Editor’s Note: Julia Nebrija is an urban planner based in Manila.

Saudi Arabia, Jesus Christ and Pokemon might make for an unlikely trio of design inspirations. But in the Philippines, don’t be surprised to find all three adorning the side of a jeepney.

An unofficial national symbol, the converted jeeps turned public transport staples are tapestries of Filipino life. But amid longstanding calls to modernize, the jeepney is on the verge of a major transformation.

The Duterte administration is demanding that any jeepneys in violation of updated regulations – including those built more than 15 years ago – are taken off the roads by Jan. 1, 2018. New rules on size, accessibility and engine quality could take thousands of vehicles out of service, as well as potentially endangering the livelihoods of drivers and others in the jeepney industry. The changes could also effectively mean the end of a Filipino design icon.

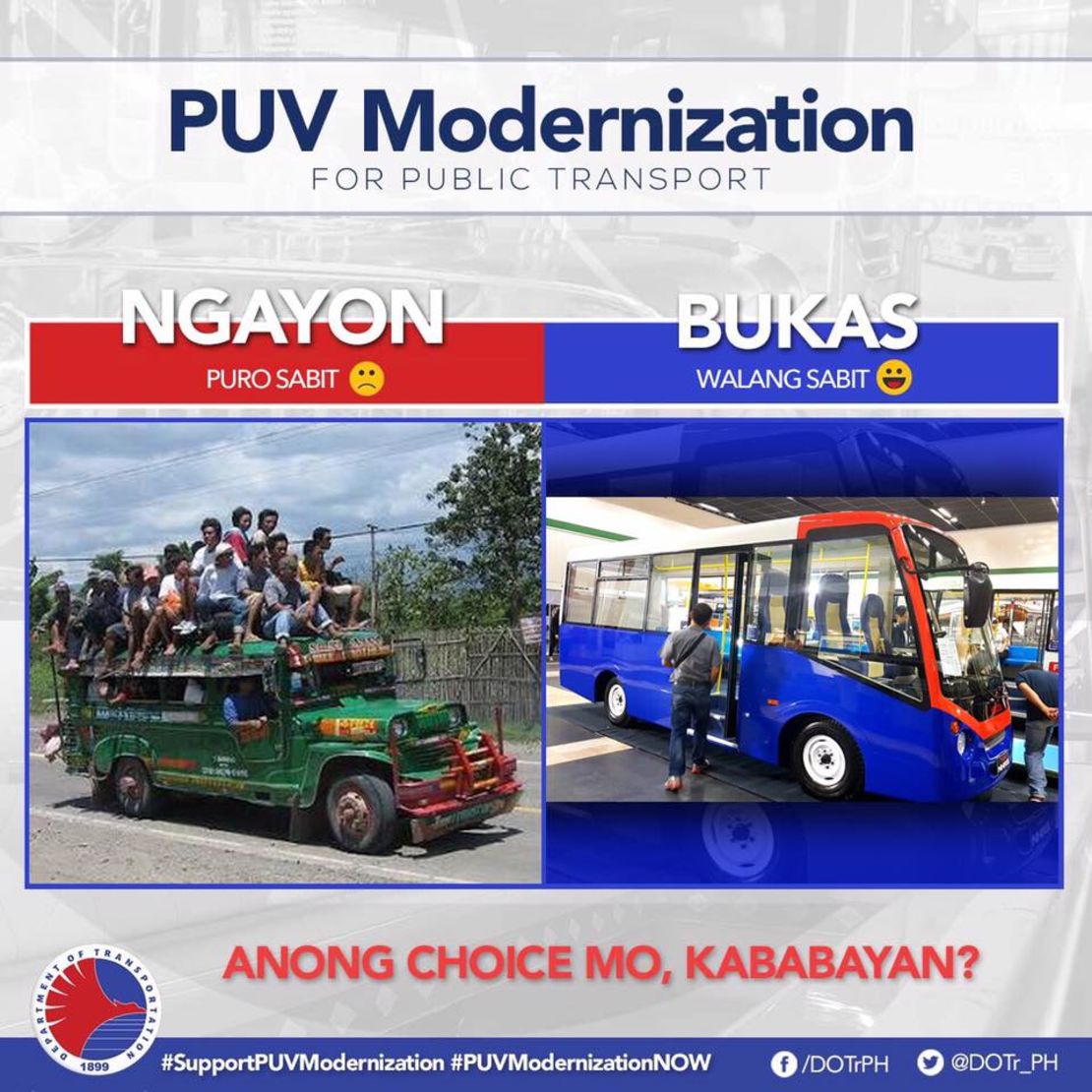

The sweeping changes have come as welcome news to many, however. Although the fleet reaches places where there is often no alternative, jeepneys contribute to pollution and crippling congestion in cities across the country. And while they are a visual feast of kitsch decoration, the vehicles are also notoriously challenging to board – especially for those with mobility difficulties.

So what will it take to reform a decades-old mode of transport that is entrenched not only in the daily lives of millions, but in the national psyche?

The ‘King of the Road’

Born in post-war Manila, the jeepney offered a new way to get around after the city’s street cable cars were destroyed by bombing. Local mechanics would fashion the vehicles from war jeeps abandoned by the Americans, customizing them to accommodate more passengers.

But what began as a makeshift solution to a temporary problem now serves almost 40% of transport users in Metro Manila and the surrounding provinces.

Today, official figures show that – even before counting unofficial vehicles – there are almost 180,000 franchised jeepneys on the country’s roads.

Costing just 8 pesos ($0.16) a ride – compared to 12 pesos for a bus ride or 15 pesos for a train – jeepneys provide an affordable alternative to Filipino commuters. In Metro Manila, which is home to 12 million people across 250 square miles, the vehicles’ size and shape allows them to navigate streets untouched by the limited public transit system.

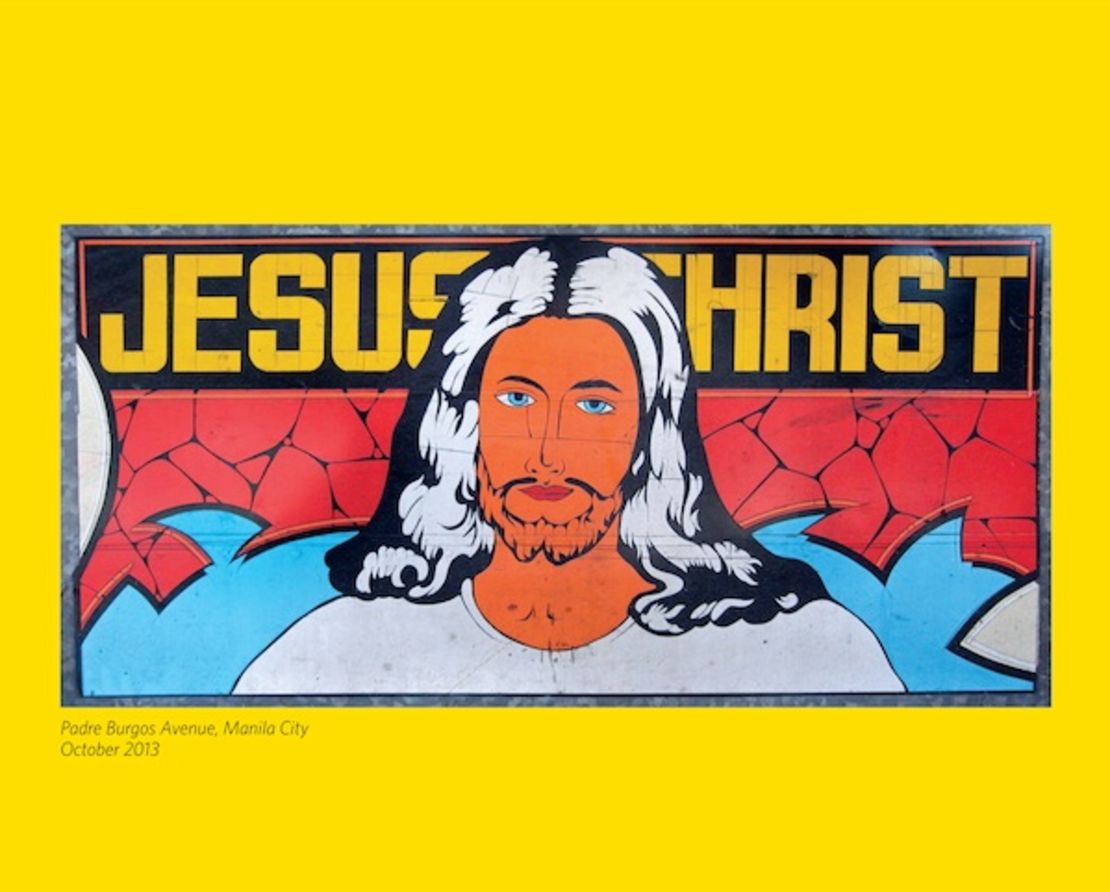

Known in the Philippines as the “King of the Road,” jeepneys are also renowned for having designs as loud as their roaring engines. Embracing a “more is better” philosophy, owners use vibrant colors and busy ornamentation to decorate their vehicles.

Jeepneys: 'King of the Road'

The body of each jeepney tells a story. An image of a cruise ship might represent overseas Filipino workers, who represent one in five of the world’s seamen. Pastoral scenes, beaches or mountains may signify the owner’s family heritage. Airbrushed basketball players and cartoons also make regular appearances.

Even if money is tight, few jeepney drivers will skimp on their elaborate name plates. Displayed at the front of the vehicles, they serve as a dedication to children, astrological signs and overseas countries where relatives live or work.

The jeepney can be seen as an extension of the home, according to Bru Sim-Nada, co-author of “Biyaheng Langit,” a book exploring the vehicles’ religious iconography as a genre of folk art. As well as providing welcome-mat-style messages to boarding passengers (such as “God Bless this Trip”), jeepney art is a source of personal pride for owners.

“It’s a basic need for people who don’t have money – who don’t have power – to establish a presence and a sense of belonging,” she said.

The jeepney has also become a staple image on souvenirs, from key chains and magnets to mugs and T-shirts. It is a true national symbol, according to Jowee Alviar, co-founder of graphic design firm Team Manila.

“The jeepney is unique to our visual culture, it represents the creativity, resilience and adaptability of the Filipino,” he said.

Modernization underway

Having previously mass-produced vehicles, the jeepney industry now mostly caters to custom orders. As such, the fleet largely consists of second-hand vehicles, propped up with scavenged parts and reliant on polluting diesel. This puts them at odds with President Duterte’s desire to modernize the country’s transportation system as part of a “golden age of infrastructure.”

Amid promises of new subways, bus lines and rail systems, the jeepney can still play a part in the country’s transport by offering feeder routes or “last mile” services. But the fleet may soon look drastically different.

A number of new prototypes unveiled at a car expo last month offered a peek at the jeepneys of the future. These updated models may help owners meet new requirements, but their look is a long way from the vehicles’ current, chaotic designs, said Ed Sarao, founder of jeepney manufacturers Sarao Motors.

“[The new vehicles] are definitely not jeepneys, all the lines and details are different,” he said, claiming that the new models should be called what they are – mini buses. Decorating a mini-bus in the style of a jeepney will “look awkward,” he added.

But if the new vehicles may lack the character of their predecessors, passengers like RR Realasa are more focused on the anticipated improvements.

“They will be bigger, more comfortable, safe,” said the 26-year-old, who uses a jeepney as part of his two-and-a-half-hour commute from Taguig to Manila.

In addition to a design overhaul, changes are also expected to routes and franchising in the coming years. The introduction of formal ticketing and drop-off points pose further challenges to the conventions of jeepney rides – currently, riders tap the roof to stop the vehicle, while fares passed up a line of passengers to the driver.

Having already embarked on a series of protests and strikes across the country, jeepney operators, drivers and “barkers” (the gruff attendants who canvas for riders) are expected to further resist to the changes.

A jeepney owner for 15 years, Efren Borela earns 2,500 pesos ($48) per day. He has invested his savings into his vehicle and is unsure if he can recover the investment and buy a new roadworthy one.

Authorities say that owners like Borela will be offered financing to help meet the cost of upgrades or new vehicles. And officials, including undersecretary for road transport at the Department of Transportation, Thomas Orbos, remain confident that reform will ultimately benefit everyone in the industry.

“I’m sure when people see [the new system] on the road, and once people try it, the opposition will be lost,” he said.

The jeepney does – and will continue to – represent the potential of re-invention. After all, images of horse-drawn carriages remain common in the vehicles’ decorations, referencing a type of mass transit now reserved for a tourist trip around historic areas. This may prove to be the fate of the brightly colored jeepney too. But as the sign on the rear of one Manila jeepney muses: “Forever is just a word. There’s no forever.”