“You see all this? It now belongs to my family after decades of hard labor and sweat. We’ve redeemed it,” says Lorenzo Pacitti as he points to the hills surrounding his estate.

Pacitti is a rosy-cheeked shepherd, but not an ordinary one. He’s a billionaire, like all his colleagues who inhabit Comino Valley in Ciociaria, a virtually unknown misty patch of fluorescent green land stuck in central wild mountains of Italy.

Its name comes from cioce, the hairy sheep-leather shoes worn by herdsmen in the past. Ciociaria isn’t officially on a map, and is a secret even to most Italians.

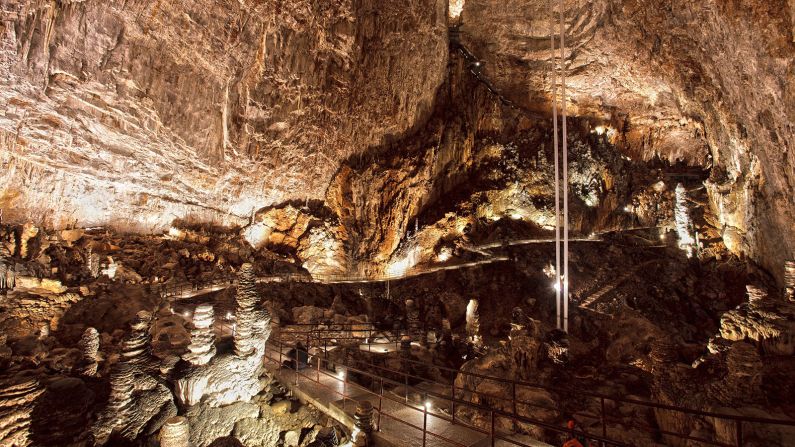

This is where skeletons of our early ancestors were found in deep caves, where the fiery Samnite tribes fought against the bloodthirsty Romans, and where the Gustav Line ran during World War II.

For centuries, it was a no-man’s kingdom at the boundaries of the rich papal state – a poor and outcast region roamed by bandits, saints and pilgrims. But today it’s enjoying a renaissance thanks to farmers, breeders and shepherds who’ve made a fortune with pigs, cured meats and mouthwatering cheeses.

They’ve opened rural resorts and gourmet restaurants. Their lavish villas dot the landscape amid medieval sanctuaries, healing fountains and pilgrimage sites rising from the ashes of pagan temples.

Sheep, goats and cows still cross the streets. Shepherds stop to say hello. But they’ve evolved, too. They don’t wear cioce anymore or go around snatching abandoned properties with large bundles of cash stuffed in their pockets.

Victorian cheese bistrot

Pacitti, who drives a sleek, green Kawasaki motorbike, is the owner of a pinkish Victorian-style villa called Casa Lawrence, where English writer D. H. Lawrence sojourned in 1919 to write his novel “The Lost Girl.”

Part of the mansion has been turned into a rustic cheesery, dubbed Caciosteria. There’s also a B&B featuring vintage furniture, Lawrence’s bed, chamberpot, bathtub, clothes, pajamas and writing table. There’s an eerie ambiance at the reading corner where the author loved to sit and meditate, taking in the bucolic view.

“The property passed into my ancestors’ hands because the owner, Lawrence’s British host, had no more heirs or couldn’t reach them. When he died my grandparents were already working on the land so it was easy for them to grab it,” Pacitti explains.

Pacitti makes one of the best sheep pecorino cheeses in Italy. It’s salty, crumbly and hard to bite with a thick outer skin. Best served with home-made fig and mulberry jam, the more seasoned it is, the tastier.

“It needs to stink of sheep,” adds Pacitti, who also owns the valley’s most prestigious dairy farm.

Another of his delicacies is Il Blu, which is a refined, pricey gorgonzola on the verge of having maggots in it, which sells at 45 euros per kilo (about $50).

At the Caciosteria, guests eat outside on wooden benches, surrounded by bull skulls hung on wooden doors to guard against ill omens. A final shot of ratafia liqueur with black cherries is the best digestif after a cheese-rich meal.

Casa Lawrence, C.da Serre Loc. Cervi, Picinisco, Frosinone; +39 0776688183

Foal carpaccio

Ciociaria is also home to a plethora of meat dishes.

In the nearby town of Picinisco, where Italy’s most dreaded bandit, Domenico Fuoco – akin to Robin Hood – once used his guns to persuade rich men to give their fortunes over to the poor, young cattle breeder Davide Gargaro has opened gourmet hostaria La Taverna di Arturo.

A strong stomach might be required, though it’s all a matter of overcoming stereotypes.

Extravagant dishes include baby horse carpaccio, horse salami, black pig lard (the many layers of fat make it tastier), pig cheek and neck salami, and dried sheep and goat meat sausages, known as “misischia,” which are traditionally stored underneath a horse’s saddle.

“The animal sweat keeps them warm, ready to eat,” says Davide, who loves his animals so much he leaves them to freely roam the hilltops and prefers to have someone else butcher them. “They’re my babies. How could I kill a six-month-old foal? I could never watch them die, but people who refuse to eat horse meat just because it’s a horse commit animal discrimination.”

The meat courses are paired with a fine red bottle of Caronte, named after another legendary village outlaw who loved to rob wine barriques from greedy merchants. The nickname also refers to Dante’s fiery old boatman Charon who transported sinners’ souls in the inferno of “The Divine Comedy.”

La Taverna di Arturo, Piazza E. Capocci, Picinisco; +39 3478314388

‘Faith is a mini-skirt’

Picinisco is at the crossroad of the so-called “triangle of faith” where folklore mingles with legends of miracles and holy apparitions of the Virgin Mary.

“Faith here is worn like a mini-skirt,” says the village priest Antonello Dionigi. “It must be tight at the center, short on the loose ends and holds the mystery of life right in the middle”.

And there are ghosts too. The town’s patron saint Lorenzo was said to have saved the city from Saracen invaders by creating a phantom army that chased the pirates away.

Rumor has it a group of Roman soldiers, dressed in armor and holding weapons, can be heard at night singing and partying beneath the ruins of a collapsed fortress.

The valley’s revival is also courtesy of immigrant families, who fled to Scotland and the New World in search of a better life and whose heirs have now returned to their native hometowns. And with big money to invest.

They have restyled old villages like Casalattico – an experimental mix of pink-yellow Victorian buildings, medieval alleys and Renaissance vaults.

Goat-dung spinach

A Scottish former lawyer, Cesidio Di Ciacca, has created a luxury resort in Picinisco, called Sotto le Stelle (Via Giustino Ferri, 1/7, Picinisco; +39 3466027120) inside an old abbot’s palace.

“I was looking for a place where many descendants of immigrants like myself can come back to and call home,” he says. “A point of reference.”

A private helicopter from Rome can take you there. The deluxe apartments’ panoramic balconies jut out of the ancient village walls, while the living-room arches were once open-air entrance doors for horse-drawn carts.

Early in the morning village grannies knock at the door and serve en-suite breakfast with tiny hand-woven baskets of fresh goat ricotta called “fusciella.” For lunch, the concierge treats guests to a dish of wild spinach called “orapi,” a supreme delicacy. It’s special and hard to find because it grows beneath goat dung which fertilizes it.

Bear-watching tours are organized in the national park.

Underground spoons

33 beautiful photos of Italy

Cesidio has even brought back from the grave his ancestors’ ghost hamlet and turned it into a thriving farm, I Ciacca (Via Giustino Ferri 7, Picinisco) where ancient Maturano white wine is made alongside extra virgin olive oil and transparent acacia honey.

He’s hired local young staff to boost the valley’s sleepy economy. Lush vegetation and moss covers rusty unhinged doors and dark rooms where bats have made their homes.

Everything seems frozen in time. You can still spot nails sticking out of ceilings where sausages were hung to dry. When Cesidio dug into the ground he discovered intriguing artifacts such as an old medal of Our Lady of Sorrows and a spoon belonging to Cesidio’s grandfather.

“My family has lived here since the 1500s. I want to give this place a second life,” he says.

“Each week fresh bread and pizza is made in the same oven where my grandmother baked and during summer we gather for picnics. My dream is to open a school of agronomy excellence.”

Want to avoid crowds in Italy? Consider the region of Molise

Wonder Ways: 5 hiking routes out of Rome

10 things Italy does better than anywhere else

Silvia Marchetti is a Rome-based freelance reporter. She writes about finance, economics, travel and culture for a wide range of media including MNI News, Newsweek and The Guardian.