Editor’s Note: Joanna Bourke is a professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London, and the editor of “War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict.” The following is an edited excerpt taken from her introduction. Opinions in this piece belong to the author.

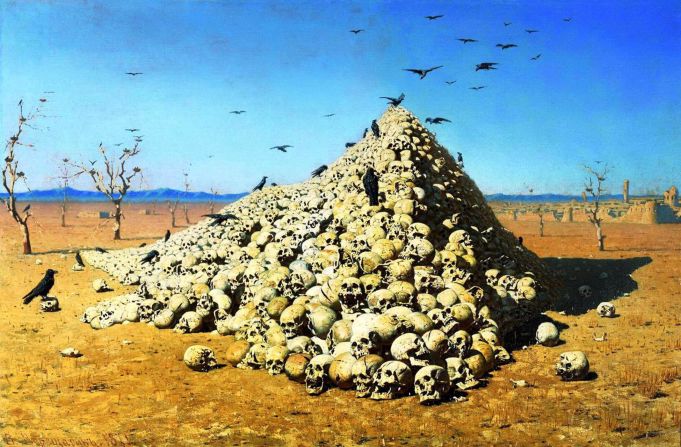

War is the most destructive activity known to humanity. Its purpose is to use violence to compel opponents to submit and surrender. In order to understand it, artists have, throughout history, blended colors, textures and patterns to depict wartime ideologies, practices, values and symbols. Their work investigates not only artistic responses to war, but the meaning of violence itself.

Frontline participants in war have even carved art from the flotsam of battle – bullets, shell casings and bones – often producing unsettling accounts of the calamity that had overwhelmed them. Tools of cruelty have been turned into testaments of compassion and civilians have created art out of rubble.

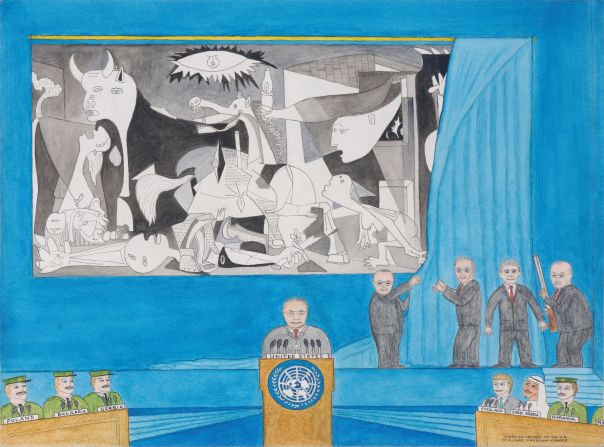

Art, according to Izeta Gradevic, director of Sarajevo-based Obala Art Centre, can be more effective than news reportage in drawing international attention to the plight of ordinary people at war.

“When you face an art form,” she told journalist Julie Lasky, “it is not easy to escape death.”

The art of depicting war

Art in difficult times

The declaration of war typically triggers practical difficulties for artists. At the very least, the sense of crisis risks relegating the arts to a minor role in society.

As Charles C. Ingram, acting president of New York’s National Academy of Design, complained in 1861, the “Great Rebellion” (American Civil War) had “startled society from its propriety, and war and politics now occupy every mind.” He lamented that “no one thinks of the arts” and even artists had set aside “the palette and pencil, to shoulder the musket.”

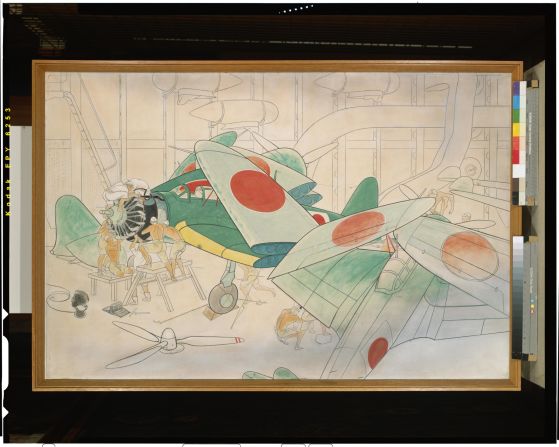

The state appropriation of space sees exhibition possibilities plummeting. Economic sanctions severely limit the availability of supplies. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, for example, Japanese artists faced restrictions not only of paint, but of materials such as silk, gold and mineral pigments that had been used to create “nihonga,” traditional Japanese-style paintings.

But everything from excitable patriotism to down-to-earth curiosity has led millions of artists into the heart of darkness. Some were official appointees, sent by their governments to create a record of what was happening or to offer visual slogans to aid morale. Voluntarily engaging in active war service could allow artists to circumvent some of the restrictions created in wartime. In fact, governments often proved willing to support artists who threw themselves into the war effort.

As the New York literary journal The Knickerbocker extolled at the start of the American Civil War, “ARTISTS! … remember that your elegant brushes are recording the history of a nation.”

This required artists to serve the interests of the collective, however. Many struggled to resolve the tension between artistic freedom and censorship. Was their art supposed to bolster recruitment or demonize the enemy? Were they expected to be “official war artists” (as British artists were called during the First World War) or “official recorders” (as they were renamed during the first Gulf War)?

Even the most message-orientated artist might find that they had little control over the way their images were used. They returned from the front lines to discover that their sketches had been altered or even brazenly distorted by publishers and propagandists.

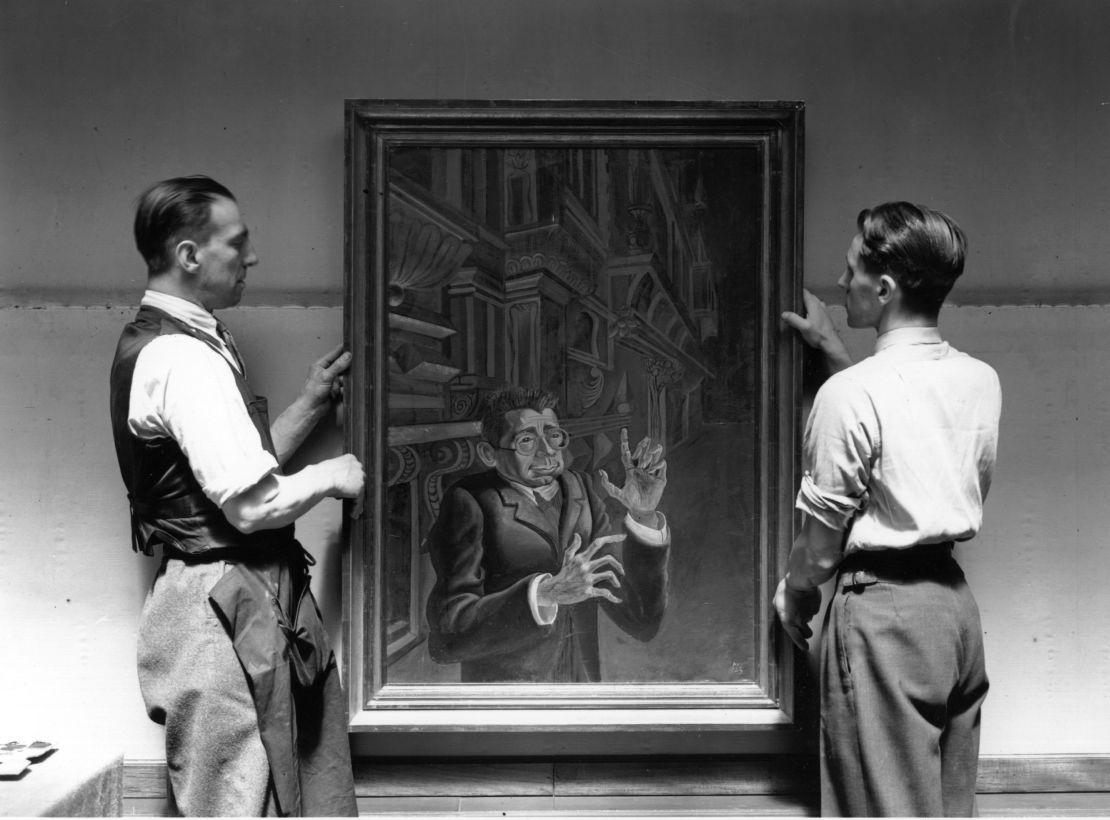

Art as propaganda

Was it the job of artists to reconcile people to war? German artist Otto Dix thought not. His painting “Trench” is a searing indictment of the inhumanity of war, but critics were appalled. In the Kölnische Zeitung, a popular daily newspaper in Cologne, critic Walter Schmits complained that “Trench” weakened “the necessary inner war-readiness of the people” and offered people “no moral or artistic gain.” Museums are “for art … not propaganda,” he insisted.

But many artists embraced their role as propagandists. Miyamoto Saburo’s “Meeting of Generals Yamashita and Percival” is a powerful example. The painting shows negotiations between Japanese and British generals during the surrender in Singapore, one of the most humiliating defeats in the history of the British army. In contrast to the forceful presence of General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the commander of the forces of the British Commonwealth (Lieutenant General Arthur Percival) is portrayed as cowardly and arrogant.

The painting won Japan’s Imperial Art Academy Prize in 1943 but, more importantly, it was hoped that it would bolster morale at a difficult point in the war. The tradition of sensoga (or Japanese war painting) was awkward for those who sought to depict the horrors of conflict. Artists became embroiled in controversy when they exhibited more brutal representations.

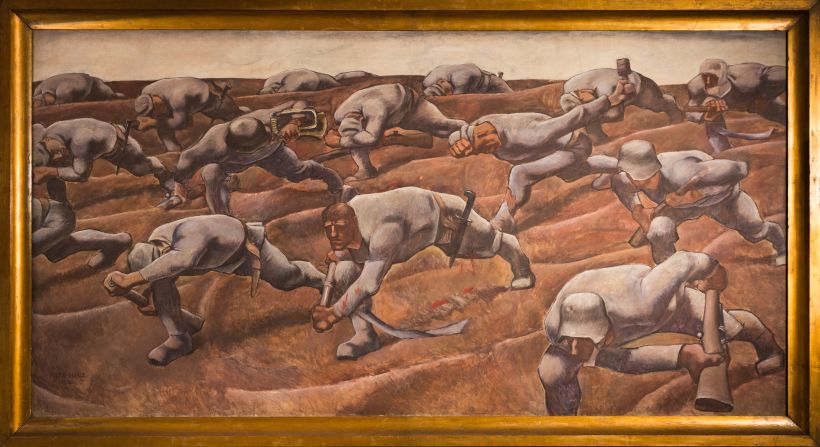

In 1943, for example, Tsuguharu Fujita exhibited “Desperate Struggle of a Unit in New Guinea,” which depicts a fierce battle scene based on the defeat of Captain Yasuda’s troops in 1942. Drawn in muddy browns, there are no clear distinctions between combatants on either side. War hurts. Everyone.

Although military commentators praised the realism of the work, even using it to encourage kamikaze pilots, others were disparaging. Ishii Hakutei, one of the founders of the sosaku hanga (“creative prints”) movement, doubted that the painting would be “useful … in drumming up war spirit.” There was “a danger that the viewer will sense evil before admiring the loyalty and bravery of the imperial troops.”

The realities of war

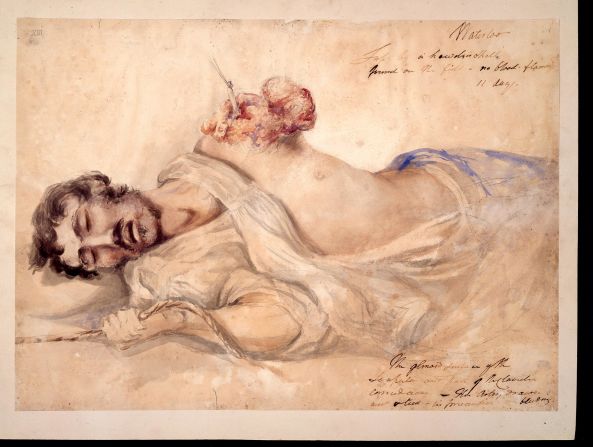

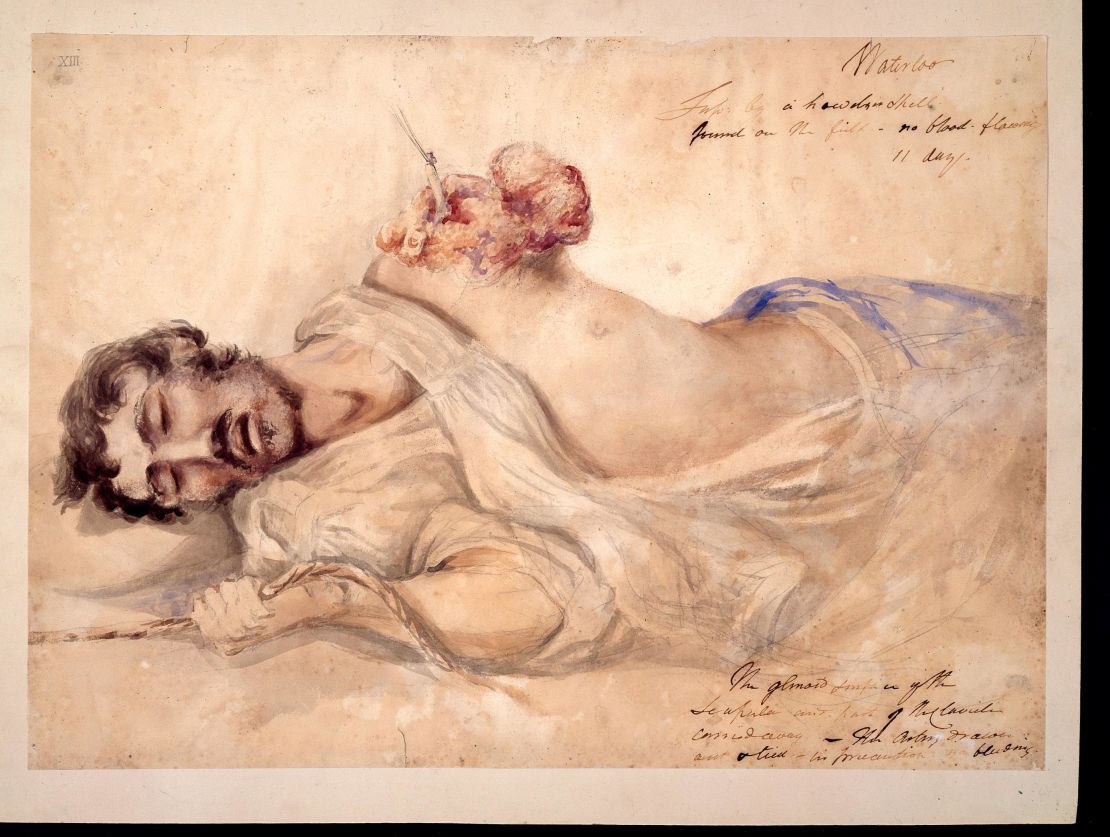

Attempting to capture and convey the visceral horrors of the vulnerable body at war has taken many different forms. It has also been the focus of a very different genre of war art: medical illustration.

Sketches and photography made during conflict have been employed in diagnosing pathologies, aiding surgical practices and assessing the progress of a disease and its treatment. But there is also an artistic tradition in war medicine that emphasizes its artistic merits as much as its medical usefulness.

Its pioneer was Charles Bell, a surgeon, neurologist, anatomist and artist, who in 1815 offered his surgical services to the men who had been wounded during the Battle of Waterloo. One of Bell’s watercolors, for instance, shows a soldier whose arm had been torn off by an exploding shell. His sketches and paintings were intended to illustrate wounds and operative techniques in order to educate other surgeons.

His emphasis on gestures was intended not only to reveal physical suffering, but to excite sympathy in observers. In his words, while the public were viewing the battle at Waterloo in terms of “enterprise and valor,” in his sketches he sought to remind people of “the most shocking sights of woe”

For Bell, visual representations of agony were crucial if the public was to both understand the realities of war and sympathize with its victims. It took great courage, as well as grit, for artists like Bell to look closely at the wounds of war and use their artistic portraits to reflect on violence and corporeality.

Changing attitudes

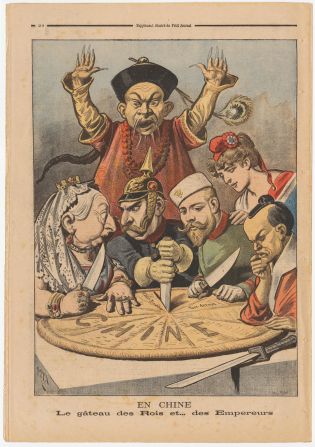

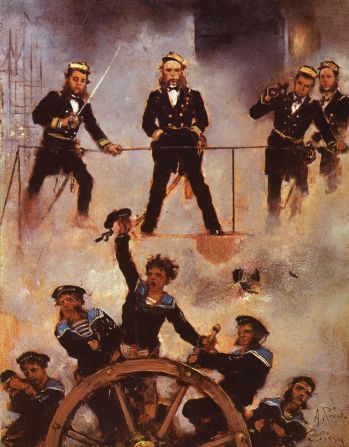

The theme and mood of war art has undergone major shifts over the past two centuries. Prior to the twentieth century, war artists were more likely to depict heroic tales rich in religious imagery, such as the “Massacre of the Innocents” and the “Passion of Christ.” Nineteenth-century British painting reveled in depicting decisive military maneuvers taking place in sumptuous battlefield landscapes.

In France, artists such as Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet, Jacques-Louis David, Auguste Raffet and Antoine-Jean Gros were inspired by the deeds of Bonaparte and his army. Perhaps the most powerful of these is Gros’ “Napoléon on the Battlefield of Eylau,” exhibited at the Salon in 1808. It shows Napoleon visiting the corpse-strewn battlefield in Eylau (eastern Prussia) the day after the bloody French victory over the Prussians.

Tens of thousands of men from both sides had been killed. While Marshal Joachim Murat is portrayed as a callous warrior, Napoleon is depicted as a compassionate, even Christ-like figure, blessing the men on the battlefield.

Even at this stage, though, opposition to the heroic tradition was growing. As the Crimean War dragged on and reports of strategic mistakes proliferated, artists began expressing a general sense of disgruntlement. They began shifting their sympathy away from portraits of great generals.

As with Lady Butler’s art, the true heroes were increasingly the ordinary soldier and his family. Joseph Noel Paton’s “Home” (1856) was an important turning point. Its sentimental depiction of a wounded corporal in the Scots Fusilier Guards returning to his wife and mother proved comforting to a population ravaged by war and anxious about its aftermath.

Paton did not rest content with reassuring representations of the war, however. His “The Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in the Crimea, and staff,” painted a year before “Home,” was damning. It depicted British officer FitzRoy Somerset as Death riding a skeletal horse over the corpses of his own men. Famine, Disease and Death stalk the land.

Admittedly, Paton did not exhibit this sketch at the time. It was first exhibited in 1871, by which time artistic dissent was more established. War artists were turning sour.

Artistic bitterness escalated during World War I. The bloodbath at the Battle of Passchendaele was decisive for young artists such as Paul Nash. In an angry letter to his wife Margaret, he explained that the war was “unspeakable, godless, hopeless.” Its horrors were so great that he no longer considered himself to be “an artist interested and curious,” but was instead a “messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on forever.”

Such artist-messengers, like their counterparts in literature, developed a narrative – what the literary scholar Samuel Hynes called the great “myth of war” – that began with “innocent young men, their heads full of high abstractions like Honor, Glory and England” and ended with disillusionment.

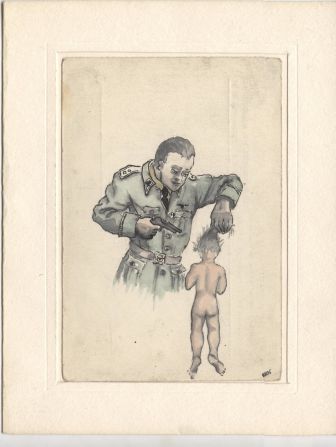

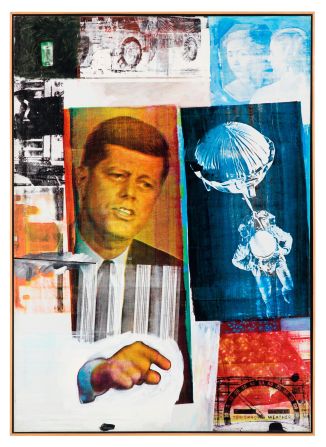

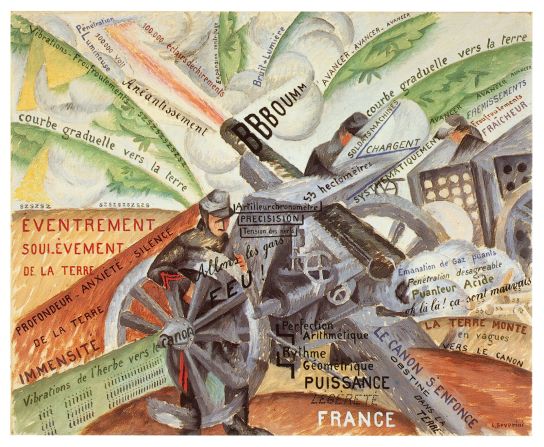

From World War II henceforth, a new, acrid kind of art was required. Representing the “authentic” combat experience entailed assaulting the senses of sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch. It required artists to visually represent the sound of grenades detonating, the stench of high explosives, the metallic taste of blood, and the sight of human bone, muscle, tissue, skin, hair and fat strewn around.

To paraphrase the essayist Elaine Scarry, “to see pain in war art is to have certainty – to see heroics is to have doubt.”

Intrinsically political

Arno Breker, often referred to as “Hitler’s favorite sculptor,” once declared that art “has nothing to do with politics … for good art is above politics.” He was wrong. Art is intrinsically political. It is often explicitly so, most obviously for artists who use their creative talents to protest against warmongering.

It is often explicitly so, most obviously for artists who use their creative talents to protest against warmongering. Even artists who explicitly seek to change the way people understand armed conflict can find that their art actually obfuscates atrocity. Art can turn violence into a tempting melodrama or consumable drama; “war as hell” is beguiling.

But even when not explicitly depicting the human body in its abject or mortal states, war art involves the cultural contemplation of violence. The victors and the defeated, the landscapes in which they moved, and imagined pasts, presents and futures are refracted through the creative energies of artists. The dead also live on in the hand of the artist and the eye of the witness.

Loss is there for all to see. Audiences as well as artists celebrate an aesthetic of responsibility; looking closely rather than looking away.

“War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict,” published by Reaktion Books, is available now.