“Germany’s history is pretty unique,” says Ciarán Fahey. “I don’t think you have the same level of waste and destruction in other countries in Europe.”

Irish-born Fahey is the photojournalist behind Abandoned Berlin – a popular website turned coffee table book of the same name.

Fahey is passionate about exploring the German capital’s discarded buildings – hunting out the memories lurking behind the city’s crumbling walls.

Becoming a time traveler

“I was always into photography – because I work as a journalist, I guess I have this natural curiosity,” Fahey tells CNN Travel. “But it started for me really in 2009, with this abandoned amusement park Spreepark, not far from the city center in Berlin.”

Spreepark is a haunting shell of a theme park – once an East Berlin entertainment spot, it opened its doors in 1969 in honor of the 20th birthday of the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, as East Germany was officially known. Closed in 2002, it’s now an eerie, forgotten space.

Disused, nightmarish roller coasters are submerged in overgrown weeds, dinosaurs sculptures lie fallen on the ground and a broken Ferris wheel looms over this eery landscape. The attractions were abandoned when the park closed its doors and left to rot.

“My girlfriend at the time was from East Germany,” explains Fahey. “And she had told me that this fairground which she had visited as a kid was all closed up and abandoned, nobody was allowed to go in there, nobody dared go in there.”

Fahey was intrigued – he couldn’t help wondering what was behind Spreepark’s closed doors.

“It took a while, but eventually I got up enough courage to go in,” he says. “I went in on my own because I couldn’t get anyone to come with me. And it was just such a magical experience that when I got home I had to write about it.”

After Spreepark, Fahey began hunting out other other forgotten places in the German metropolis.

“It kind of all happened by accident, one place lead to another,” he says. “I just kept finding more and more and more, and that’s when I decided to put them all together on their own site, a dedicated abandoned site. That’s when things really took off.”

MORE: Abandoned castles around the world

Into the past

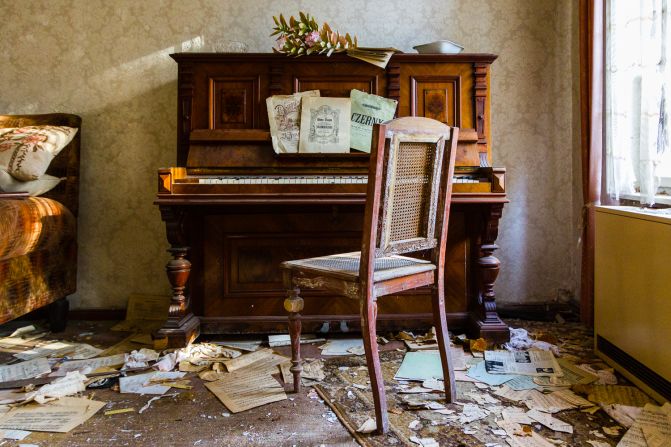

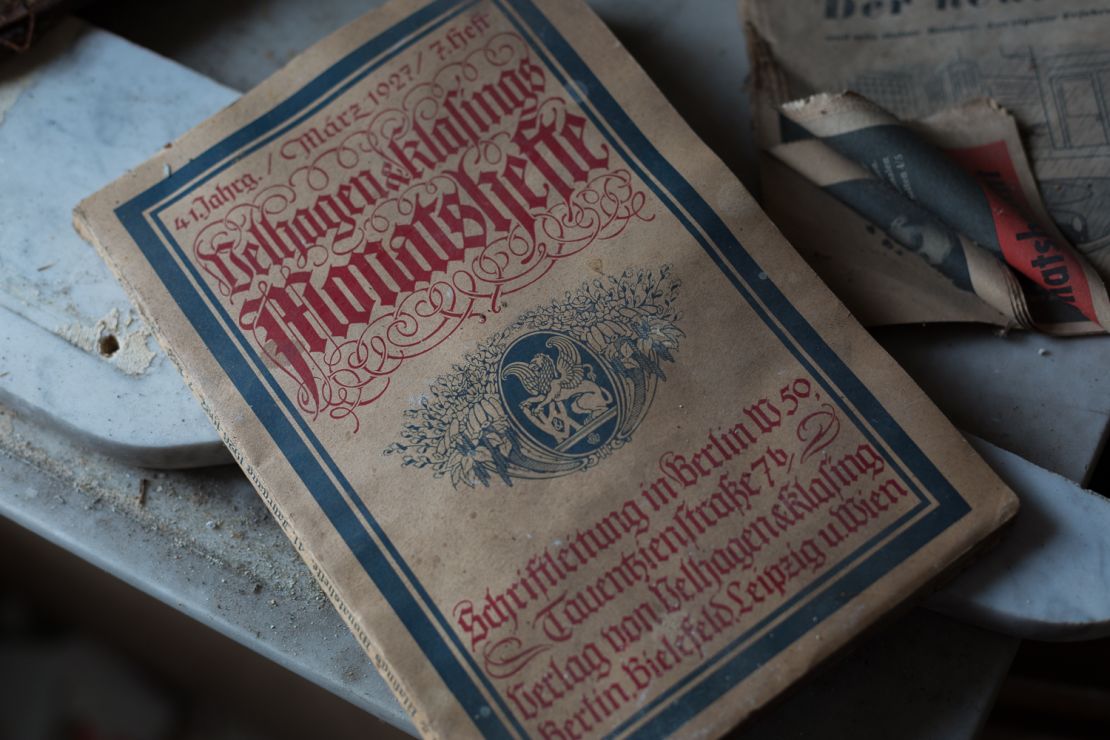

Fahey’s photographs are haunting snapshots – through his questioning lens, the echoing corridors of a former military headquarters or the moth-eaten corners of a 1920s magazine are eerily brought to life.

But it’s Fahey’s commitment to chronicling the stories behind the photographs that makes his venture a success.

“It would be a lot quicker just to go a place, take a load of photos and then publish the photos and forget about it,” he says. “But for me the most important thing is actually the stories behind it.”

Most of the places Fahey visits were abandoned within the past 30 years.

“I’d say 90% are since the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he says.

This means information can usually be tracked down online and in newspaper archives.

“There are usually newspaper articles about it, about factories closing down or hospitals closing or moving off somewhere else, you can find a lot of information through the local newspapers,” he says.

MORE: Visiting Berlin? Insiders share tips

Urban explorer

Visiting abandoned spaces allows Fahey to piece together the puzzles of the past. But breaking into an abandoned building is not as easy as it sounds – after all, it can be a crime. It’s also pretty dangerous and not recommended for the casual tourist.

On his website, Fahey offers his tips on circumventing guards, but he says ease of access changes over time, and varies from site to site.

“It really depends on each place,” he says. “Let’s say, for example, if it’s an old asylum or something, I’ll go round the whole perimeter of the site, just to check it out and see if I spot any broken windows, or any open windows, or any way in at all.”

Fahey says he’s had a few moments where he’s nearly been caught – or caught out.

“I remember one place I was getting into was incredibly difficult,” he recalls. “I noticed a gap above the door, a window that was slightly ajar. I managed to climb up over onto railings and get in over the door, squeeze in over the door – but it was really, really tight […] Eventually I dropped in the other side and I was inside the building, but then I had the problem of how I was going to get out again, because that was kind of a worry!”

Fahey made it – but he said there have been some close calls.

MORE: 11 things Germany does better than anywhere else

Decades of upheaval

At time of writing, Fahey says there are at least 90 abandoned Berlin buildings that he’s aware of, but has yet to visit. So why are there are so many in the city?

“Germany is very careless with its buildings,” says Fahey. “It just seems to go through them like other people go through a bag of crisps, it’s just like they’re consumed and then discarded.”

Germany has a political history characterized by upheaval and radical change. During the 20th century, buildings were erected and abandoned cyclically as one system of government was overhauled and replaced by another.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, many former East Berlin businesses went bust and buildings were abandoned.

“There were so many businesses closed down after reunification,” says Fahey. “Germany hasn’t really caught up yet with that, it hasn’t really made use of those buildings.”

Nevertheless, times are changing.

“Berlin always had this reputation of not having any money, being broke all the time, but there is much more money now and much more investment going on,” says Fahey. “The gaps are being filled in all the time. Old buildings are being taken over again.”

Even Spreepark looks like it might get another lease of life – the city bought the park in 2014 and there are rumors of refurbishment.

MORE: Best day trips from Berlin

Traumatic history

Whilst many relics of the former GDR are scattered across East Berlin, there are fewer abandoned Nazi-era buildings still standing.

“The city was pretty much flattened in the war, not a lot really survived,” says Fahey.

The fate of the former Third Reich buildings that remain in Berlin is a contentious issue.

Some advocate pulling them down, to prevent them becoming shrines. Others say they should be preserved as a warning from history for future generations.

“Personally I would rather [Nazi-era buildings] were preserved as artifacts,” says Fahey. “I think Germany generally does a good job, I think – it doesn’t just wipe the slate clean and pretend that nothing happened – it does highlight.”

Some buildings from this period have been left to crumble – such as a former sanatorium, Heilstätten Hohenlychen, which Fahey visited in a town north of Berlin. Horrific experiments were conducted here on concentration camp inmates.

On his first visit, Fahey knew nothing about the building’s terrible history.

“There’s no plaque or anything, there’s nothing outside to say these horrible things happened here,” he says.

“I only found about it while I was writing about it […] It was really chilling then, when I started digging into the story behind it to learn what had actually happened there. That’s maybe why it’s important to preserve them.”

Broadening horizons

Fahey’s urban exploration of Berlin is now the subject of a new book, published by Berlin-based publishers be.bra verlag.

“I was a bit unsure at first […] because every time you go into these places and take a picture, it’s evidence of a crime and that you’re trespassing on someone’s private property,” Fahey admits.

But once the publishers confirmed that they’d take care of any legalities, Fahey was on board.

He’s delighted that the book has opened up his work to German speakers for the first time.

As his work becomes ever more popular, Fahey has considered expanding his horizons away from his adopted city.

“But there’s way too much here to occupy me for the moment before I think of expanding it or going abroad or anything like that,” he says.

“It’s very much Berlin-based, Berlin and the surrounding area. So I’m going to concentrate on that for now. There’s still so much here that I haven’t written about.”