Bonfire Night starts with a local Lewes pub dinner before heading out into the cold night air to watch the festivities. He recommends heading to Ottery St Mary for a more chaotic experience.

Meanwhile, Sharpe suggests heading to York, where Fawkes was from, and checking out the array of local celebrations there. You’ll likely need a ticket in advance, so check out the local websites for details.

Meanwhile in London, there are organized, ticketed firework displays across the capital.

One of the largest is the Alexandra Palace Fireworks Festival in north London, offering a panoramic view of the city. South of the river, Battersea Park Fireworks offers pyrotechnics in a park neighboring the newly renovated Battersea Power Station, which once supplied a fifth of London’s electricity.