Editor’s Note: Jonathan Chatwin is a writer, journalist and author of “Long Peace Street: A Walk in Modern China.”

When the American writer David Kidd arrived in Beijing in 1981, having not seen China’s capital for three decades, he found the city almost unrecognizable.

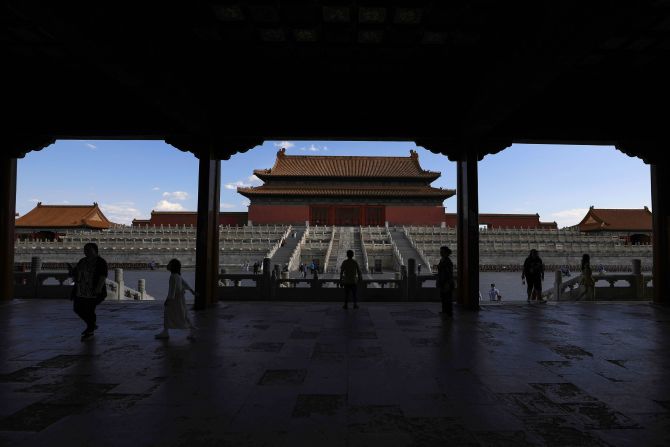

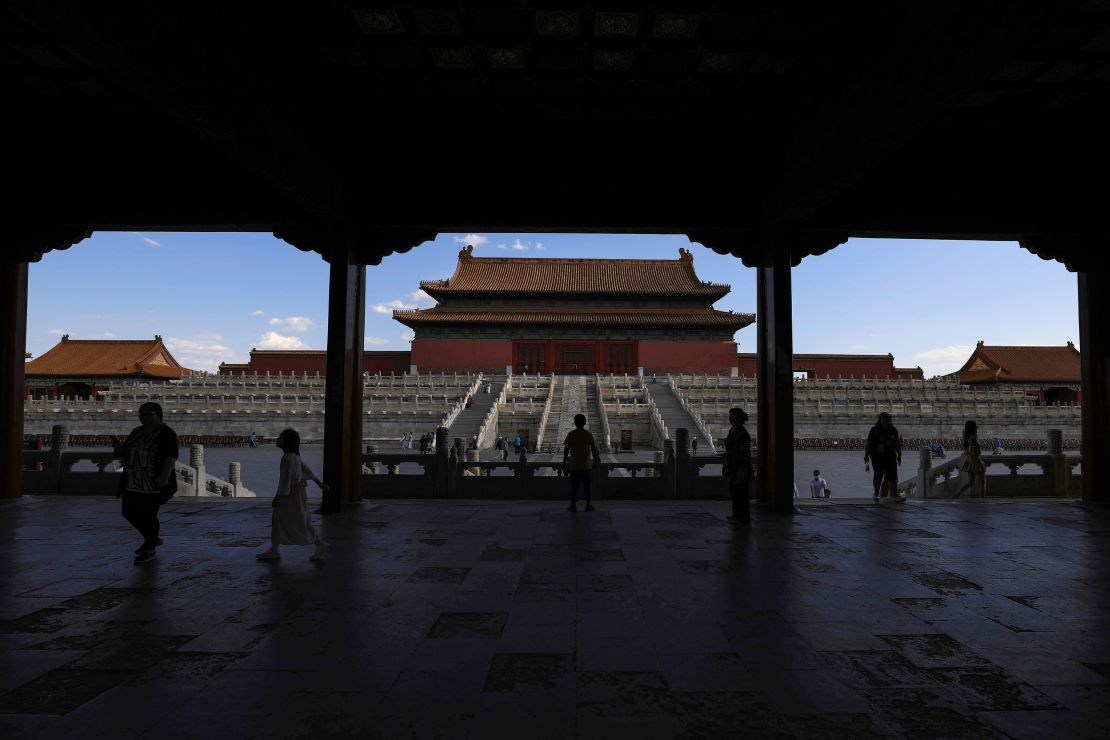

The fabled city walls were gone; its temples turned into schools and factories. Only in the vast imperial palace complex of the Forbidden City “could I imagine that the city surrounding it was unchanged,” Kidd wrote in his memoir “Peking Story.” It created the illusion, he added, “of supernatural space and time.”

The Forbidden City, which turns 600 this year, was carefully designed to conjure such an illusion.

It is the world’s largest palace complex, covering more than 7.75 million square feet (720,000 square meters) and separated from the rest of Beijing by a 171-foot-wide (52 meters) moat and a 33-foot-high (10 meters) wall, with gate towers guarding its entrances. The fortress-like design was intended to protect the emperor, but also to emphasize his pre-eminence: The emperor was, after all, heaven’s representative on Earth and, in its scale, majesty and separateness, his palace was built to ensure that neither his subjects, nor foreign visitors, ever forgot that.

Despite its monumental scale and central importance in Chinese history, however, the Forbidden City’s continuing presence at the heart of the country’s capital has been a story of survival against the odds. Fires, wars and power struggles have all threatened the imperial complex during the last six centuries.

Even as recently as the mid-20th century, the fate of the Forbidden City looked far from secure. After taking control of China in 1949, the country’s communist rulers engaged in fierce debate over this vast area at the center of Beijing. Twenty-four emperors had taken the throne there over the course of the Ming and Qing dynasties, and the palace’s history and design made it an obvious symbol of the iniquities of feudal rule that the Chinese Communist Party had railed against, and an obstacle to its vision of a new socialist capital.

Yet the Forbidden City survived waves of drastic alterations made to Beijing’s architectural layout in the 1950s and 60s, in spite of Communist Party leader Mao Zedong’s disdain for old buildings and other remnants of China’s imperial past – as well as suggestions by others in the leadership that the palace should be turned into central government offices.

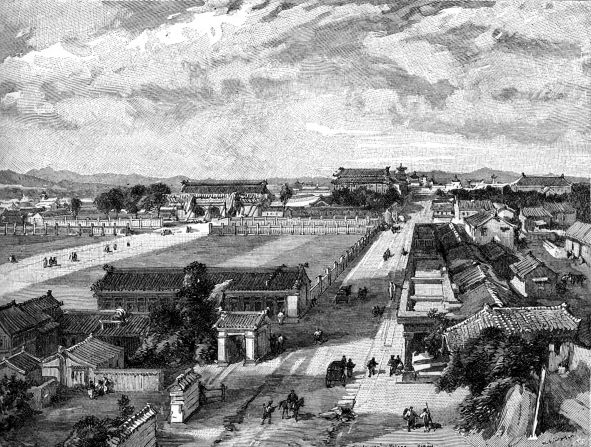

In these first decades of communist rule, Beijing’s centuries-old walls were pulled down to build an underground subway system, while historic ministries and imperial archives (in front of Tiananmen, or the “Gate of Heavenly Peace,” just to the south of the Forbidden City) were razed to lay a vast granite square. Between the square and the gate, old archways were torn down, and a broad highway was built in their place.

There is no single reason why the Forbidden City escaped this period of razing and rebuilding, though the cost of redeveloping such a sizable area, combined with the absence of a coherent plan for what would replace it, both played a role. But it was just the latest chapter in an unlikely tale of survival.

Ancient design principles

The Forbidden City is, today, synonymous with Beijing, but its story actually begins in a city almost 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) to its south: Nanjing. (“Jing” in Mandarin means “capital,” with Beijing translating as “northern capital” and Nanjing as “southern capital.”) In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty, designated Nanjing – a city on the Yangtze river, in the economic heartland of China – as the national capital, building a palace complex, ringed by a vast city wall, from which to rule.

It appeared that Nanjing would remain China’s capital for as long as the Ming were in charge, and when Zhu Yuanzhang died, his grandson and chosen successor continued to rule from the city. However, one of Zhu Yuanzhang’s sons, Zhu Di, who established a power base in Beijing, had other ideas. In the summer of 1402, after a three-year conflict between Zhu Di and the emperor, the imperial palace in Nanjing was razed by fire, apparently killing the emperor and his family. Zhu Di claimed the throne for himself, becoming known as the Yongle Emperor and establishing Beijing as the national capital.

There he built an imperial palace to dwarf that of his predecessor to the south. The Forbidden City, as it would later become known, was completed in 1420, and required a workforce of hundreds of thousands, using materials from across the country: precious timber from Sichuan in China’s far southwest; fine gold leaf from Suzhou, near Shanghai; clay bricks from Shandong to the east. Though the marble came from a quarry only 31 miles (50 kilometers) west of Beijing, some of the largest pieces were so heavy that they could only be transported during the winter, when water was poured onto the road to create an icy surface across which the stone could slide – when pulled by a team of thousands.

The Forbidden City’s original architects drew design principles from the second-century B.C. text, the “Rites of Zhou,” which had long informed ancient Chinese urban planning. Symmetry was crucial, with a city’s boundaries marked by a square wall. The text decreed that roads, starting from gates built into these walls, were to run east to west and north to south across the city. At the very center of the complex, protected by yet another wall, should sit the ruler’s palace.

Looking at maps of the square, walled inner-city of old Beijing, with the palace at its center, the influence of these ancient principles upon the Yongle Emperor’s architects are obvious.

Even the Forbidden City’s smallest design details are rich in symbolism, from its golden yellow tiles – a color linking the emperor to the sun – to the ceramic animals that line the corners of the palace roofs. The dragon stands for the emperor and the power invested in him, the phoenix signifies virtue and the seahorse brings good fortune. The palace walls and supporting columns were washed with red clay from Shandong province; again, a color associated with the emperor, who wrote his edicts in red ink.

Though emperors of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) added some new buildings and gardens, the layout of the palace has remained fundamentally the same since it was completed in 1420. Yet, as soon as construction finished, the Forbidden City was threatened by what would become a perpetual nemesis: fire.

The palace buildings, primarily made of wood, were vulnerable to lightning strikes, the open flames used for lighting and heating, and even pyrotechnic displays. To combat the risk of fire, hundreds of metal vats were placed around the palace to collect water (they were heated with small fires during the winter to stop the water freezing) and early lightning conductors were built onto higher roofs.

Still, there were regular fires, as well as earthquakes, over the centuries. As a result, almost all of the buildings of the Forbidden City are later reconstructions of the originals – the Hall of Supreme Harmony, for instance, has been rebuilt seven times since its first construction.

Decades of conflict

Conflict has also posed a regular threat to the Forbidden City. In 1644, most of the palace was destroyed at the hands of rebel leader Li Zicheng. After the Ming dynasty fell, Li occupied the city for 42 days, until he was forced out by the Manchu forces who would establish the next ruling dynasty, the Qing. As he left, his troops set fire to the palace compound, destroying most of its buildings. It would take decades for the Qing to finish the reconstruction work.

Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a series of domestic uprisings and foreign conflicts also threatened the Forbidden City, as the Qing began to lose their grip on the country. These culminated in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, and the most serious infringement to the sanctity of the Forbidden City in over 250 years.

The Boxers were an anti-foreign, anti-Christian sect who besieged Beijing’s foreign community for 55 days that summer. When international troops arrived to relieve the beleaguered international residents, the ruling Empress Dowager, who had supported the Boxers, fled with her court to Xi’an, more than 500 miles to Beijing’s southwest, leaving the palace empty. Its buildings had already been damaged by shelling, and some in the foreign community questioned whether it might be a good idea to burn the palace down altogether.

Forbidden City at 600: China's imperial palace through the years

Instead, in the absence of the imperial family, the diplomatic corps and the soldiers who had saved them took the opportunity to explore the sacred interior (the “Da Nei,” or Great Within, as it was known) of the resting court: an unprecedented infringement. Some were not above stealing the valuables left behind in the Empress’ hurry to escape. The court would return, chastened, in 1902 and the Qing dynasty limped on for another decade.

Though the last emperor, Puyi, abdicated in 1912, bringing to an end imperial rule in China, he would remain a resident in the Forbidden City’s resting court for another 12 years, an emperor in name only, whose authority reached only to the walls and gates of his living quarters. China’s new republican government meanwhile established itself in the lake palaces to the west, a complex known as Zhongnanhai, which is still home to today’s Communist Party leadership.

Conflict continued to pose a threat to the buildings of the imperial palace – and the treasures contained within. In 1917, in response to an attempt to restore Puyi as emperor, republican planes dropped bombs onto the palace during the first air raid in China’s history. Little damage was done, at least according to an account by one British diplomat, who wrote that the only casualties were some goldfish in a pool and a nearby eunuch who was injured in the blasts.

After Puyi was evicted by a warlord who took control of Beijing in 1924, the next phase of the palace’s storied history began. In 1925, it fully opened as a public museum (prior to that, only a small area of the palace had been open to visitors, who were not allowed access to the resting court).

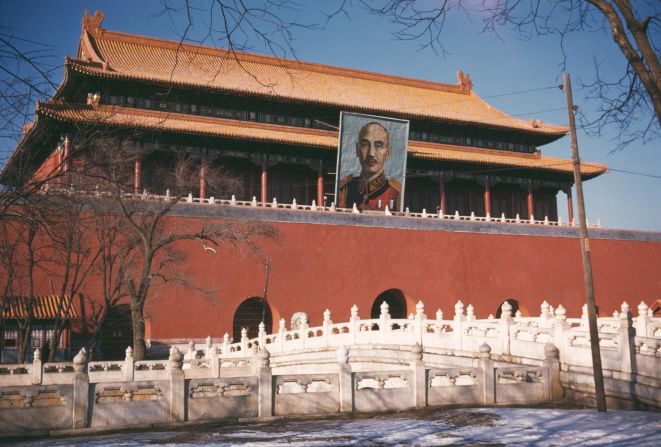

Only six years after the Palace Museum opened, however, the threat posed by Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, to the north of Beijing, meant that many of the Forbidden City’s most valuable treasures had to be removed from the capital. The story of their travels across China, as the ruling Nationalist government searched for safe harbor, is long and tumultuous. In 1948, however, as the Nationalists faced down the prospect of losing the civil war against Mao Zedong’s Communist forces, they shipped over 600,000 of the finest palace treasures to Taiwan, where they remain to this day.

Into the modern age

During the years of Chinese Communist Party rule that followed, threats to the palace came not only from the capital’s aforementioned architectural changes but also the ideological extremism of the Cultural Revolution.

In August of 1966, the first of a series of mass rallies designed to encourage China’s youth to rebel against what Mao termed the “four olds” (old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas) was held in Tiananmen Square, just to the south of the Forbidden City. The palace, hidden behind Tiananmen – which the million-plus students directly faced – seemed to embody the ancient values they were being encouraged to attack. The rallying students began agitating to enter the palace, intent on destruction.

Premier Zhou Enlai, hearing of the threat, issued a directive closing the Forbidden City that night, and sent soldiers to protect it. On returning to find the heavy wooden gates of the palace shut, the Red Guards erected signs reading “Palace of Blood and Tears,” “Burn the Forbidden City to the Ground” and “Trample the Old Palace.” Zhou kept the Forbidden City closed for the next five years, eventually dispatching a garrison of soldiers to live there, such were the constant threats.

The palace would finally reopen in 1971 for the visit of the US table tennis team, whose arrival in Beijing marked the tentative beginnings of a new era in US-China relations in what became known as “ping-pong diplomacy.”

The main threat to the palace today is not fire or conflict, but simple age, coupled with the footfall of millions of visitors who tour the site each year. Palace Museum authorities are faced with ongoing questions about how to best preserve and present the site.

Any ambivalence once felt by China’s communist rulers towards the Forbidden City has now been replaced by an eagerness to emphasize China’s cultural heritage. In a 2014 speech to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which declared the Palace Museum a World Heritage Site in 1987, President Xi Jinping commented that, “A civilization carries on its back the soul of a country or nation. It needs to be passed on from one generation to the next (…) We need to bring all collections in our museums, all heritage structures across our lands and all records in our classics to life.”

Though some renovations can be traced back to preparations for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, changes to the Palace Museum have gathered pace since Xi’s ascendancy, particularly as the palace’s 600th birthday approached. Previously-closed-off areas of the museum have reopened, and visitors can now also walk on top of much of the palace wall. The total open area in the Forbidden City is now up to 80%, compared to only 52% in 2014, with plans to increase to 85% by 2025.

While the palace buildings tended to be sparsely furnished, there has, recently, “been an attempt to recreate the material culture of the spaces,” said Jeremiah Jenne, who leads history programs in Beijing and has written extensively on the Forbidden City, referring to renovations that have seen the halls furnished with period decorations. “For international visitors in particular, this helps them to envisage what these spaces might have looked like when they were actually in use,” he said in an interview.

Questions of authenticity

The challenge of preserving and enhancing the historical integrity of the Forbidden City has seen some of the site’s more modern buildings demolished in pursuit of imperial “authenticity” (a notion that is not without dispute). For those structures that remain, restoration efforts have emphasized traditional construction methods, while incorporating modern fire and earthquake protection.

“Replacing the cracked glazed tiles or refurbishing the eroded plastered columns with new materials prepared in the traditional methods, is widely accepted and practiced,” said Matthew Hu, trustee of the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center, in an interview. “In some ways, practicing and keeping alive this kind of craftsmanship is also a way of preserving the heritage.” The museum has also looked outside China for “help from professional preservation institutions and foundations,” added Hu, by drawing on assistance from international bodies like the World Monument Fund.

In deciding which period of history to evoke, the Palace Museum has tended to opt for the opulent 18th-century style of the Qing dynasty – “an imaginative moment,” the scholar Geremie Barmé has written, “that bespeaks China’s last blossoming as a strong, prosperous and unified empire” before the tumult of the 19th century.

Such choices relate to the wider challenge, identified by Jenne, of deciding “what sort of museum it wants to be.” The Palace Museum holds over a million antiquities, including 367,000 pieces of porcelain and 53,000 paintings, and has staged an increasing number of exhibitions to showcase them. “Does the Palace Museum want to be the Versailles or the Louvre?” Jenne asked. “Does it want to recreate the look and feel of the palace as it was in the Qing dynasty, say, or instead use the palace buildings as halls to display antiquities and treasures?”

The increasing number of exhibitions and events held at the Forbidden City all fit into an attempt to showcase its restored glories for a broader and younger demographic, perhaps further encouraging the “cultural confidence” Xi has spoken of. The Forbidden City’s appeal to this group has been driven by its recent use as a setting for a range of high-profile television dramas (including the wildly popular “Story of Yanxi Palace,” streamed more than 18 billion times in 2018), documentaries and reality shows.

The Palace Museum’s new director, Wang Xudong, has observed the importance of employing new technology to increase the landmark’s profile within China. A recent partnership with Chinese technology giant Tencent to digitize palace treasures and offer immersive virtual reality experiences is part of this approach, as is the museum’s use of social media. “In this fast-developing digital era,” Wang told Chinese state media in 2019, “we need to fully connect technology and excellent traditional Chinese culture.” The strategy certainly seems to be working: Last year, visitor numbers exceeded 19 million, making the palace the most visited museum in the world – with a majority of visitors under the age of 40.

Having endured six centuries of fire and conflict, natural disaster and periodic neglect, the Forbidden City has now been adopted by China’s leaders as a proud symbol of the nation’s history and culture, with money lavished on its restoration and preservation. Its future, for now at least, seems as secure as it has ever been.

Top photo: Aerial photo of the Forbidden City taken in 2008.

Graphics by CNN’s Woojin Lee, Sarah-Grace Mankarious and Marco Chacon