Editor’s Note: CNN International will air an inside look at the Yayoi Kusama show as part of its New Year’s Eve Live special on December 31.

Advanced age and the pandemic have done little to deter Japan’s Yayoi Kusama. At 93, the world’s best-selling living female artist is still painting daily at the psychiatric hospital she voluntarily checked into and has lived in since the 1970s.

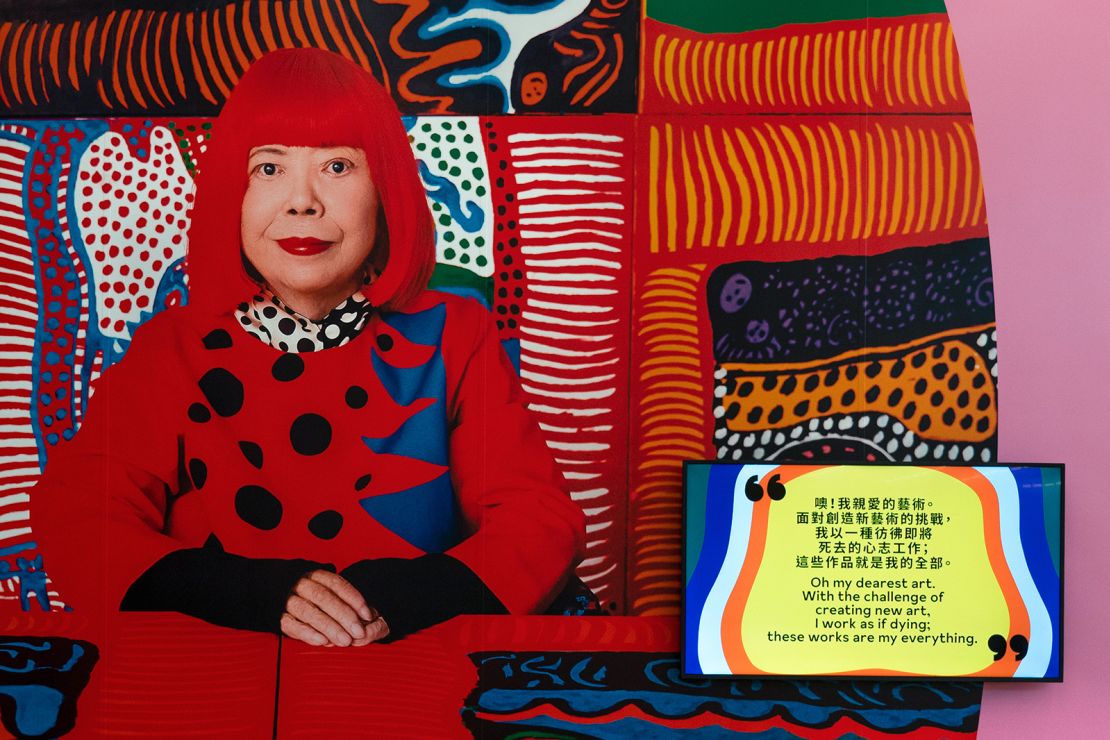

Some of her latest creations feature alongside early drawings in a new exhibition at Hong Kong’s M+ museum. Bringing together more than 200 works, “Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to now” spans seven decades as the largest retrospective of her art in Asia outside her home country.

Best known for her signature pumpkin sculptures and polka-dot paintings, which can command millions of dollars at auction, Kusama’s success has skyrocketed in the past decade. The most photogenic parts of her oeuvre — including her immersive “Infinity Mirror Room” installations, tickets for which sell out at museums the world over — have achieved mainstream appeal in the era of social media.

Needless to say, her new Hong Kong exhibition is filled with Instagram-friendly moments. But the museum’s deputy director Doryun Chong, who co-curated the show, says he hopes visitors take the opportunity to dive deeper.

“Kusama is so much more than pumpkin sculptures and polka-dot patterns,” he explained. “She is a thinker of deep philosophy — a ground-breaking figure who has really revealed so much about herself, her vulnerability (and) her struggles as the source of inspiration for her art.”

Infinity and beyond

Arranged chronologically and thematically, the show explores concepts that Kusama has revisited across multiple mediums over the course of her career. The notion of infinity, for example, appears in the form of repetitious motifs inspired by the vivid hallucinations experienced in childhood, when she would see everything around her consumed by seemingly endless patterns.

Visitors are given a sense of how these forms have evolved, beginning in a room filled with her “Infinity Net” paintings — including a breakthrough work she created after seeing the Pacific Ocean for the very first time from a plane window when she moved to the US from Japan in 1957.

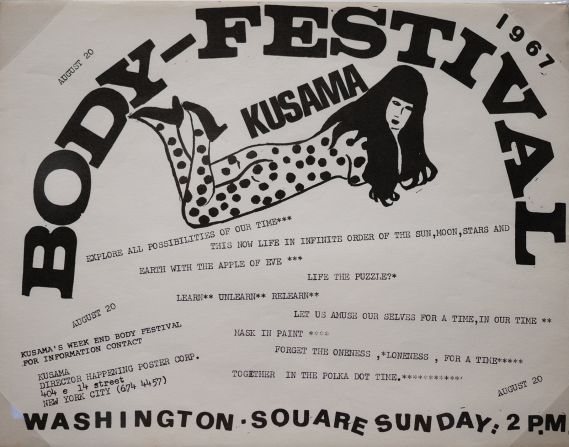

These nets appear again in “Self-Obliteration,” an installation created between 1966 and 1974, a period after Kusama established herself in New York’s male-dominated art world despite the discrimination she faced as a woman, and a Japanese one at that. (She believed male peers like Andy Warhol copied her ideas without credit). Comprised of six mannequins stood around a dinner table, every inch of the sculpture — from the human figures down to the furniture and cutlery — is covered with little looping brushstrokes.

More than 200 works brought together for major Yayoi Kusama retrospective

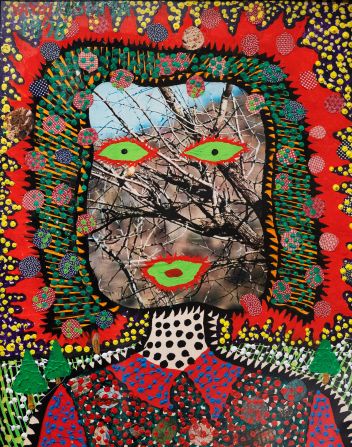

The motif later re-emerges to bold, vibrant effect, filling the bodies of amoeba-like forms in selected works from “My Eternal Soul,” a hundreds-strong series of acrylic paintings that she began in 2009 and completed last year. They appear in the retrospective’s colorful “Force of Life” section, which immediately follows one titled “Death,” a contrast that speaks both to the dichotomies of Kusama’s work and the internal struggles underpinning it.

“Nowadays we’re very used to (people) talking about their mental health challenges, but this was 60 to 70 years ago that she started doing this,” said Chong. “It really runs throughout her life and career, but it never really stays in a dark place. She always proves that, by talking about death and even her suicidal thoughts and illness, she reaffirms and regenerates her will to live.”

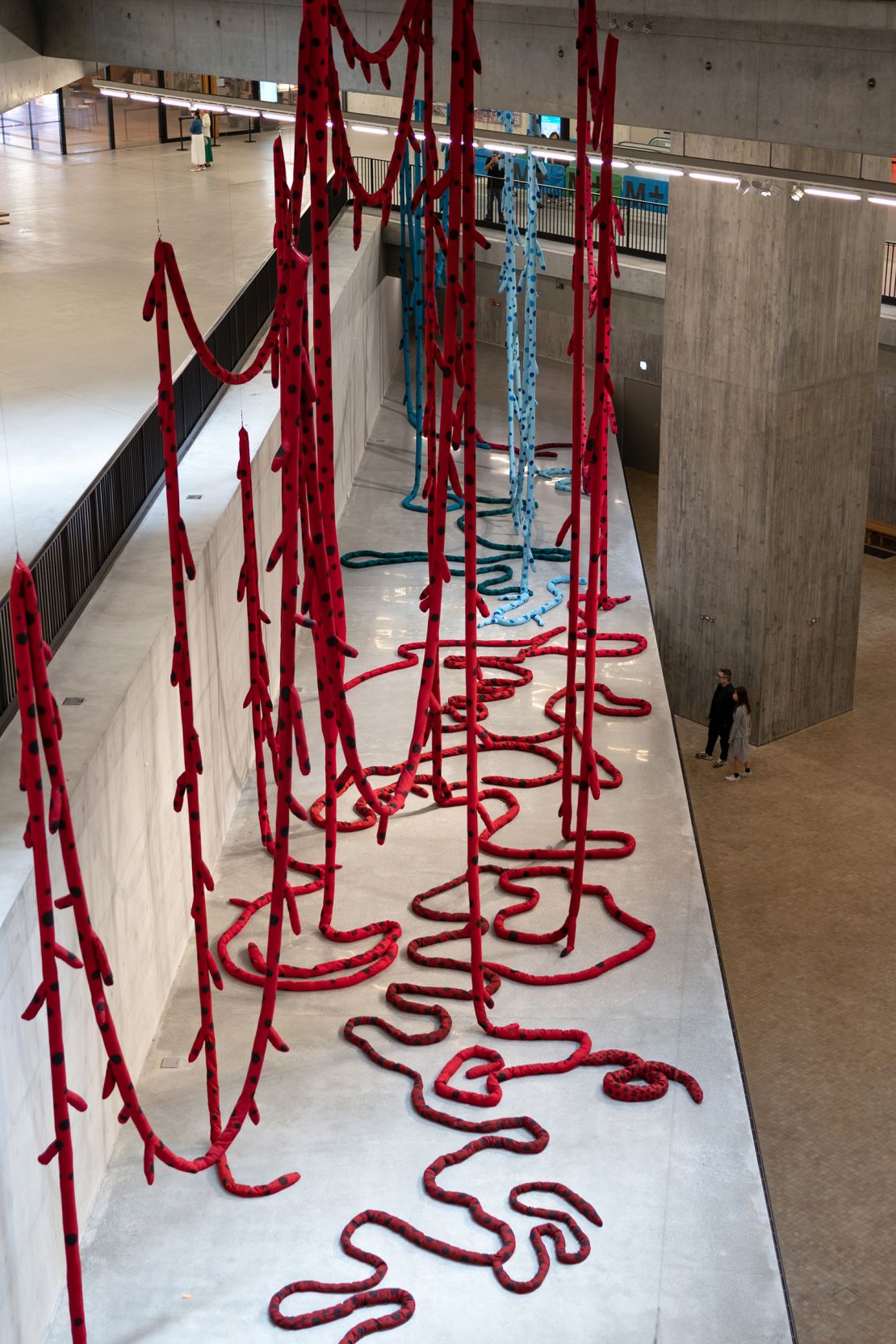

Elsewhere, the exhibition features lesser-known pieces from the artist’s repertoire, shining a light on what she created mid-career, when she returned to Japan depressed and disillusioned. Among them is a black and white stuffed fabric sculpture from 1976 called “Death of a Nerve.”

A 2022 version of the artwork, created for M+ and slightly renamed “Death of Nerves,” is also on display. Realized to a much grander scale and rendered in color, it embodies a sense of resilience and even optimism in contrast to the original. An accompanying poem acknowledges that, after a suicide attempt, her nerves were left “dead and shredded.” After some time, however, a “universal love” began “coursing through my entire body,” she wrote; the revived nerves “burst into beautifully vibrant colors… stretching to the infinitude of eternity.”

“It’s an unusual piece for Kusama because most people associate her with the pumpkins, or the mirror rooms, or with more Pop forms, but this is a very soft sculpture that she has always been working on, since the beginning,” explained Mika Yoshitake, an independent curator who worked on the M+ show with Chong, as well as previous Kusama shows at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. and the New York Botanical Garden.

“I think she’s incredible to be able to sustain her strength through art,” added Yoshitake, who last saw Kusama in 2018, before the pandemic. “She’s determined to have her story told.”

Small by comparison is a group of 11 paintings the artist began in 2021 and completed this summer, called “Every Day I Pray for Love.”

“She has always said ‘love forever,’ said Yoshitake. She wants people to be at peace, and have this warmth and to care for each other. There’s so much strife and war, terrorism, a lot of things she sees in the world, especially through this pandemic.”

In a short email interview with CNN, Kusama explained her dedication to her art.

“I paint every day,” she said. “I am going to continue creating a world in awe of life, embracing all the messages of love, peace and universe.”

Since her teens, Kusama has read Chinese poems and literature “with deep respect,” she said. As such, she added, she is “happy” to have her work on show in Hong Kong.

According to M+, the exhibition has now been described as “the most comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s work to date,” by curator and critic Akira Tatehata, who serves as director of the Yayoi Kusama Museum in Tokyo. Tatehata, who visited the museum in November, has long supported the artist, and was the commissioner of her solo representation of Japan at the Venice Biennale in 1993.

Art’s healing power

The retrospective also carries special meaning for M+, which used the show to mark its one-year anniversary.

Since its conception over a decade ago, the museum has been touted as Asia’s answer to the London’s Tate Modern or New York’s Museum of Modern Art. When it finally opened last year, it faced unique challenges, from Hong Kong’s changing political environment, which continues to raise censorship concerns across sectors including the arts, to pandemic restrictions that closed the museum for three months and, until recently, barred most international visitors from the city. But Chong sees the latter, at least, as “a blessing in disguise.”

“For a global museum to have opened and be embraced by our local audiences, first and foremost, in its first year couldn’t have been a better way to start the museum,” he said.

Recently welcoming its 2-millionth visitor, M+ hopes that eased Covid restrictions will allow more people from abroad to see its vast collection, which includes the largest trove of Chinese contemporary art, and the Kusama exhibition, which runs through May.

“(Kusama is) living proof that art is indeed therapy and has a powerful healing power,” said Chong. “And that’s such an important lesson, especially for us during this period of post-pandemic.”

Tom Booth, Kevin Broad, Noemi Cassanelli and Momo Moussa contributed to this story.