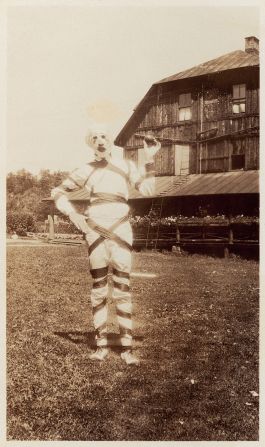

A black-and-white photo from the early 1900s shows a woman in rural America, her face covered with a sinister white mask. In another, from 1930, a tall figure stands in a field tightly wrapped in what looks like a white sheet and black tape, while a 1938 image shows three people driving to a party in hair-raising skull masks.

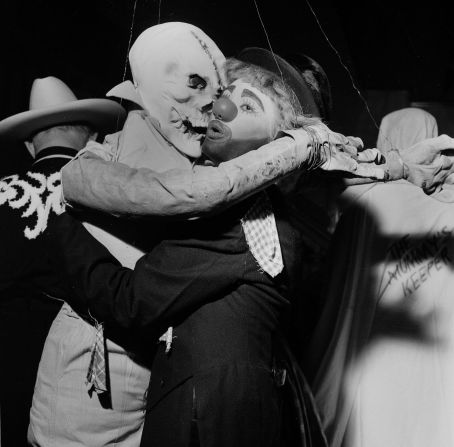

Halloween costumes from the first half of the 20th century were terrifying. Drawing on the holiday’s pagan and Christian roots – as a night to ward off evil spirits or reconcile with death, respectively – people often opted for more morbid, serious costumes than the pop culture-inspired ones of today, according to Lesley Bannatyne, an author who has written extensively about the history of Halloween.

“Before it evolved into the family-friendly, party occasion we know it as, October 31 was deeply linked to ghosts and superstitions,” she said in a phone interview. “It was seen as a day ‘outside of normal,’ when you act outside of society’s norms.

“Wearing ghoulish costumes – not horror-inspired like today’s, but plain frightful – was an essential part of it.”

Ancient roots

The genesis of Halloween costumes may date back over 2,000 years. Historians consider the Celtic pagan festival of Samhain, which marked summer’s end and the beginning of the year’s “darker” half in the British Isles, to be the holiday’s precursor.

It was believed that, during the festival, the world of the gods became visible to humans, resulting in supernatural mischief. Some people offered treats and food to the gods, while other wore disguises – such as animal skins and heads – so that wandering spirits might mistake them for one of their own.

“Hiding behind their costumes, villagers often played pranks on one another, but blamed the spirits,” Bannatyne said. “Masks and cover-ups came to be seen as means to get away with things. That’s continued throughout Halloween’s evolution.”

Christianity adopted October 31 as a holiday in the 11th century, as part of efforts to reframe pagan celebrations as its own. Indeed, the name “Halloween” derives from “All Hallows Eve,” or the day before All Saints’ Day (November 1). But many of the folkloristic aspects of Samhain were incorporated and passed on – costumes included.

In medieval England and Ireland, people would dress up in outfits symbolizing the souls of the dead, going from house to house to gather treats or spice-filled “soul cakes” on their behalf (a Christian custom known as “souling”). From the late 15th century, people started wearing spooky outfits to personify winter spirits or demons, and would recite verses, songs and folk plays in exchange for food (a practice known as “mumming”).

American influence

As the first wave of Irish and Scottish immigrants began arriving in the US in the 18th century, Halloween superstitions, traditions and costumes migrated with them.

Once Halloween entered American culture, its popularity quickly spread, according to fashion historian and director of New York University’s costume studies MA program, Nancy Deihl.

“People in rural America really embraced its pagan roots, and the idea of it as a dark occasion, centered around death,” she said in a phone interview. “They wore scary, frightening get-ups, which were made at home with whatever was on hand: sheets, makeup, improvised masks.

“Anonymity was a big part of the costumes,” she added. “The whole point of dressing up was to be completely in disguise.”

By the 1920s and 1930s, people were holding annual Halloween masquerades, aimed at both adults and children, at rented salons or family homes. Costume preparations sometimes began as early as August, according to Bannatyne. Falling right between summer and Christmas, the celebration also seemed to benefit from its timing in the calendar. “It was a way to come together before the turning of the season,” Deihl said. “Marketers played heavily on that as Halloween became more commercialized.”

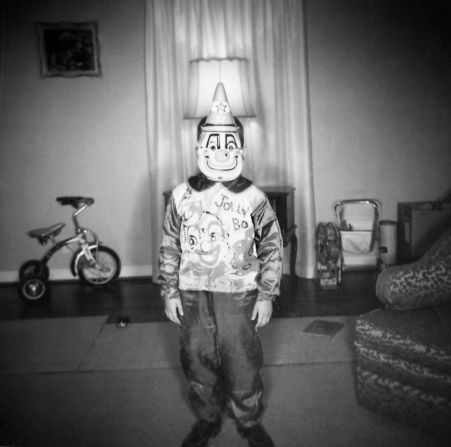

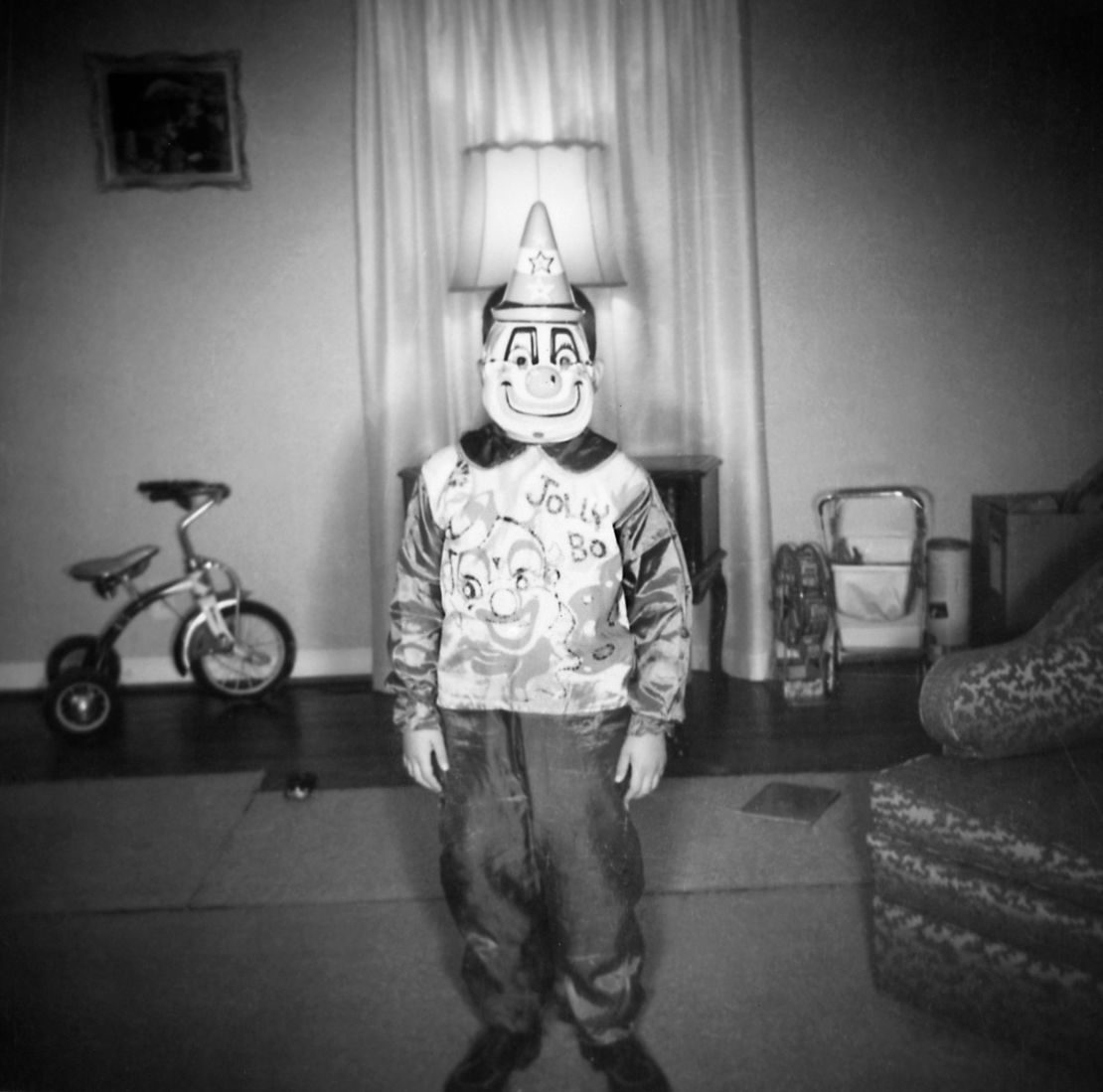

Those same decades also saw the emergence of costumes influenced by pop culture, alongside the first major costume manufacturing companies. The J. Halpern Company (better known as Halco) of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, began licensing images of fictional characters like Popeye, Olive Oyl, Little Orphan Annie and Mickey Mouse around this time, according to Bannatyne.

“People also became fascinated with impersonating characters at the fringe of society,” she said, adding that pirates, gypsies and even homeless people became common outfit choices.

Continuing the tradition of old practices like souling and mumming, Halloween pranks became a common phenomenon in North America – sometimes to the point of vandalism and rioting. By the mid-1940s, the press had dubbed the night’s anarchy (or its broken fences and smashed windows, at least) the “Halloween problem” – and costumes may have “partly enabled that behavior,” Bannatyne said.

In an effort to discourage criminal damage, local and national officials attempted to recast the holiday – and dressing up for it – as an activity for younger children. The Chicago City Council even voted in 1942 to abolish Halloween and establish “Conservation Day” on October 31 instead.

“Throughout its history, Halloween has gone through changes of ownership,” said Anna-Mari Almila, a sociology research fellow at the London College of Fashion, over the phone. “Its original connection to death became more and more tenuous, which made space for altogether different kinds of (costumes).”

After World War II, as TV brought pop culture into family homes, American Halloween costumes increasingly took after superheroes, comic characters and entertainment figures. They also became increasingly store-bought: By the 1960s, Ben Cooper, a manufacturing company that helped turn Halloween into a pop phenomenon, owned 70 to 80 percent of the Halloween costume market, according to Slate.

Dropping the mask

It was around this time that adults started dressing up for Halloween again, according to Deihl. Like kids’ costumes, their approach was often more fun than frightening – and would eventually be just as inspired by “Star Wars” or Indiana Jones than by demons or ghouls.

“Generally speaking, the ’60s marked a shift in the way we dress up for Halloween,” Deihl added. “Grown-ups, in particular, started ditching masks and full-on coverage, opting to show their faces. Costumes became a way to play a lighter, special version of oneself: showing the world you ‘were’ Wonder Woman, or Luke Skywalker, or what have you.”

But there was still a place for scary outfits, encouraged by a slew of splatter-horror movies that started emerging in the 1970s and 80s, from John Carpenter’s “Halloween” to Wes Craven’s “A Nightmare on Elm Street.” These decades also saw gay communities across the States adopt the holiday as an occasion to wear outrageous outfits and hold parades, contributing to a boom in Halloween parties and the popularization of provocative costumes that “in recent decades,” Deihl, said, “have oftentimes leaned towards the overtly sexy and campy.”

“Halloween costumes have gone from disguises to full-on exhibitionist,” Almila said. “Today, it’s one big capitalist celebration completely detached from any vestige of Christianity or paganism, and more centered around expressing people’s fantasies – which also explains its success globally.”

“I think they’ve certainly become more reflective of the times we live in,” Deihl added. “But there are also far fewer people making their own Halloween outfits now, and a lot less personal creativity going into what you wear, compared to the early days.

“We’re all drawing from the same range of costumes available for purchase. And creating immense waste because of it. I think people would express themselves much more individually if they crafted their own costumes like they used to.”

This article was originally published in October 2019.