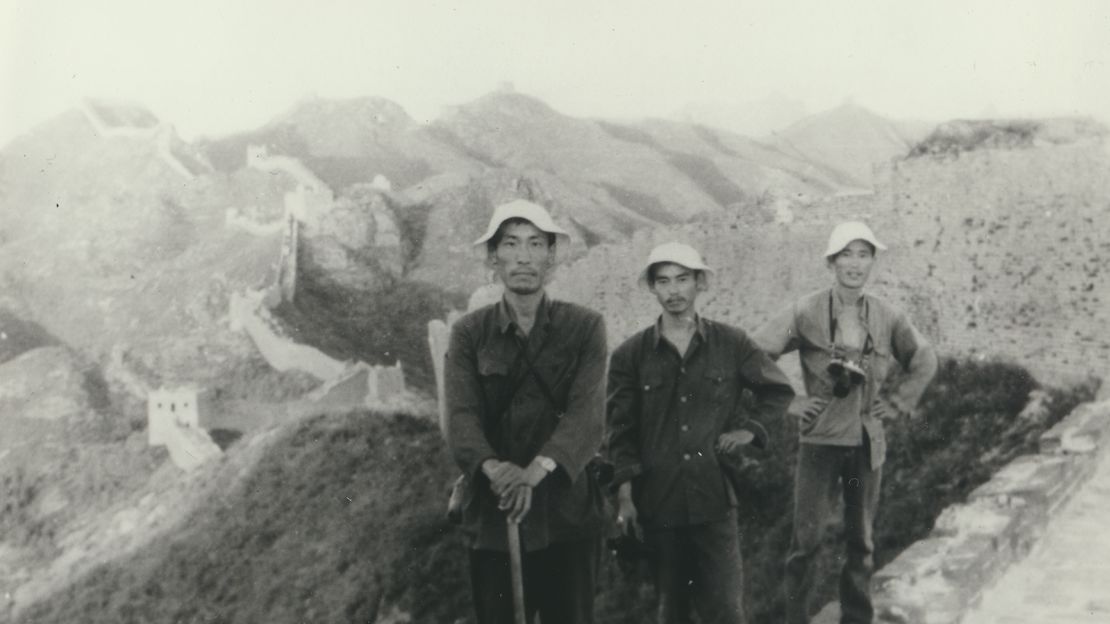

On a warm spring morning in 1984, Dong Yao-hui and his two young friends, Wu De-yu and Zhang Yuan-hua, pulled on military surplus backpacks and boots and set out on a hike along a stretch of the Great Wall of China.

Their walk began at Laolongtou – or the Old Dragon’s Head – in Shanhai Pass, where what was once believed to be the easternmost stretch of the Wall reaches into the Bohai Sea. From there they forged westward toward the mountains of Hebei province and the vast Chinese territory stretching out beyond.

By sunset the first night, they’d made good progress and took shelter in a crumbling fortification that, centuries ago, had accommodated the men who once stood guard on the Wall, perhaps watching for invaders from the north.

There they contemplated the journey ahead of them – a walk of 17 months and 8,850 kilometers (5,500 miles) that would test their endurance, but also take them into the record books as the first people ever to walk the length of the wall.

It was a trip that would not only change the lives of the three friends but would change the fortunes of the wall itself, helping preserve it and elevate it to the revered status it holds today.

First Great Wall expedition

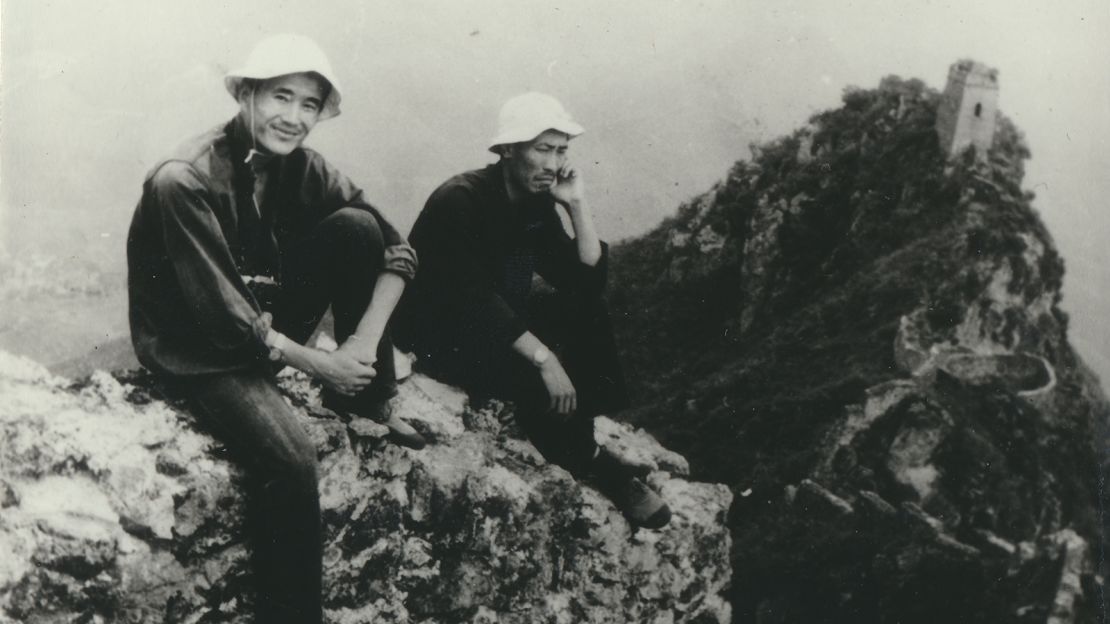

“It was the first time ever for humans to go on an expedition of the entire Great Wall, leaving the first complete set of footprints,” recalls Dong, now 62. “It was a nonstop uphill and downhill journey.

“The heat from summer, the snow in winter and the exhausting hikes were all challenging but they weren’t insurmountable. We just walked and walked and we made notes of what we saw. It was very repetitive like how a farmer tends to his farms.

“Little did we know when we were on the journey that it would end up becoming a lifelong project.”

Back in May 1984, the Great Wall was famous beyond China as the structure that could – so the legend goes – be seen from space. At that time, however, more was perhaps known about the surface of the moon than the contours of the wall.

Work on it began more than 2,500 years ago, its origins dating back to China’s Spring and Autumn Period of around 770 BC to 476 BC. Various sections were added in subsequent eras as competing dynasties and factions sought to exert their control.

Work eventually stopped in the 17th century. Today the wall reaches over 21,000 kilometers, winding its way through 15 provinces, 97 prefectures and 404 counties.

And while certain parts had long attracted tourists, both from within and outside of China, such was its size that by the 1980s – when the country was emerging from the turmoil of its 1949 communist takeover and the excesses of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s – many sections had slipped into obscurity, disrepair and sometimes oblivion.

This is where Dong enters the story. At 25, he was working as a power cable technician – and poet – in his hometown of Qinhuangdao, close to the Shanhai Pass, where he would later start his odyssey.

“I climbed power towers, often next to the Great Wall,” he recalls. “Slowly, I developed an interest in the Great Wall. ‘Who built it? When was it built? Why was it built?’ I had all these questions but there weren’t a lot of books you could read about it – not even the government had such a record then.”

Soon Dong’s interest formulated into a plan. And after two years of preparation, he and his two friends embarked on the epic trek that they thought would take them three years, but would in fact be completed in just 508 days.

An unexpected lifelong project

Dong, Wu and Zhang decided to focus only on the 8,851.8-kilometer Great Wall stretch that was restored and built during the Ming Dynasty – around 600 years ago. It’s the most well-preserved section and the part most commonly referred to when we talk about the Great Wall today.

“Our hiking outfits were military uniforms provided by troops stationed at each area,” recalls Dong. “Our rucksacks were donated by China’s Mountaineering Association – which were used during their expedition to Mount Everest. We were considered well equipped in the olden days.”

Instead of referencing a map, they simply followed the wall and recorded their own path on paper as well as their observations on the wall’s condition. At night, they usually slept inside the wall’s gates and fortresses, which were physically separated from the main structure, so they could document them too.

“Little did we know when we were on the journey that it would end up becoming a lifelong project,” says Dong.

On completing their journey, the expedition team spent the following two years consolidating and publishing their experiences in a book titled “Ming Dynasty Great Wall Expedition.”

But what they initially thought would be the end of their obsession with the Great Wall would transpire to be just the beginning as the repercussions of their journey rippled much further than expected.

“We had another plan originally to trek along China’s 18,000-kilometer seashore,” says Dong. “But our affair with the Great Wall was unstoppable once ignited.

“The further I went, the more it became a responsibility to society rather than just a self-fulfilling project.”

As they shared tales of their adventures, it became clear to the trio that it was not just the physical demands that left lasting impressions, but also the emotional impact of seeing how much of the wall had fallen into ruin.

So much so that they alerted authorities.

“When we told the ruling officials they said, ‘Right. Right. Right,’” Dong says. “But actually no one took it seriously, so we felt pain.

“Just think how tiring it was for us to walk the Great Wall, let alone how it must have been to build it. But today we keep taking it apart. So is society more civilized now? Or more idiotic?”

Today Dong comes across as a gentle, scholarly figure, one who has dedicated more than half his life to the study and preservation of the Great Wall, but contemplating its parlous condition revives the youthful indignation that propelled him on his original quest.

“Yes, I admit I can be reckless and emotional when talking about the damage sometimes,” he says. “It’d be better if I could deliver my message in a more rational and gentle way.

“But I can’t control it. I’m so upset – it’s a pain that comes from the bottom of my heart.”

Dong’s anguish isn’t without justification, with the wall continuing to face threats. In 2014, the Great Wall Society, which Dong founded and is now vice president of, reported that only 8.2% of the structure was in good condition.

Then, in 2016, sections of the wall came under scrutiny after it was discovered locals were smoothing over the ancient bricks with cement.

Dong tries to put such stories in a positive light, saying the fact that these issues are even appearing in the news suggests there’s been a change in attitude regarding the Great Wall.

“In these 35 years, the effort to protect the Great Wall has changed [immensely],” he says.

“Before the nation reformed, every village was destroying the Great Wall so it wasn’t considered news. Today, the media fights to report on it and people condemn it. The overall awareness of Great Wall preservation has improved.”

Cable technician-turned-‘Son of the Great Wall’

Dong can, of course, take a lot of credit for this. These days he’s known as the “Son of the Great Wall,” with a reputation as its leading authority. When US Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton visited the wall, he was their designated expert guide.

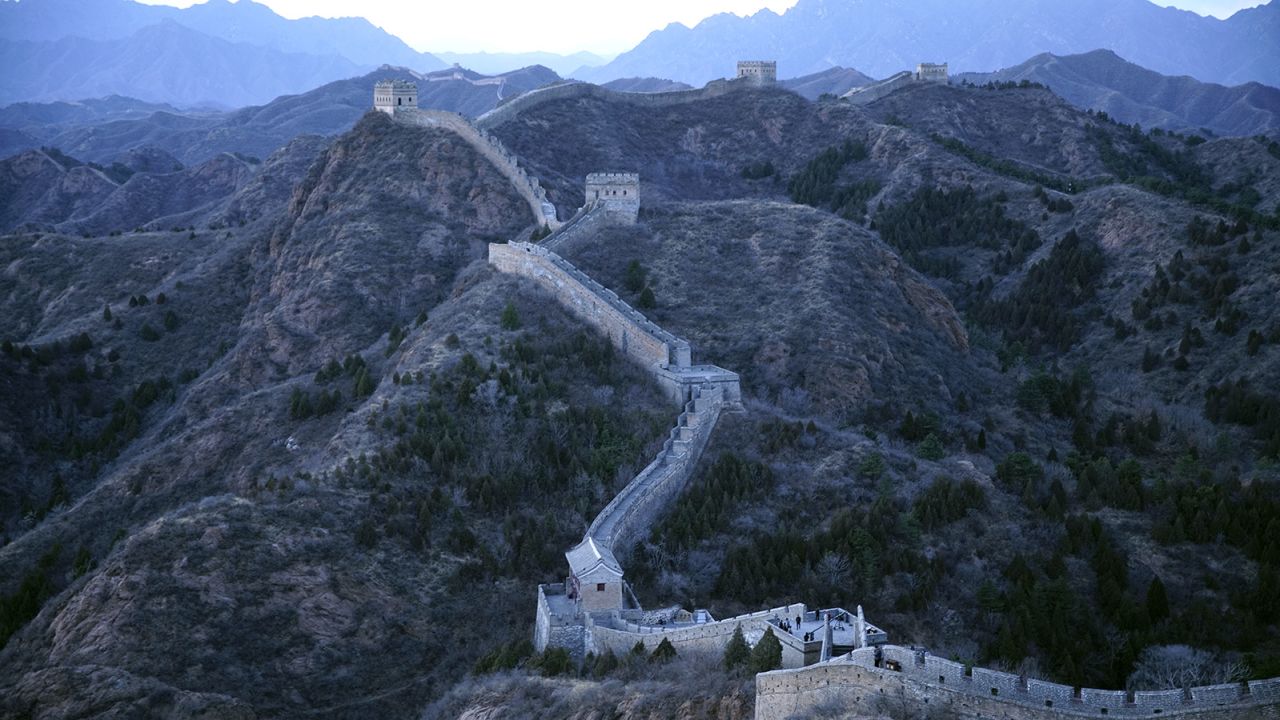

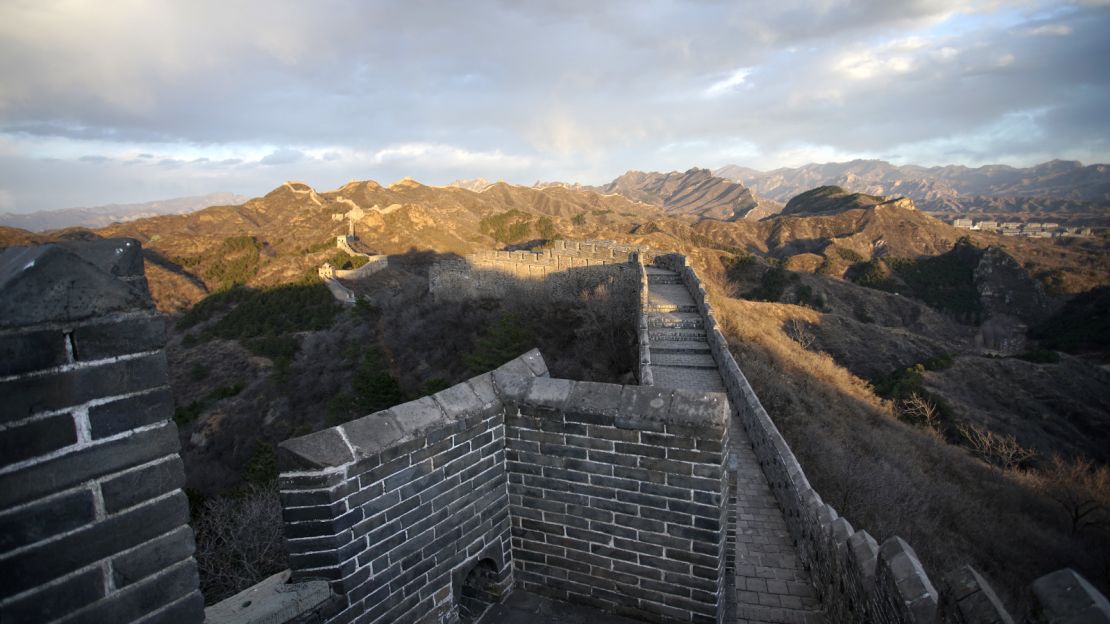

The respect conveyed on Dong is on display on another spring day earlier this year as CNN Travel joins him during a visit to the Jinshanling section of China’s Great Wall, in Hebei province, about two and a half hours northeast of Beijing.

Wearing a modest checkered shirt and a pair of dress pants, he is welcomed by a village of local officials and managers, before putting on a red hiking jacket to climb up the wall’s stairs, his agile frame always a step ahead of the crowd.

“Mr. Dong hasn’t been here for a while now,” one of the managers says with a broad grin, before updating the special visitor on the status and conservation works happening along this section of the wall.

The bespectacled scholar quietly nods and occasionally whispers short inquiries.

Work to preserve the Great Wall began in earnest in 1987 – three years after Dong’s hike – when UNESCO inscribed it was a World Heritage Site. Since then, China has implemented a number of measures to protect the world-famous attraction.

In 2006, for instance, the State Council issued the Regulation on the Protection of Great Wall to strengthen laws surrounding its preservation and regulate activities carried out on the structure.

The Cultural Relics Administrative Department was given control over the overall protection of the Great Wall.

Meanwhile, a new daily visitor cap of 65,000 has recently been implemented at the popular Badaling section of the Great Wall to improve the overall experience and prevent deterioration. A three-grade warning system will also be deployed to warn tourists about the size of the crowd on the wall – all in real-time.

Other measures include the demolition of a heavily commercialized tourist market at the foot of Badaling. It’s to be replaced with a Great Wall-themed cultural square by 2022.

In Beijing, China’s first Great Wall Restoration Center will be established this year, showcasing the seemingly invisible but meticulous restoration works on the Jiankou section. Meanwhile, a new team of 463 local villagers has recently been hired to act as guardians of the Great Wall.

Great Wall tourism: Turning the poorest into the wealthiest

“Great Wall tourism gives the local community a tremendous push as it develops,” says Dong.

“Look at Mutianyu, a village at the foot of the Great Wall. It was once the poorest village in Huairou district. Some 30 years after it has tapped into Great Wall tourism, it’s now the wealthiest village.

“How did it go from the poorest to the wealthiest? It didn’t steal and sell a single brick from the Great Wall – what it sells is the culture of the Great Wall.

“We must develop local economies so the local farmers can enjoy the benefits and fruits of Great Wall preservation. Then you don’t even need to ask them to stop damaging the wall or stealing bricks – they just wouldn’t do it.”

Dong places his palm on the weathered wall, still contemplating it as he did 35 years younger. But today, he ruminates on a mission grander than his own journey.

“Someone, once upon a time, dug up some earth, molded it into a brick,” he says. “Someone else brought it all the way up the mountain and built a wall. Then many people guarded the wall for hundreds and thousands of years.

“The Great Wall is definitely alive. It isn’t just a cold, stone wall. When you put your palm on the wall, you’re holding hands with countless of ancestors from over the years.”