In 1937, a young trucker named Malcolm McLean was delivering a load of cotton to a harbor in Hoboken, New Jersey. As he watched workers slowly transport the boxes by hand onto a ship, the story goes, he thought there had to be a better way to do it.

It turns out, there was: a big metal box that could be detached from the truck transporting it, and put on a ship. And about 20 years after first envisaging it, McLean was ready to show his invention to the world. He loaded a former war tanker with 58 “trailer vans,” as The New York Times called them in 1956, and set off to change history.

Little did McLean know that the intermodal container, as it would later be called, would not only revolutionize trade by decimating the cost of shipping, but it would also find a second life through architecture.

Becoming a thing

Affordable, sturdy and obviously, easy to transport, containers found an alternative use outside of shipping ports in the 1960s as portable showcases for trade fairs. But the first indication that someone wanted to make a “habitable building” out of one came from a 1987 patent application. Seven years later, futurist guru Stuart Brand of the counterculture magazine Whole Earth Catalog added to their profile with his book “How Buildings Learn,” which he wrote in a converted container.

But the father of modern container architecture, or “cargotecture,” is American architect Adam Kalkin, whose work in the field spans luxury homes in the US to orphanages in South Africa.

“Containers are mostly being used in architecture as low cost widgets in an iterative process,” Kalkin said in an email. “That is OK, necessary and important. But the results are predictably pedestrian. We do projects that are fun for us.”

This sense of fun is evident in his Push Button House, a fully furnished room in a container that pops open using hydraulics – which debuted at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

Kalkin’s 2003 project, 12 Container House, is still often cited as one of the most elegant and functional examples of container architecture. Since then, he says, things have changed.

“It has become a thing, so now you don’t have to overcome as much disbelief when you work with people,” he said. “Every project is another opportunity to define the future of containerized architecture. Right now we are splicing hard core environmentalism with super nerdy technology.”

Affordable chic

The make-it-up-as-you-go nature of container architecture has made heroes of those who got it right early on. Among them is Peter DeMaria and his 2006 Redondo Beach House, the first two-story container structure to comply with the National Building Code in earthquake-prone Southern California.

The home was designed to combine heavy gauge steel and high-quality materials, while still being affordable. “We consistently posed the question, ‘what can a home be?’ as opposed of being mired in ‘what has a home been?’” DeMaria said in an email interview.

“It spearheaded a whole movement in the architecture world and we’re witnessing the impact today with the multitude of projects utilizing up-cycled shipping containers.”

Containers, he said, are cheap, ubiquitous and resistant to many of the threats buildings usually face, such as fire, mold, termites. Most importantly, they’re already fabricated.

“All too often creatives look to reinvent the wheel but we’re already surrounded by innovative solutions in non-architecture related industries,” DeMaria said.

The wow factor

Container homes are varied in style and cost. Some are affordable, configurable and eco-conscious, such as the prefab ones made by Wisconsin-based Mods International. The company sells a fully ready, no-frills, 160-foot container home on Amazon for $23,000.

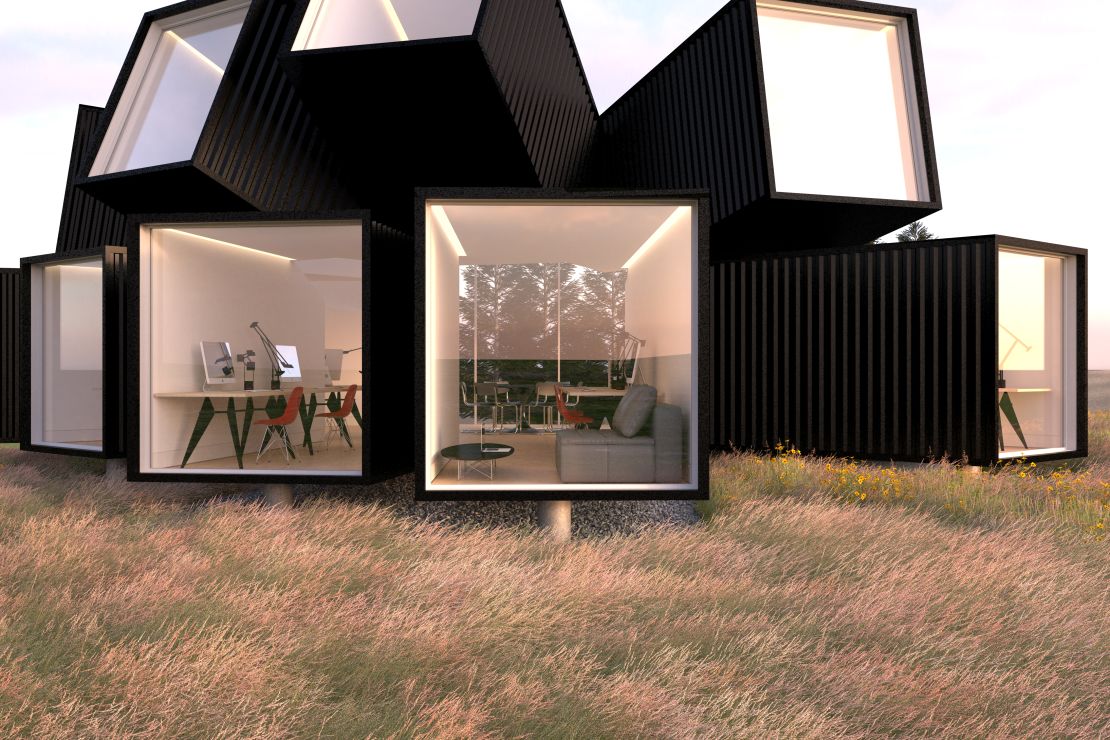

Others go straight for the wow factor, such as the Joshua Tree Residence, a 2,100-square-foot house made from white containers bursting out from a central point, to be built in 2018 just outside California’s Joshua Tree National Park.

James Whitaker, the London architect who designed it, thinks containers offer an enjoyable challenge. “You’re given a very standard, strict module to work with, and you have to make it interesting. They’re essentially the width of a bed, so it’s challenging to see what interesting spaces you can create when you give yourself such a limitation,” he said in a phone interview.

Pushing the envelope

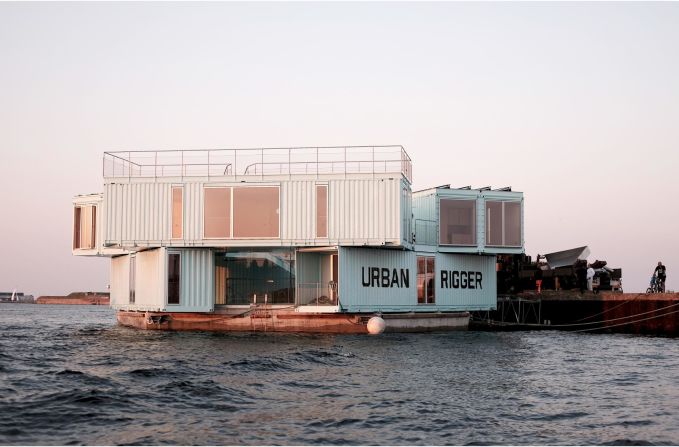

Containers remain a popular choice for emergency or temporary accommodation and student housing (a recent notable example is Bjarke Ingels’ Urban Rigger in Copenhagen), as well as retail units, schools, greenhouses, and even swimming pools.

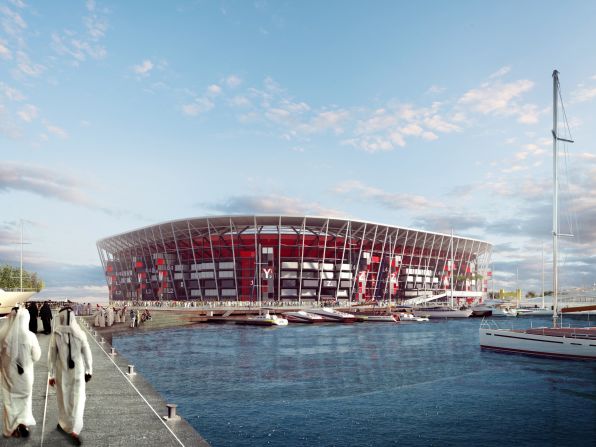

But how about a whole stadium? Madrid’s Fenwick Iribarren Architects plans to build one of the 2022 FIFA World Cup venues in Qatar from around 1,000 containers.

Not only would this cost half as much as a regular stadium, they claim, but once the tournament is over, the whole structure could be dismantled and shipped elsewhere. “It’s the perfect legacy solution,” said designer Mark Fenwick in a phone interview.

“Instead of leaving behind a dilapidated area, after the event 20 or 30 different smaller sports venues can be built elsewhere from this structure, and the original site can become a public park or space for real estate development.”

More outlandish proposals – which include one from 2015 involving a skyscraper – aren’t free from criticism. “There’s a school of purists that uses containers as a low-cost build module and other guys who use it mainly as an architectural deign element, because they like the industrial look of it,” said Roger Wade, the entrepreneur who built Boxpark, a 60-container retail park in London which he describes as the world’s first pop-up mall.

After using containers as a cheap alternative to bespoke stands in trade shows, Wade thought of using them for a retail store that could move to different locations, an idea inspired by the work of Adam Kalkin. Boxpark opened in London’s Shoreditch district in 2011. “In those days I had issues finding an architect that knew anything about container architecture, it was too early. People look at it now and think it’s obvious, but it wasn’t at the time,” he said.

But now, Wade argues, the popularity of containers is making some designers misunderstand their nature. “I use traditional containers and understand their limitations. Some designs out there have cantilevers and containers hanging off each other – these are not even containers, they’re made to look like them but they are bespoke structures that cost a fortune to make. That’s no longer about a low-cost form of building,” he said.

According to DeMaria, the evolution of container design has been like every other movement in architecture. “There are incredible projects and then there are ill-advised projects,” he said.

“A handful of architects have pushed the envelope with containers and the more these projects are built, the more creative the next generation of container based design will be.”