Since photography’s beginnings, practitioners around the world have been fascinated by the power of image series to convey meanings about identity.

Take Nigerian photographer J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, who in 1970 set out on a self-assigned photo project: to document the unique hairstyles of Nigerian women. Over the next four decades he took more than 1,000 dazzling photographs of intricate crowns and gravity-defying braids – what he called “sculptures for a day.”

Individually, each image is testament to beauty and has a specific cultural meaning. But as a series, Ojeikere’s work can be read as a greater story about post-colonial Nigeria, the changing hairstyles serving as metaphors for the its development and ambition while elegantly rebutting Western stereotypes.

Ojikere’s work is now one of many photo series recently on display at “Structures of Identity: Photography from The Walther Collection,” an exhibition at the AIPAD photography show earlier this year. Together, they posed the question: What can photo series reveal about the world – and our identities – that single photographs cannot?

Rejecting the art world’s tendency to focus on single images, Walther Collection curator Brian Wallis aimed to suggest “another way of looking at photography,” where the story is discovered within the structure of a how images are arranged together.

Early representation

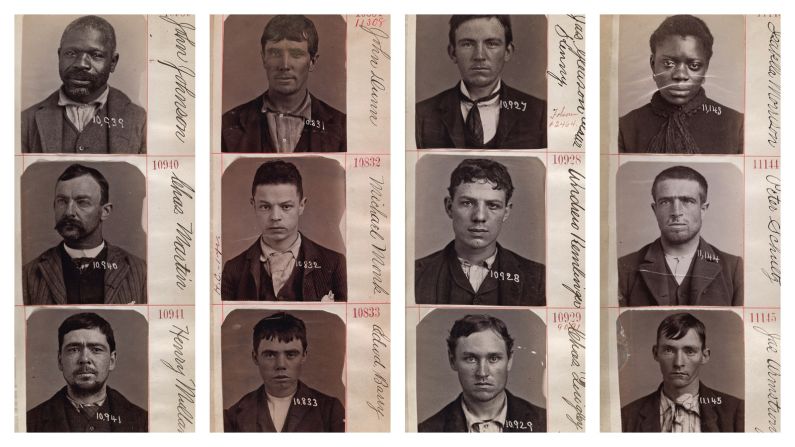

The oldest works in the Walther Collection include some of the first examples of photo series: mugshots. We may take these for granted today, but, as Wallis points out, they were a specific type of image developed in the 19th century so the state could categorize the physical attributes of convicted persons, and even make “predictions” about their criminal behavior.

“This is a way of cataloging a certain strata of society … to divide society into those that are acceptable and those that are not,” Wallis said.

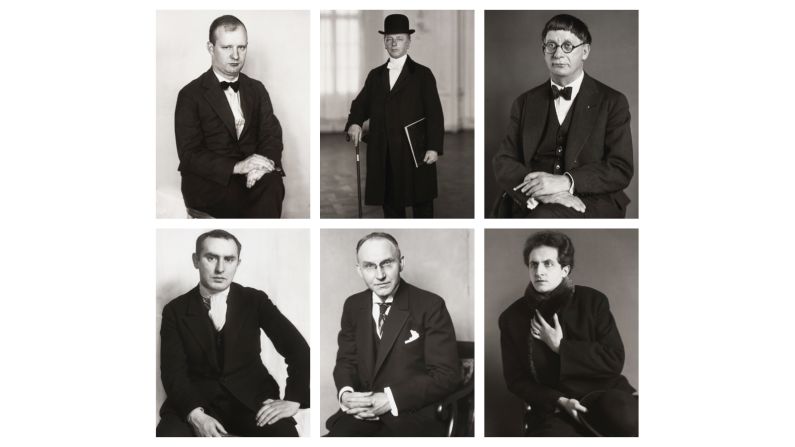

Another key work is that of German photographer August Sander, who embarked on an ambitious project to create objective portraits of all possible class and social backgrounds in 1920s Germany.

The idea was to put people all on the same level by photographing them in a studiously unsentimental way. Yet, as generations of critics have argued, what if the images merely reinforced categories of people rather than breaking them down?

“What’s interesting about Sander as a touchstone is he’s not really one or the other,” Wallis said. “You can take the very same picture, and find a very positive social statement or a very critical one, depending on how you look at it.”

Political portraits

In the 20th century, photographers used series in increasingly pointed ways to make statements about society.

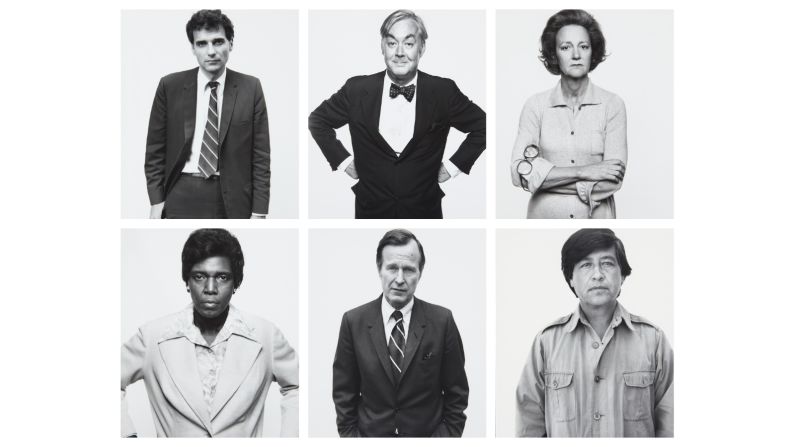

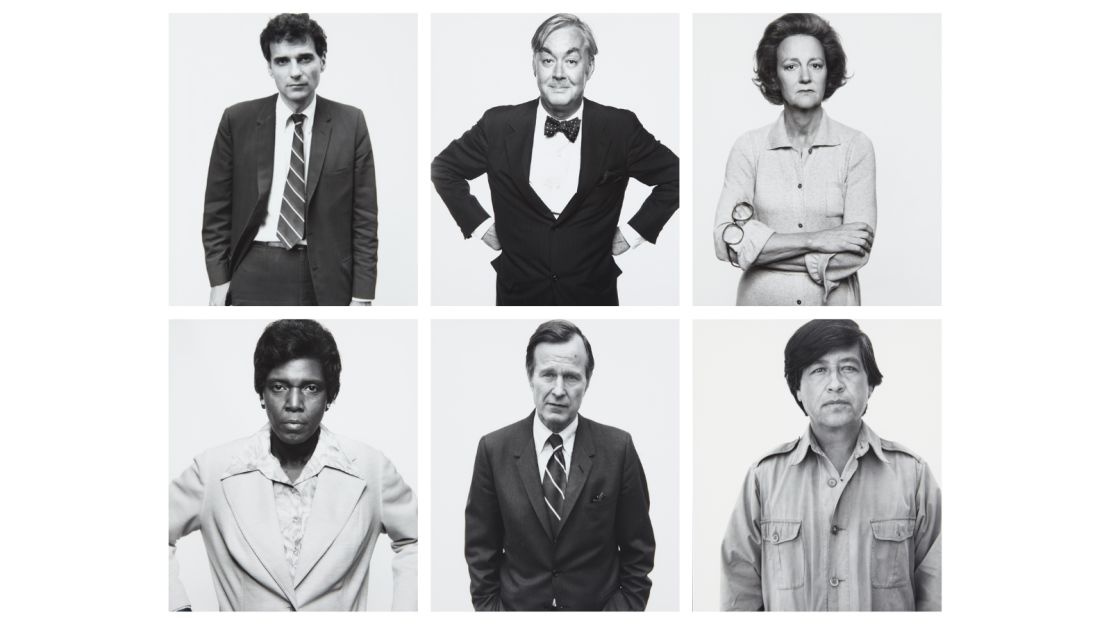

One example is Richard Avedon’s “The Family,” 69 portraits of America’s political establishment – from newspaper editors to presidents – shot informally against white backgrounds.

Avedon’s technique brought out each subject’s personality. He caught them in moments of seeming frankness. But when the series is considered as a whole, the artist’s political message becomes clear: these people make up the untouchable power structure of the United States.

This resonates with New York photographer Accra Shepp’s “Occupying Wall Street,” shot 31 years later. In a series of straightforward portraits, Shepp captured the inverse of Avedon’s “Family”: ordinary citizens-turned-protesters, gathered at Zucotti Park. And as Shepp’s subjects faced off against Avedon’s at the Walther Collection exhibition space, one suddenly got a visual sense for what inequality looks like.

This was taken a step further in one of the Collection’s most powerful series: Zanele Muholi’s intimate portraits of queer, lesbian and transgender South Africans, some of whom are survivors of physical and sexual violence.

With expressions that convey both vulnerability and dignity, Muholi’s subjects challenge society’s assumptions about them. Taken together, the photos turn shared oppression into an affirmation of collective strength: their visibility is transformed into a pointed political message.

Thinking visually

Whether in a web search or our social media feeds, we now encounter photo series daily, and interpret their social meanings as second nature.

“The internet has definitely made people more adept at using and reading pictures,” Wallis said. “The amount that is being dumped online … is a revolution in access, which inevitably expands your way of thinking about the world visually.”

Wallis’ hope is that people continue to think about photographic series critically, and use them as powerful ways to parse the world.

“I’m interested in what doesn’t make it into the museum,” he said. “It’s about making visible social histories that haven’t been made visible.”

Works in this article can be found in “The Order of Things: Photography from The Walther Collection,” published by Steidl.