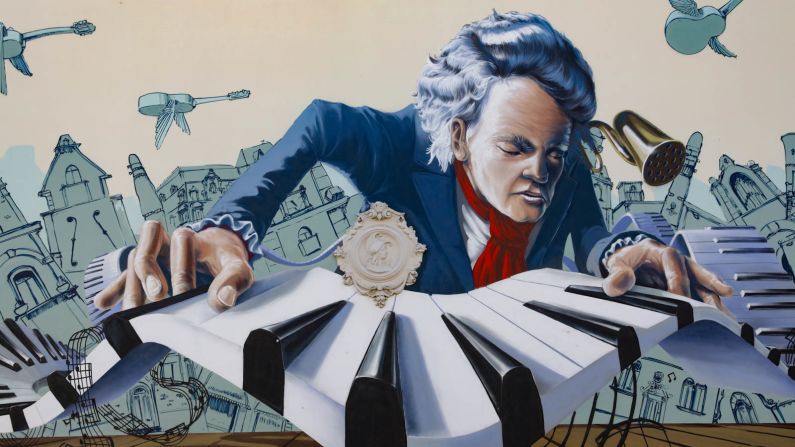

He’s the towering musical genius who didn’t let his deafness prevent him from becoming one of the world’s greatest composers.

Ludwig van Beethoven may have been born 250 years ago, but his story of achieving musical greatness despite his disability feels like a thoroughly modern story.

And with the 250th anniversary of his birth coming up next month – he was baptized December 17, 1770 – his hometown of Bonn is gearing up to celebrate.

That’s nothing new to Bonn. The city – which has a 2,000 year history and was the capital of West Germany from 1949 to 1990 – has hosted the annual Beethovenfest, an international festival of classical music, since 1844 (though this year’s edition was canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were among the guests of the inaugural edition – held just 17 years after the composer’s death – together with Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV and natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt. As well as attending the festival, they witnessed the unveiling of the Beethoven monument, which stands on Münsterplatz, a pretty city-center square, to this day.

Place of pilgrimage

There’s more than a statue, though. Bonn is determined to keep the memory of Beethoven and his work alive, and traces of the composer can be found around the city and the surrounding area.

Beethoven’s birthplace, originally built around 1700, has survived the ravages of time and is one of the few remaining old houses of Bonn. The small building with its pink baroque facade still stands at Bonngasse 20. Born in one of the attic rooms, Ludwig was named after his Dutch grandfather Ludwig van Beethoven, who was musical director at the court of Cologne’s Elector – one of the highest positions in the Holy Roman Empire.

He was the second of seven children of Johann – a court musician, and singing and piano teacher – and Maria Magdalena. But only three of them – all boys – survived infancy.

The Beethovens moved house in 1774, but none of their other Bonn homes have survived, making the birthplace a place of pilgrimage for music lovers.

It was turned into a museum in 1893, and came through both World Wars almost unscathed. During World War II the collection was evacuated, and the bombing of Bonn in October 1944 only saw minor damage to the house.

The museum was last modernized in 2017, and today – having encompassed the houses on either side of the birthplace, too – it houses a permanent exhibition on the life of the man and his family, as well as the largest collection of Beethoven memorabilia – from his possessions and his music to original paintings and letters – in the world.

The neighboring buildings house the Beethoven archive, a library and publishing house, as well as an award-winning chamber music hall.

But it’s the low ceilings, creaking stairs and wooden floors of Bonngasse 20 that convey an idea of the humble beginnings of one of the greatest musical artists of all time.

Beethoven-Haus Museum, Bonngasse 20, Bonn, Germany; +49 228 9817525

‘King forest’

One of the places that Ludwig and his family might have escaped to from the cramped conditions in the city center are the walking trails of the Kottenforst, the 4,000-hectare forest south of Bonn.

This is one of the oldest forests of the region and existed well before Beethoven’s time. A document from 973 CE calls it the “king forest,” and the trails that criss-cross it date back to the 18th century, established by Clemens August, Cologne’s Elector and the boss of Beethoven’s father.

August used the Kottenforst as his personal hunting ground and the forest still contains a hunter’s cottage from 1740 that was used as a relay station for fresh horses for the hunts. Today, though, the Kottenforst forms is part of the large Rhineland Nature Park. It’s still a perfect place to visit to experience “waldeinsamkeit” – essentially “forest solitude” – the act of escaping to the woods for some connection with nature.

Bare-chested Beethoven

As Bonn’s largest city park, the Rheinaue, on the banks of the Rhine, is the modern version of the Kottenforst – somewhere for locals to relax. In Beethoven’s time, it was an alluvial forest, but dwindled when the river was rerouted in the 18th and 19th centuries, and was later drained entirely and given over to agricultural use.

By 1949, when Bonn was named West Germany’s capital, it was one of the last natural spaces in the city, although a new government quarter was built on the northern edge of the Rheinaue.

To save it from more development, Bonn picked the Rheinaue as the location of West Germany’s 1979 National Horticultural Show.

The country’s biggest landscaping project of the time saw the 160 hectare area transformed into a park, creating gently rolling hills dotted with flower beds, many different trees and kilometers of winding footpaths – all without fences so citizens could experience the flowers and plants as they wanted.

Today, it’s home to another Beethoven monument – this one a 1938 granite sculpture by Peter Breuer. Moved here in 1995, it shows a hunky young Ludwig reclining bare-chested, overlooking the park’s small lake.

Eighth wonder

The wooded hills of the Siebengebirge, or “Seven Mountains,” rising on the eastern bank of the Rhine across from Bonn would have been a familiar sight to Beethoven.

At 460 meters (over 1,500 feet) Ölberg is the highest spot. Despite the name, this is actually an area of more than 40 hills – long-dead volcanoes, thought to be around 20 million years old.

However, the name prefers to take its lead from a local legend. The story goes that seven giants arrived to widen the Rhine, and then stuck their spades in the ground as they rested near Königswinter, 8 miles south of Bonn. The earth that crumbled off the tools became the Siebengebirge.

Artists and nature lovers have long adored the area. Eighteenth-century naturalist Alexander von Humboldt was so taken by the forested summits and craggy rocks of these “high mountains on a small scale” that he described them as the “eighth wonder of the world.”

The stone ridges were quarried by Celts, Romans and medieval Germans building churches and castles. Today, most of these quarries have grown over and in 1958 the area was designated the Naturpark Siebengebirge, North Rhine-Westphalia’s first nature park.

Back to Beethoven. The composer was so taken with the Siebengebirge that he would cross the Rhine to walk and dream here, as locals told French composer Hector Berlioz who visited for the first Beethovenfest in 1845.

Today there is a walking trail dedicated to the composer, with stops including the Drachenfels, or Dragon’s Rock.

This craggy rock crowned with the romantic ruins of a 12th-century castle has long been tied to myth, and has inspired artists and writers including Lord Byron and Heinrich Heine, as well as Beethoven. From here, there’s an enthralling view of the mythical hills and the panorama across the Eifel and Westerwald mountains.

Rhineland roots

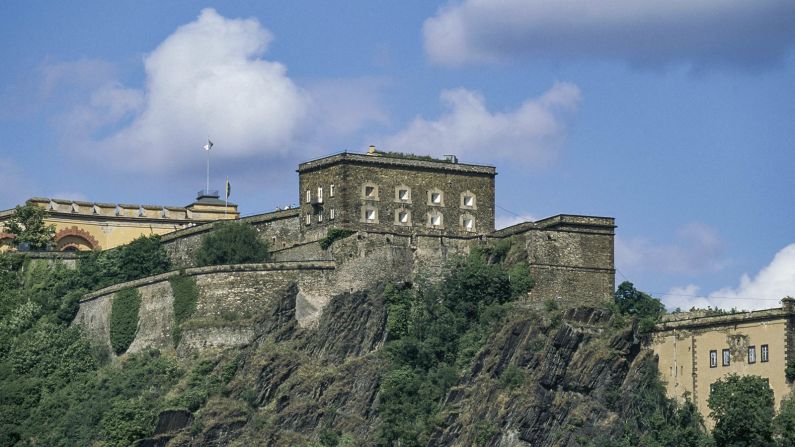

South of Bonn and the Siebengebirge is a fitting final stop for an exploration of Beethoven’s Rhineland roots. His mother was born in Koblenz, an hour south-east of Bonn.

The third largest city in the area, where the Rhine and Moselle rivers meet, Koblenz also has a 2,000-year history.

Maria Magdalena Keverich, as she was then, was born in 1746 in Ehrenbreitstein, the oldest part of the city.

It sits at the foot of the high bluff of the same name, which is topped by a fortress. There’s been one here since Roman times, though the one that can be seen today is Prussian, from 1828.

Koblenz’s top draw is the Deutsches Eck, or German Corner – an open headland overlooking the point where the two rivers merge. It’s home to a statue of Emperor William I., the so-called “founder of the German Reich”, on horseback. Put there in 1897, it was removed after World War II but but reinstalled in 1993 and re-dedicated to German reunification.

Maria Keverich, of course, had more humble origins. She was born to Anna Klara and Johann Heinrich Keverich, the head cook at nearby Philippsburg Castle.

Having married young, she was widowed at the age of just 18, and met her second husband through court violinist Johann Konrad Rovantini, who had married one of her cousins. She and Johann van Beethoven married in 1767, and Maria died at 40, in Bonn, of tuberculosis.

Her birthplace – one of Koblenz’s oldest buildings – is known as the Mother Beethoven House museum and is dedicated to the life of this strong woman and, of course, her genius son.

Mutter Beethoven-Haus, Wambachstrasse 204, Koblenz, Germany; +49 261 9730669