The history of the ancient world abounds with stories of all-powerful women. Take Nefertiti, the 18th-dynasty Egyptian queen who established a new religion and kickstarted a cultural revolution as the wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten; or Zenobia, a third-century warrior queen of Palmyra, who conquered Egypt and defied the Roman Empire.

But perhaps the most legendary of all is Cleopatra. The final ruler of Egypt’s Ptolemaic dynasty, she used her political tact, personal connections and endless capacity for reinvention to become the sole woman of the ancient world to rule alone.

And yet, more than 2000 years after Cleopatra’s death, the popular narrative around her life remains markedly one-dimensional. To many, she is the femme fatale who seduced two Roman statesman, and allegedly killed herself with the bite of an asp.

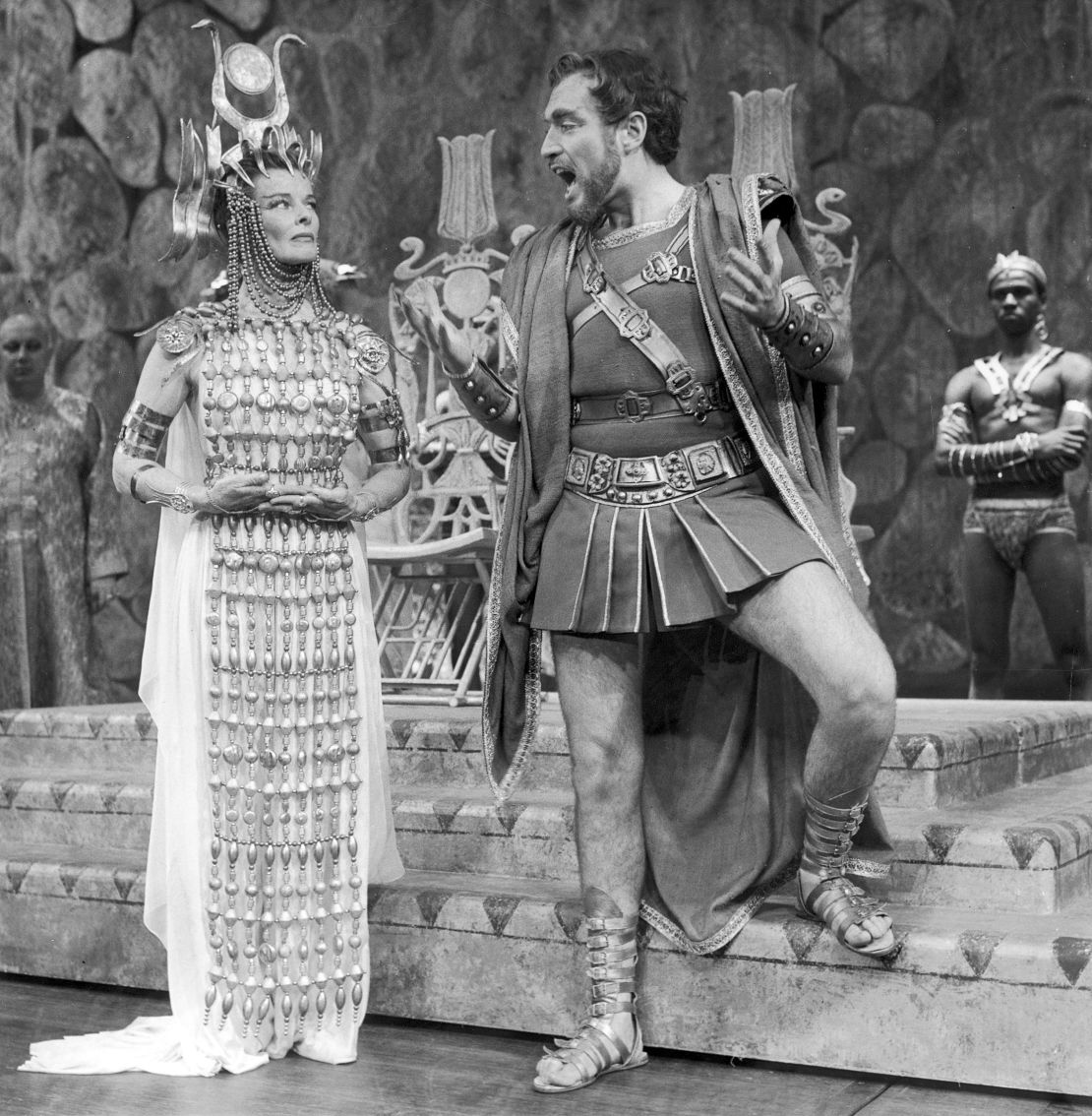

Her most remarkable asset, it seems, was her fabled beauty – a conception driven by cultural touchstones such as Shakespeare’s great tragedy “Antony and Cleopatra,” and Elizabeth Taylor’s iconic turn in the 1963 epic “Cleopatra,” which spawned the ubiquitous image of a queen with beaded braids, kohl-rimmed eyes and serpentine accessories.

But whether or not Cleopatra was beautiful (there is little primary evidence to give an accurate representation of her appearance), we know that, in the ancient world, what made her so formidable wasn’t her appearance or famous lovers, but the way she skillfully manipulated her public image to consolidate her power.

Master charmer

To this day, Cleopatra’s identity remains a subject of debate. Historical opinion is divided about her heritage, with the majority asserting her Macedonian Greek roots (she was a descendant of the Macedonian general Ptolemy), while others suggest at least partial African ancestry.

But regardless of her racial background, Cleopatra defined herself as an Egyptian queen, and was the first in the Greek-speaking Ptolemaic line to learn Egyptian. Intelligent, competent and charismatic, she was well-loved among her people – so much so that three centuries after her death, she was still worshiped in Egypt.

Cleopatra, however, didn’t simply embrace cultural norms: she reinvented them to her advantage. As British archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley observed in her 2008 book “Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt,” she “drew on the iconography and cultural references of earlier queens to reinforce her position,” dressing herself as the mother goddess Isis at ceremonial events to emphasize her divine right to rule.

Her personality was just as vibrant. In “The Life of Antony,” the philosopher-biographer Plutarch wrote of the “irresistible charm” of her conversation, and noted that “her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse… had something stimulating about it.”

Political strategist

When you consider Cleopatra’s longstanding reign, however, it is obvious that there is more at play than her vivacity. In ancient Egypt, foreign and familial ambitions upon the crown were a constant threat, and Cleopatra was astute at resisting both by forging connections to the most powerful Romans of the period. In 49 BC, she fled to Syria to assemble an army after being driven from Egypt by the advisers of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, her brother-husband and co-ruler.

Sometime after her return to Egypt in a bid to claim the throne as hers alone, Cleopatra managed to gain a private audience with Julius Caesar, who had traveled to Alexandria to settle the dispute. According to legend, she asked her servant Apollodoros to smuggle her into the palace wrapped in bed linen, gaining direct access to the Roman general. After successfully pleading her case, she gained both Caesar’s support and his affections, enabling her to overthrow her brother and gain sole possession of the throne. Within months she fell pregnant, and in 47 BC, her carefully crafted union produced a son and heir: Caesarion.

Following Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, Cleopatra out-maneuvered any of her other siblings’ potential designs on her position in ruthless dynastic form. Her younger brother Ptolemy XIV mysteriously disappeared (Tyldesley contends that he was almost certainly murdered), while her sister Arsinoe IV was eliminated by Marc Antony’s assassins at her behest, clearing the path for her to install Caesarion beside her as co-regent.

When Marc Antony was later appointed ruler of Rome’s eastern provinces, Cleopatra was quick to secure the next political alliance – and, in true form, she did so with theatrical flair.

In 41 BC, she journeyed to Tarsus, in what is now Turkey, at Antony’s invitation, dressed as Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, on a golden boat adorned with purple sails and silver oars. The dramatic stagecraft paid off, and the pair embarked on a passionate love affair that enabled Cleopatra to consolidate her grip on the throne and maintain Egypt’s independence. Over the years, the union produced three children, and by 34 BC, the monarch had cleverly assigned kingdoms to all of her children beyond Egypt in a bid to expand her empire.

Reframing the past

Despite Cleopatra’s impressive reign over two decades, it was to be the queen’s public image – one of the most important means of sustaining her vast empire against the rising power of Rome – that would thwart her in the afterlife. Following her death, Roman propaganda circulated by Octavian (the future Roman emperor Augustus I) – Mark Antony’s rival and eventual successor – cast the queen as a beautiful, scheming temptress to justify the conflict. This distortion, upheld by classical male authors, has endured for centuries, and continues to flourish in popular culture.

But perception seems to be slowly shifting. In recent years, a number of leading authorities on Cleopatra, including Tyldesley and Egyptologist Joann Fletcher, have been working to dismantle the myth, foregrounding new research and overlooked details to add the monarch’s accomplishments back into the picture. And with Gal Gadot set to star in an upcoming film that reorients Cleopatra’s story “through women’s eyes,” a more nuanced representation could be coming to the big screen.

As Cleopatra continues to captivate the public’s imagination, it’s more important than ever that we begin to think more critically about the ancient queen, not least because what we know of her achievements and the real fiber of her character is arguably far more compelling. If we relinquish our fixation on aesthetic value and look at the unbiased evidence from her own era, we stand to gain a far richer understanding of Cleopatra, as well as other women leaders from classical antiquity – one that will inspire as much as fascinate us today.